‘Unlike anything that has ever come to this town’: An oral history of WKU football hosting a Russian semi-pro team for a ‘highly unusual’ week filled with unforeseen high jinks

April 20, 2020

Just 27 years ago, the WKU football program was on the brink of extinction. Long before the Hilltoppers became a consistent winner in the Football Bowl Subdivision or Conference USA, the university’s underperforming football team played as a Division I-AA independent.

The university needed to implement a state-mandated $6.1 million in budget cuts for the 1992-93 fiscal year, and Hilltopper football ended up on the chopping block in April 1992.

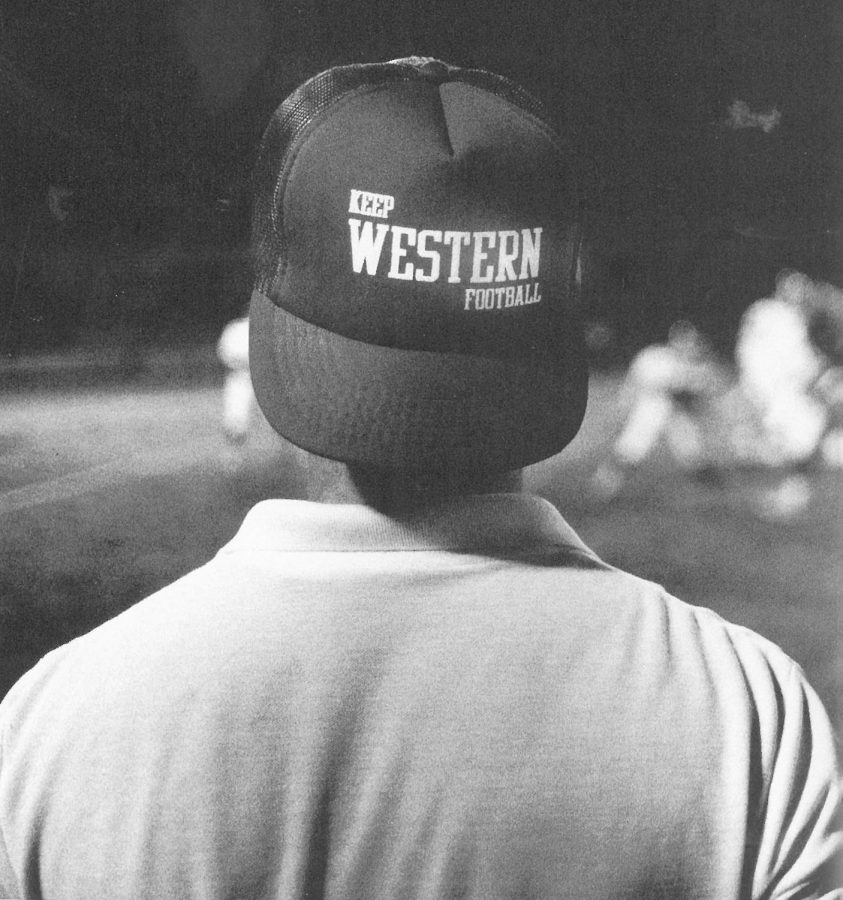

Tensions rose and tempers flared, but a combined last-ditch effort by a vocal collection of program supporters helped WKU football make its most crucial goal-line stand to date.

The Board of Regents approved $6.1 million in cuts on April 30, 1992, but the WKU football team was spared. Although the Hilltoppers dodged elimination, the WKU football program’s annual budget decreased to $450,000, which was about half of the previous year’s funding.

Head coach Jack Harbaugh was faced with several dilemmas — fewer scholarships and less full-time assistant coaches were to be expected, but schools dropping off his team’s 1992 schedule after rumors told them WKU would cut football wasn’t a foreseen consequence.

With the help of athletics director Lou Marciani, the 1992 WKU football team replenished its schedule. By the fall of 1992, the Hilltoppers were locked into a 10-game regular season schedule that featured two open dates very close to one another on Oct. 3 and Oct. 17.

Desperate to drum up any sum of money for the still-ailing football program, the Hilltoppers scheduled an exhibition contest against the Russian Czars — an American-style football outfit featuring alleged Olympians among several other standouts from different sports — on Oct. 17.

Although the contest ended up in the record books as the first time a Russian football team had ever played on a Division I college campus in the United States, the off-the-field antics that filled the week leading up to the showcase overshadowed everything that happened on the gridiron.

The Herald conducted 11 interviews over the course of the Spring 2020 semester, granting many of those who were involved in one of the most unique contests in college football history their first opportunity to recount the days leading up to the spectacle in their own words.

Quotations from archival news articles are also included in this oral history to help fill in the gaps and provide additional context to the thoughts and feelings of those closest to the exhibition.

Background information for this oral history project is presented in italicized type, while direct quotations are presented in normal type. Names are listed with the person’s job title during the 1992 football season.

(Note: Some responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Chapter I: ‘A piece of the puzzle’

The WKU football team posted a combined 5-16 record across the 1990 and 1991 seasons, making the program a prime target when the university needed to implement $6.1 million in state-mandated budget cuts in April 1992. Hilltopper football had been losing games and spending more money than it took in each year, which made the program vulnerable.

Jack Harbaugh (WKU football head coach): “It all started with the meeting with the president in his office in March of the spring previous to that [season], when he told us that he had the votes to drop football, but they weren’t going to vote until the end of April. He suggested that we not go through spring practice because of the risk of injury and those types of things, that there would be no football at Western the next year. Our players voted to go through spring practice.”

Rick Denstorff (WKU football offensive line coach), speaking to the Talisman in 1993: “It was a blessing in disguise. It helped get rid of players who were just going through the motions and opened up opportunities for more team·oriented players.”

Lou Marciani (WKU athletics director): “I don’t remember the exact date, but [then-WKU president Thomas Meredith] called me up to his office and said, ‘Lou, I have bad news for you.’ And I said, ‘What’s the matter, Dr. Meredith?’ He says, ‘The Faculty Senate voted to eliminate football. We’ve got a problem.’ I was stunned. So, at that point I said, ‘Well, can you just give me some time to think this through and what we can do?’ I did not think we didn’t want football on Saturday afternoon or Saturday evening in Bowling Green.”

Joseph Iracane (Former WKU Board of Regents chairman): “During my tenure at Western, there were a lot of financial difficulties and, I can attest to that fact, wanting to try to solve the financial problem by dissolving an athletic program. The budget was always a big to-do. I had a very elementary understanding of the budget and the fact that this is all of the money you have. You can’t make money out of nothing. This is it, so now you’ve got to spend it as wisely as you possibly can. Probably the thing we spent the most time on with the president was developing a budget that was necessary for the interests of the whole university and not a special interest group. We had some interesting debates, some of which were good. Some of them weren’t.”

Arvin Vos (Faculty Senate chairman), speaking to the Talisman in 1992: “I understand no one likes to lose a program. For many years, the football program has been costing the university far more than it brings in. That money should have been used for class.”

Marciani: “It was just a rough time in Frankfort at the time. The funding was cut, and it was a rough time for Kentucky in ‘91, ‘92. We were part of that ‘where do you cut?’ kind of concept, and football was selected.”

Vos, speaking to the Talisman in 1992: “The goal of the Senate was to get the budget in line. We decided we can’t afford the millions, so it would be better to suspend the team.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “The thing about finances really wasn’t the driving thing in it. The driving thing in it was Dr. Meredith had been getting some pressure from the Faculty Senate. That was his carrot. He was going to throw football out of here to try to put himself in good position with the Faculty Senate.”

Marciani: “I could have very easily said to Dr. Meredith, ‘I hear you.’ Because basketball at that time, we were riding real high in the ‘90s, meaning to the point where we were — we’ve always been a basketball school, but we were at a high level at that point. We were kicking butt for a little bit there, and so the basketball people probably didn’t want football. I’m just talking, but they thought the money that we used for football could be going to basketball probably. And that’s not true. So, we had that basketball versus football mentality on campus at that point in time and people thought maybe we’re wasting our time with football.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “That was one of the reasons, too. Drop football when football is not doing well and no one will really care.”

Lee Murray (WKU football running backs coach), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “When I was here in the ‘70s, everyone rooted for everyone else. I’d like to see that again.”

Iracane: “I felt like athletics is an educational classroom. Soccer is not just kicking the ball and running up down the field. It’s a learning experience. You learn how to develop a relationship with people, discipline and how to be on time. There’s just so many things that the programs bring to a young person. I felt like doing away with an athletic program is like doing away with a classroom program that’s — in my mind — very necessary for the success of a young person moving forward into business, industry or whatever they happened to do. To me it wasn’t even a close encounter. I just felt like, ‘How could you do this?’ It’s just not the right thing to do.”

Estill “Eck” Branham (Self-proclaimed “No. 1 fan” of WKU football team), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “I can’t see how in the world they can justify dropping football at Western. It’s part of college to me.”

Marciani: “The first phone call I ever got — because it hit the newspapers, I think — was from Howard Schnellenberger, the football coach at Louisville. He called and said, ‘What’s going on in Bowling Green?’ I said, ‘Coach, we might have to drop football.’”

Harbaugh: “We got support in our community. Jimmy Feix, Butch Gilbert, Mickey Riggs — I call them the three amigos — they rallied support among the former players.”

Marciani: “There’s a lot of people that wanted to save it, and I was right there in the middle of it, obviously, because I believed in saving it. It wasn’t just Lou though. Coach Harbaugh killed himself as well. [Coach Feix], he was heavily involved. The whole booster club. It was an effort by a lot of people that were really Hilltoppers for football. They really, really believed in the history of the game being played at WKU and our tradition.”

Jeff Nations (1993 Talisman sports editor): “Ever watch the opening scenes from ‘The Waterboy’? That was pretty much it. Just complete apathy bordering on hostility to budgeting that program.”

Jimmy Feix (Former WKU athletics director), speaking to the Herald in 2003: “That’s when we started writing and calling for solicitations. We tried to drum up ticket sales. All the politicking was great, but probably the single most critical element was Jack Harbaugh did not leave. He didn’t need this program and those headaches … he dug those heels in and did not leave.”

Harbaugh: “At the end of April, the vote was changed. One vote was changed and we got a chance to keep football, but we lost half of our operating budget, we lost 13 scholarships and we lost two coaches. The thing that we lost equal to that was teams saw the news for one month that we wouldn’t be playing football and canceled games. We were independent at the time, so we weren’t in a conference and we weren’t locked into games. Our athletic director had to go out and find those games. Well, we lost three or four of those games, and at one time we only had like seven, eight games on the schedule. So, we were looking for any possible opportunity to play football and to fill those games.”

Marciani: “They cut the budget on me. We scraped. There’s some games we bought in that ‘92 season. When I say buy, they gave us some guarantees to offset some of the cost. We had the ‘92 season to get on our feet and finance a program the president had been directed to take.”

Those closest to the WKU football program at the time have slightly different recollections of how the game against the Russian Czars came about, but all signs point to Marciani being the one who discovered that a traveling troupe was playing American football across the country.

Jim Clark (WKU coordinator of marketing and promotions): “There was excitement from people who had gone in to keep football, and we just needed to play as close to a full schedule as possible. I think the uncertainty over whether we would have a team made it difficult to schedule that year.”

Paul Just (WKU sports information director): “I don’t remember exactly what all they did to try to fill that date, but it seems like it was something to do with some change that created an opening that wasn’t supposed to be. Lou Marciani did a lot of the football scheduling for Coach Harbaugh and they were wanting to fill that spot so they could play another game because the limit had gone up to 11 games a year by that time.”

Bill “Doc E” Edwards (WKU head athletic trainer): “We didn’t have 11 games on the 1992 schedule, so that’s my understanding of why we did this exhibition game during the season. I think it was Lou’s idea. I think Lou found out about it and it was his idea to use that as a home game to bring in a little more revenue for the program at the time, which seemed kind of strange to everybody that Russia would have any kind of football team, much less play us.”

Just: “Somewhere along the line Lou stumbled across — I’d never heard of it before — a Russian national team in American football, which is not played over there regularly. There were some other teams that they played, I think in Europe and that sort of thing, and they had a little bit of a schedule. They were making a tour of the United States and played like coast to coast.”

Eldon Cunningham (Russian Czars football head coach): “I was searching the NCAA site and saw teams looking for games, so WKU didn’t have a full schedule of games. Contacted Coach Harbaugh, and we made it happen.”

Harbaugh: “We got the information that this team from Moscow was going to tour the United States and they were playing games and they were looking for games.”

Cunningham: “What I was looking for was more to get players experience and let them see what real teams looked like so that they could get a better grasp.”

Just: “What’s obvious since it’s ‘92 is we survived [budget cuts] with football, but we needed all the income we could get. Lou and Jack didn’t want two open dates — they wanted to generate some income. You almost never hear of an exhibition game in football, but they had a date when we had a date. They wanted to play, and [Marciani and Harbaugh] needed every bit of money we could get because we kept football, but we didn’t keep the football budget.”

Marciani: “The whole year was a blur. We struggled so hard and I worked so hard as an athletic director with several people to generate funds so that we could save football. We had to put in some licensing for seats in Diddle Arena, the different levels and the different tiers. It made it pretty painful, and that hurt — hurt in the sense that people were not used to doing that. But it was a base of funding that guaranteed the least the university saw coming forward to support the program at a minimal level as it existed. Even still, we had to scrape here and there.”

Harbaugh: “I don’t know the process or how it all worked out, but we contacted them and the circumstances were that they wanted a place to stay. They wanted housing for a week and they wanted food and that type of thing. A place to practice, use our facilities, which we did. Our athletics director agreed to do that.”

Marciani: “The Russian Czars were a piece of the puzzle to generate dollars and do everything we could to maintain and elevate something — as it has now — for the future of the university.”

Although Oct. 17 was listed as an open date on the schedule included in the 1992 WKU football media guide, the date was later modified to reflect a meeting with the Russians. Team personnel still remember their confusion upon finding out they’d be playing their country’s Cold War rival.

Robert Jackson (WKU football senior wing back): “I thought it was something fun to do but weird at the same time. I didn’t understand the purpose behind it, but I welcomed the challenge of playing against athletes who were semi-pro athletes. I was a 21-year-old kid myself, so I thought it would be a good test for my teammates and I. I felt like this game was being used to curve relations between America and Russia and to bring positive change to the negativity at the time between both countries. To my knowledge, I had never met any Russian people, so I was intrigued to see what they were like and see if they were good football players.”

Mark Quisenberry (WKU football student manager): “We had teams drop off the schedule, so it was just kind of a flash in the pan. ‘Hey, let’s see if this’ll work out.’ It wouldn’t count on our records. Actually, if you look, you can’t find stats or anything on it anywhere. We picked up the game just on a whim. ‘We’ll see what we can do.’ Basically, everybody was going to get to play.”

Harbaugh: “We stumbled into it, and that’s not what we wanted. We would have rather played a normal schedule and the way we had done it before. But my vision was that we could take this and make it a tremendous educational experience for our players. I didn’t know if that would ever happen or if any of our players would interact with them, but that was my hope.”

Cunningham, writing to Bowling Green citizens, WKU students and the university’s faculty and administrators in 1992: “In a time when both American and Russian people reside in peace, it is only fitting that our two teams engage in friendly battle on the playing field. For this I say thank you to all those who are responsible. Thank you for making the world a better place for all of us … this exchange of culture will indeed enrich all of our lives and the lives of all who take part in this great game of American football as it has mine. Just by being associated with the good people at Western Kentucky University and the people of your great city.”

Click the PDF below to scroll through the game’s souvenir program:

Chapter II: ‘We all spoke the language of football’

The Russian Czars limped into Bowling Green on Oct. 12, 1992, fresh off a 35-0 defeat at the hands of Team USA, a U.S. Football Federation squad of semi-pros and amateurs, in Chicago one day before. The Czars were 3-3 after playing all of their first six games on the road, picking up wins over the Belgian National Team, Sweden and Norway by a combined 131-6 margin.

The Czars played their U.S. tour opener on “a crisp October afternoon” just two days after the visitors arrived from Moscow, carrying with them paraphernalia they’d also haul to Kentucky.

Edwards: “Seems like they were here a lot longer than they were, but my recollection is they were here that week prior to the game. They got here maybe Sunday or something like that and we housed ‘em down in [Douglas Keen Hall]. It seemed like a long week in a lot of ways, but I guess that’s all it was.”

Harbaugh: “The week of the game they rolled into town and pulled up the bus at the dormitory, and the interesting thing about that experience as I look back at it, the Iron Curtain had come down in the late ’80s, and they came, really, with wares, if you might. They had cases of vodka that they were peddling. They had former uniforms that the army had just — when the Curtain came down, some of the army just dropped their uniforms in the street and they picked ’em up. ”

Edwards: “They had brought all kinds of Russian memorabilia. Russia still had that Soviet Union emblem, the hammer and sickle. The Soviet Union had been dissolved, but they had a lot of that stuff, and so they were bartering stuff like that and watches and they had a lot of those [Matryoshka dolls]. My understanding is they were trading that for jeans and maybe some tennis shoes and stuff like that. The main barter was vodka, I believe, from what I have been told.”

Just: “I think some of the local clothing stores did real good on their sales of blue jeans. Back then, blue jeans were pretty hard to find in the Eastern Bloc, so to speak. I think everywhere they went, there were guys out spending their money on blue jeans and vodka.”

Edwards: “The guys down at the dorm, that’s a whole ‘nother story, and all I got was just the stories about what was going on down at the dorm. I think every night down at Keen Hall, that was quite an adventure. I think there was a big enlightenment for our guys.”

Just: “I remember a couple of those [Russian players] couldn’t understand why they couldn’t bring their vodka in the room. I mean, vodka is to Russia what beer is to Germany. It’s just a staple. So, that was a little curious. I said, ‘How are we going to have this?’”

The university’s alcohol-loving visitors had a full schedule of events planned, according to a team itinerary published in the Oct. 13, 1992, edition of the Herald. Events for the Russians to participate in during their stay included: a campus tour, a tour of the Corvette Plant, a tour of Mammoth Cave National Park, an Alan Jackson concert in Diddle Arena, a shopping trip to Greenwood Mall, the 10K Classic Road Race and many provided team meals to consume.

Cunningham said events like “the joint team banquet” and other social outings allowed his group of guys to “interact with everybody” and have meaningful dealings with American culture.

Cunningham: “One of the highlights for the players was going to the Corvette Museum, especially since they found out that the Corvette was designed by the head of the Corvette program, [Zora Arkus-Duntov], who was a Russian. So, that gave ‘em a sense of pride.”

Herald sports writer Chris Irvine penned a commentary titled “Czars enjoying same pleasures as Americans” in the Oct. 15, 1992, edition of the Herald.

Irvine wrote about spending a day with two members of the Russian Czars, and his words painted a picture of the Russian players as stereotypical young men interested in “food, clothes, money, alcohol and girls. Mostly the girls.”

Oleg Sapega (Russian Czars football defensive tackle), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “American girls are very friendly and nice … Busch [Beer] is very good.”

Andrew Claffey (Russian Czars football inside linebacker), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “The difference between Russian and American women is their degree of friendliness. Russian women are shy and quiet, while Americans aren’t afraid to come up and introduce themselves and ask questions … [Russians] drink [vodka] like water.”

Quisenberry: “They liked to party and have a good time. The thing was, if you toasted to your family or whatever like that, they continued to toast in enjoyment until you ran out of people to talk about. They were very hospitable and very enjoyable, but they were also very respectful of our culture. And it was cool and interesting for me to sit back and be able to take in the culture from Russia. ‘Cause it was kind of in that transition, Cold War down, and Russia was in a transition period. It was interesting to be able to sit there and listen to ’em talk about — I don’t want to say for things that we took for granted — for being able to walk down the street and go get something to eat or drink or anything like that. It was a different world for them.”

Jackson: “We hung out with them and I thought they were pretty cool to hang with in the dorms and in practice. They asked a lot of questions. One of them even told me he’d never been around black football players before and asked me a lot of questions about my culture. I appreciated him showing an interest in who I was versus stereotyping me based on who he thought I was, which goes on in this country a lot.”

Dan McGrath (WKU football freshman strong safety): “They stayed in the dorms with us, so we spent lots of time that week hanging out with them. They wanted to trade Russian military hats and jackets for blue jeans and tennis shoes. We treated each other like teammates during that week and really enjoyed our time spent with them. Although we did not speak the language, we all spoke the language of football, so there was plenty of bonding through practices.”

Quisenberry: “They didn’t live in the rooms with our players, but there were a bunch of empty rooms around our players. All week long, our guys, when they weren’t in class, spent time with their players. [The Russians] were really soaking in what was being shown to them, and I’m very appreciative. It was interesting to spend some time with them. Just a bunch of great guys.”

Jackson: “I remember them drinking a lot of liquor the week they stayed with us. They wanted to trade items for blue jeans. I don’t think they had many blue jeans in their country. I thought that was hilarious. It’s an experience I will never forget.”

Along with the memories he’s been able to cherish for years since, Quisenberry was able to obtain a piece of headwear that’s stuck in the minds of everyone he encountered in the ‘90s, which was quite a few people since the then-22-year-old “would put in a good 60, 70 hours a week working with the football program” while he finished “undergrad on the feel-good plan.”

Quisenberry: “I actually — up until about three years ago — had an actual Russian babushka type of hat. It was a winter hat that a Russian soldier would wear in the wintertime. One of the players gave it to me, just as a friendly gesture for spending time with him. He said, ‘I want to give you something,’ and he gave me that.”

Harbaugh: “About Tuesday or Wednesday, [Quisenberry] came into the office and he was walking around with this hat like the one George Costanza wore on Seinfeld. He had the high, square fur hat that he had procured. He came in and I said, ‘Where in the hell did you get that?’ He said, ‘I bought it. They sold it to me.’ I said, ‘Get that thing off your head for crying out loud.’“

Edwards: “Mark Quisenberry wore that hat all the time for a couple of years.”

Quisenberry: “I can legitimately say that I was able to walk around in the wintertime with a long-sleeve shirt on and sweatpants ’cause that’s how hot that thing was. I didn’t need a jacket. It was very warm.”

The Russian Czars were coached by 41-year-old Eldon Cunningham, a former quarterback at McNeese State. After a stint coaching high school football in the United States, Cunningham defected to Russia, where he coached the Moscow Bears to the first-ever Super Bowl in that country before he helped establish the Russian Czars football program in January 1992.

Harbaugh: “On Monday, we went out to the practice field and we met the head coach, Eldon Cunningham. He was from Houston, Texas, and he spoke English. He and I communicated, we went out and watched practice. They were hitting dummies, doing different things. We had a nice conversation and they practiced and we practiced.”

Just: “[Cunningham] was a bit of a character. I don’t know how much of what he shared with [Jim Clark] and I [was true]. Jimmy and I were both around him quite a bit, in that week’s time that they came in the week earlier, and worked out every afternoon. He was a bird. I know he told us that his ex wife was the daughter of the former governor of Louisiana. I don’t know if that’s true or not, among some other things, but anyhow.”

Harbaugh: “They practiced in the morning, like 10 o’clock, ’cause they had no classes or anything. So, they would use the morning to practice. They used our fields. They used our dummies and our blocking sleds and all the equipment we had on our practice field. And then we practiced in the afternoon. 4:30, 4 o’clock, our normal practice time.”

Edwards: “Back in those days, we practiced across the railroad tracks, where our track facilities are now. So, that’s where they practiced earlier in the day, and then we practiced later at our normal time. I can remember going over there the first day. I had one of my assistants be there with ‘em while they were practicing in case they needed any help the rest of the week, but I went over there that first day and we put ‘em down at the visiting locker room, down at the other end of the stadium. We were going down there and one thing I remember is that their equipment — their shoulder pads and their helmets and all that — were really inexpensive ones.”

Quisenberry: “Their equipment was outdated, to say the least. It was kind of like they bought it back in the day on what would be [similar to] eBay or whatever. I doubt half of it was certified.”

Edwards: “I remember jokingly saying they looked like they had Little League shoulder pads and stuff to one of those guys. It was low end of the spectrum equipment. The shoulder pads, they were kind of small and probably not big enough for some of the big guys that they had.”

Quisenberry: “Of course, most of those guys, even when they practiced, didn’t have helmets on, I don’t think. ‘Cause most of ’em were rugby guys, so they didn’t believe in it. For them the biggest thing was just getting out and getting exercise and the camaraderie of their comrades.”

Edwards: “My recollection is there were wrestlers on [the Russian team]. I remember seeing a handful of ‘em with cauliflower ears. We had talked about it in my profession, in athletic training all those years, but we didn’t have wrestling at Western. So, I had never seen anybody, really, with it. It was in all our textbooks and we talked about and we had to learn about it, but several of those guys had it. That’s where they get their ears rubbed so much from wrestling and all of that, it bleeds in there and fills up part of the cartilage there, between the skin and the cartilage, it bulges out and looks really awful. I remember several of ‘em having that. Those guys were older, and I don’t know what their age would’ve really been, but they were older. They were speaking Russian and whatever language they were speaking, so that made it interesting.”

Quisenberry: “They would practice during the day while our guys were in class and then they would just come and just watch us practice ’cause they wanted to see how everything was going to play out as far as American football, as they called it. ‘Look at this real American football.’ It was really exciting.”

Just: “There were some Americans on the team, too. It was kind of like most international or pro basketball overseas or whatever. You can have two or three or four non-native players.”

Edwards: “I remember they had a guy that they called their doctor that was with ‘em, and I don’t know if he was a doctor or more like an athletic trainer like myself, but I think he was a doctor. I know that the center for their team, the guy that was from the United States, was talking about how they injected some of their injuries and he wouldn’t let ‘em do it to him because he wasn’t sure if they were using another needle or not and crazy stuff like that. They had a little training kit, and it didn’t have much in it the way I remember it, training kit-wise. I remember us giving [the Czars’ team doctor] a pair of scissors, anyway. We donated a pair of scissors to the cause, but everything was pretty primitive with what they were doing.”

Quisenberry: “Their equipment, I would care to venture, would come nowhere near passing safety. As Doc E. said, it was very suspect, to say the least.”

Harbaugh and many others close to the WKU football team recalled the Russian Czars having an Olympic sprinter on their roster. The roster listed in the game’s souvenir program included a special note beside the entry for No. 24, Vladua Pouzerieav, a 6-foot, 205-pound running back.

The note for Vladua Pouzerieav read, “silver medal, 100 meters, 1988 Olympics.” According to Olympic.org archives, medals for the men’s 100 meters at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, went to Carl Lewis (gold), Linford Christie (silver) and Calvin Smith (bronze).

Several other players listed on the numerical roster for the Russian Czars had special notes beside their entries, but Google searches for their names and/or their accomplishments either resulted in a “did not match any documents” message from the search engine or confirmed people by the names listed had never received any awards, honors or Olympic medals.

Harbaugh: “In watching practice a couple times during the week, these guys were about as impressive a looking team as you’d want to see. I think they had Russian Olympic wrestlers. The middle guard was a big, big man. The running back, I think he finished second in 200 meters in the Olympics — just an outstanding athlete. But they had not played football.”

Cunningham: “The [Russian] minister of sports said that we could go to any venue and pick out any athlete and he would play football. We used wrestlers for linemen, both offensive and defensive. Track and field stars for receivers. My quarterback was a javelin thrower.”

Harbaugh: “I remember going over there, watching practice and marveling at what outstanding athletes they were. Figured we had no chance to win whatsoever. Just no possible way we can beat this team — as coaches do. We go back and tell our players, ‘I’ve watched it. We have no chance. I don’t know why we put this game on the schedule, we have no chance to win.’”

Cunningham: “For me, it was deciding on a roster that I could take with enough players. With the [Moscow] Bears, we had come over to play a game in northern New York and we had 21 players defect to Canada. So, my problem getting another team out to play in the States was political officers out there to make sure that players didn’t defect.”

Harbaugh: “You apologize [to the players]. ‘I apologize to you guys for putting this on the schedule. I had nothing to do with it. It was Dr. Marciani. He put this game down. I don’t know why he did it. We have no chance. Just play as hard as we can and don’t disappoint our fans.’”

Cunningham, speaking to the Associated Press in 1992: “We have NFL size, but not the experience. Nobody understands what they are supposed to be doing, but hey, we’re here to have fun. These players just need a chance.”

McGrath: “We were nervous, but we were excited about playing a team from Russia. Coach Harbaugh sold it to us as we were playing this great group of athletes — most of whom were former Olympic athletes — and he definitely had us nervous to be playing them.”

Much unlike the cash-strapped WKU football program, the Russian Czars were sponsored by Reebok, Pepsi and Miller Brewing Company. During their time in Bowling Green, the tourism commission also recruited local restaurants to feed members of the Russian Czars roster.

Although players weren’t being forced to pay out-of-pocket expenses, the Russians were still becoming unhappy about the quality of food they were being provided. “The entire team is getting sick of the fast food they are being given,” Irvine wrote for the Herald on Oct. 15.

Harbaugh: “On Wednesday, there was a mutiny. The [Russians], they felt they were eating too many McDonald’s and too many Burger Kings and they weren’t eating better food. So, they boycotted. They weren’t going to play. They were going to strike and not play the game.”

Edwards: “We got places to donate food, and I think [the Russians] got some meals out of it. I think they ate a lot of McDonald’s, as Coach Harbaugh tells the story. But the word was they weren’t going to practice. They were getting tired of McDonald’s, probably.”

Claffey, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “We had Burger King for breakfast, Wendy’s for lunch. What’s next, Taco Bell?”

According to the souvenir program for WKU’s exhibition contest against the Russians, the Czars were owned by Harry Rosen. Rosen — 68 years old, as of Sept. 5, 1993 — was a businessman from Las Vegas who took an interest in building relationships within the Russian culture.

The entrepreneur started his football team because Russians love sports and he thought it would be “a great promotional vehicle,” Rosen told News & Record in September 1993.

Harbaugh: “The owner was called in on Wednesday to try to talk ’em into playing the game, and I don’t know how he sweetened the pot to get ‘em to play, but they met on a Wednesday night in one of the classrooms there in the stadium and they decided to play.”

Edwards: “I think [the Russians] got paid to play. I don’t know how much. Probably not a lot, but my story is the owner flew up and either paid ‘em or talked ‘em out of it or something so that they got it worked out where they could go ahead and have that game.”

Harbaugh recalled an example of how concerned most players on the Russian Czars roster were with getting proper compensation for their services — even if that meant giving his daughter Joani the cold shoulder when it came to a potential educational opportunity.

Harbaugh: “My daughter, Joani, she was teaching at one of the northern schools there, an elementary school. She was teaching fourth grade or fifth grade or something like that. She said, ‘Dad, if a couple of those players would come out and kind of talk about Russia and the customs and life in Russia, that might be a tremendous learning experience.’ So, I think it was about Tuesday night or Wednesday, I went to the team — well, I might have gone to Eldon [Cunningham] — but I told them my daughter’s a school teacher and do you think a couple of your players would be willing to come out? And again, this is where my memory fades me. I can’t remember whether he told me or one of the Russian players told me: ‘They go nowhere unless there’s cash.’ So, I did talk a couple of the American players on their team into coming out and they did a fantastic job. I went out with them and the kids were really good and they were really good talking about their experiences in Russia and about the country. So, Joani did get an educational experience, but she didn’t get it from one of the [Russian] players.”

The upcoming exhibition game was already being billed as the International Football Classic, so Harbaugh decided he would partner with Cunningham to take the event to another level.

Harbaugh: “I had this brilliant idea — I mean, brilliant idea. Talked to the staff, I said, ‘You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to have an international practice. We’re going to bring our team out on the field there at Feix Field and we’re going to have our coaches working with their players. Our defensive back coach works with our defensive backs and their defensive backs. We’ll run through drills. They’ll watch, they’ll see football.’ Each and every position coach would do that, and Eldon agreed to do it.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh embellishes the story to no end, but he was saying that this was going to be the United States and Russia coming together on a football practice field, soothing all their wounds about the Cold War and all that. Solving the Cold War here at practice in Bowling Green, Kentucky.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “It was a dog and pony show to try to save football at Western Kentucky. I’m part of this dog and pony show. My entire life is football. I’m here with bells and whistles trying to support it by bringing in all this gimmick stuff.”

Chapter III: ‘Certainly an unusual development’

In an attempt to garner more coverage for the Russian Czars exhibition, WKU invited local and national media outlets to attend a joint practice in L.T. Smith Stadium two days before kickoff. While the media looked on, one of the week’s defining moments went down.

Just: “On Thursday, we had a media day for ’em on the main stadium field. The one we play on now, which was grass at that time.”

Harbaugh: “Practice was about 4 o’clock or 4:30 in the afternoon, and we assembled in Smith Stadium for what I thought would be international diplomacy. We had Paul Just or someone call ABC and they sent a camera man and a gal to the practice and they’re filming. Eldon and I are standing on the 50-yard line admiring our work, what we were doing for the globe, for the world as we see it. He and I were making an impact, and we’re having a little bit of fun in practice.”

Just: “I remember I got sent a message that the writer for the Nashville Tennessean, who I knew real well, was in the office and wanted to know exactly where to go. And [the secretary] said, ‘Can you send somebody to take him over there? I can’t leave.’ She was the only one left in the office ‘cause we were all over there. He was late, so I remember I just hustled back over to the office, which was, at that time, in the marketing area that’s closest to the Downing Center at that end. There were three offices there and then a storage room and a foyer.”

Harbaugh: “At that time, there was no stadium on the other side, just the one side. We were on the sideline looking out into the open field there. All at once, over my left shoulder, I see a car come through the gate down at that end, come on the track and the car is coming down the track and it came to about the 30-yard line, if I remember.”

Edwards: “My remembrance is a sheriff’s car pulled into the gate out there — and that gate’s still there by where the visiting locker room is now on the old side of the stadium there off the Avenue of Champions. It wasn’t quite as big at the time, but there was a gate and a sheriff’s car pulled in there right where our locker room was at the time.”

Harbaugh: “Two or three guys get out of the car and they have long trench coats on. They have ties, they look professional and they’re walking down the track and they catch your eye. I kind of glanced over and, one of ’em said, ‘Eldon Cunningham?’ He said, ‘Well, I’m Eldon Cunningham. I’m the head football coach of the Russian Czars.’ I think he might’ve thought he was going to be interviewed by ’em, but whatever. They go, ‘Well, you’re under arrest, Mr. Cunningham, and we’re going to take you into custody.’ I said, ‘Oh my goodness.’ The ABC camera’s rolling. His response, I’ll never forget his remark. His remark was, ‘How did you find me?’ Which indicated to me whatever they were arresting him for, he understood that this could possibly happen.”

Edwards: “Next thing you know, the coach is heading off in handcuffs in the back of the Sheriff’s car.”

Harbaugh: “They shackled him up, put him in the car, then pulled up to midfield where we were. And he’s in the car and he’s looking out the window and they drive down to the other end. They continue down toward the other end and out they go.”

Just: “I said hello to [Tennessean sports writer Tom Wood] and we talked [in the office] and we kind of turned around and headed back to the stadium. When we got over there. I’m looking for the coach and I don’t see him anywhere.”

Quisenberry: “Like, the police came out on the field, arrested him. It was quite the shock for everybody just sitting there and nobody knew what was going on. They watched the police come take him off and the players were kind of in amazement.”

McGrath: “The funny thing about that was they arrested him right in front of us on the track of the football stadium as we were practicing. I remember several cops in trench coats handcuffing their coach. Coach Harbaugh showed no emotion and kept us practicing. I am sure he was completely shocked like everyone else, but he kept us running our drills as if nothing had happened.”

Just: “They’re going through drills and there’s some people talking to some players and this and that and the other, most of the media people, I knew most all of them then. But I saw one of the student trainers, I said, ‘Well where did their coach go?’ She looked at me kind of funny and she says, ‘Well, he left with the police.’ ‘What?’ And immediately I got busier. I got ahold of several people there to verify what had happened. They said police came out on the field and put him in handcuffs and hauled him off. ‘Oh really? This is certainly an unusual development.’”

Quisenberry: “I remember seeing on the news, them actually showing the police car pulling into the courthouse or the county jail or wherever they would do that and booking him. And you know, we’re kind of looking around and saying, ‘OK, what are we going to do here?’ We still want the game to go on, but obviously they don’t have a coach.”

Unbeknownst to the WKU football program, Cunningham was a man allegedly on the run from law enforcement. He had “been jailed at least twice previously and repeatedly misrepresented his background in sports,” according to a Nov. 1, 1992, Associated Press story.

Cunningham was arrested and held without bond on a fugitive charge for allegedly failing to make more than $15,000 in child support payments. Local authorities made the arrest after they were notified by the Harris County, Texas, sheriff’s office of an open felony warrant issued by the 232nd District Court, according to a news brief in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald.

Cunningham’s arrest made headlines in newspapers nationwide, including the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, News & Record and Deseret News. Interestingly, the headlines Cunningham had already made are what caused him to get caught at WKU.

Harbaugh: “How they found him down there — the week before they played us, they played in Chicago, and on the front page of the Chicago Tribune, they had a little box with a picture on it and then a little tease to what some of the stories were in the paper. I can’t remember whether it was his picture or a team picture, but it was, ‘Russian Czars play game in Chicago.’ And they had his picture in the Chicago Tribune. That big paper somehow got down to Texas — he had left Houston and gone to Russia, but he had a family and child support arrears.”

Just: “[Cunningham] had told us about his wife, and they had a couple of children and she was politically connected, all that stuff. Come to find out, he wasn’t very bright. That team came over from Russia, and he was pictured in news stories. One of the major Washington papers at that time had him pictured on their sports page. He apparently had not just skipped town, he skipped the country to avoid alimony and child support and all that kind of stuff. Some of his wife’s family had seen his picture and not only was it him, his name was on it. Not very smart. Probably taking a chance even coming back into the country. So, he was put in the hoosegow.”

As more details became available, it soon became apparent Cunningham hadn’t shared more than a few details about his past with the WKU football program. According to a November 1992 AP story, he had “abandoned” two former wives, a live-in companion and five total daughters.

The total Cunningham allegedly owed in back support payments rose to at least $35,000, and Debra Worley turned Cunningham in. She alleged Cunningham had fled the country in 1991 and failed to make $15,000 in child support payments to two children he fathered with her.

Debra Worley (Lived with Cunningham in Houston until he deserted her in 1987 while she was pregnant with their second child), speaking to the Associated Press in 1992: “He can start his whole life over just like that … He never paid one payment since he was ordered to pay. Not one payment.”

Cunningham addressed the issue with the Herald, explaining that the Russian government was supposed to be paying his back support payments out of the paychecks he received for being the head coach of the Russian Czars, but there was an issue converting from rubles to dollars.

Cunningham: “My ex-girlfriend was a clerk of the court and we had two children. She was friends with the district attorney, and she made claims in child support on what I owed and so on and so forth and got a felony warrant issued and the warrant was executed.”

The American coach of the Moscow-based team later waived extradition to Texas. Judge Henry Potter ordered Cunningham to be held in the Warren County Regional Jail in the meantime, and the head coach of the Czars would remain incarcerated well beyond game day against WKU.

Cunningham: “Come to find out when we got to Texas — actually, my court-appointed attorney in Bowling Green gave me case law that declared the law unconstitutional … You can’t extradite someone for a civil debt … The back support was eventually paid through the outcome, but it wasn’t nearly as much as she claimed it was. So, I would kind of like to leave it at that.”

According to AP reporting from 1992, “Cunningham has acknowledged that he was wrong for not making payments for the children … ” He declined to comment further on the matter for this piece.

Since the sole coach of the Russian Czars was completely out of the picture, Harbaugh had to make a decision — continue preparations to play the game, or cancel it? Even if everyone was on the same page about trudging ahead, he had to make an executive decision about how.

Harbaugh: “Lou Marciani is in a panic. I mean, he is in a total panic. ‘We can’t play. They don’t have an assistant coach. There was only one coach.’ And he said something like, ‘We got to get them a playbook.’ I said, ‘Nah, they know the plays. We don’t have to do that. What they do need is a head coach.’ So, I’m standing there looking around.”

Edwards: “I guess Lou and them were sweating — Lou was kind of that way anyway — that we weren’t going to have a game, but we had the game. Coach Harbaugh talked Lee Murray and Butch Gilbert, who were two of [former WKU head coach Jimmy] Feix’s full-time assistants back when he was still coaching, into helping him out. Lee was working at the university, but not as a coach, and Butch had retired. But they volunteered to help with the team that year because they were short on coaches with the budget cut and the staff didn’t have many full-time coaches.”

Harbaugh: “I go, ‘Lee, congratulations. You are now the head football coach of the Russian Czars.’ To which he looks at me like, ‘God, a shining moment in my athletic career.’ So, Butch Gilbert was also on Coach Feix’s staff back in the ‘70s and he was our kicking coach. He had been our volunteer kicking coach. So, I said, ‘Butch, I’m assigning you to be the number one assistant for Lee Murray coaching against the Hilltoppers.’”

Just: “When the event was over later that day, Jimmy [Clark] and I got in the car, probably mine, and we went to visit our friend in the jail downtown. By that time, the more subtle heads in the group had gotten together and asked Lee Murray if he could coach the Russian team. I think he said something like, ‘I will if you’ll get me an interpreter.’ So, Lee served as their head coach for that game. I think he still thinks this was quite an accomplishment.”

After Harbaugh helped the Russian Czars find just the right man for their coaching vacancy, he felt an obligation to the team’s players, who had “watched quietly as Cunningham was taken away,” Harbaugh told the Chicago Tribune in an article published on Oct. 16, 1992.

Harbaugh: “Well, you know, I said, ‘I need to do something. The team needs to know what happened.’ I mean, they just watched their coach just get handcuffed and leave the field. So, I called the quarterback, as I recall. I told him, I said, ‘You just saw what happened. They just arrested your coach. It doesn’t look like he’s going to be at the game, but we want to play the game and you know the offense and I’m sure other players know the defense. You can call your offensive and defensive plays, but we want to play the game.’ And he goes, ‘Oh yeah, we want to play. We came to play.’ So, I said, ‘Well, they arrested him.’ He said something like, ‘Well, coach, I’ve been in Russia for a year and a half, two years. Things like that happen over there.’ So the players probably weren’t too concerned by this, because according to him, things like that happened over there — at least that’s the story that I remember. I shouldn’t say he said it. I’m just saying that’s the way I remember it. So, we got that all worked out.”

Chapter IV: ‘I have never seen a man run so fast in my entire life’

After an eventful week full of twists and turns no one could have ever projected, WKU and the Russian Czars were both busy putting the final touches on their respective game plans. The Czars, now led by WKU assistant Lee Murray, had a quick turnaround before game time.

Harbaugh: “Practices were on the other side of the railroad tracks, over there where the track is now. We were separate. We weren’t together for any practice but that joint one.”

Quisenberry: “We would come out of our locker room, walk down the track, walk across and I was kind of the crossing guard to make sure that nobody got hit because you had to go across four lanes of traffic and then make sure you didn’t get hit by the train either. So, you can survive the traffic, but make sure that you didn’t get hit by a train either. We had two practice fields that sat there kind of catty-corner and there was like a 40-foot tall tower that was there that had a rope that I had to pull everything up — camera-wise — for practice.”

McGrath: “Coach Harbaugh was and is an incredible motivator. In typical Coach Harbaugh fashion, he had us ready to compete and we treated them like any other opponent.”

Jackson: “Even though they were semi-pro players, rugby and former Olympians, I felt that we were going to have a pretty good game and we needed to jump out on them early.”

McGrath: “He had us ready to play these great athletes from Russia. He built it up in such a way that we were not only playing for WKU but we were representing our country as well.”

Jackson: “I wanted to show them that USA football was dominant and I wanted to see how good they really were. Some of us aspired to be pro athletes and some of them were supposed to have pro experience, so it was almost like a test of our skills against their skills.”

Murray served as an assistant coach for the WKU football program from 1969 to 1977, but he’d “been working full-time in the property and real estate business, building condominiums and making a successful living for himself” for years before rejoining the coaching staff in 1992.

According to a piece in the Sept. 1, 1992, edition of the Herald, Murray wanted to “bring back a united family atmosphere” to WKU football, and he attempted to do the same with the Czars.

Quisenberry: “Basically [the Russians] needed somebody to manage the game per se so that they could say that they had a coach because [Cunningham] was the only coach that they had. Basically the players did everything else, but [Murray] was very into it. Even though on Thursday he was promoted to an interim head coach for them, he took it seriously. ‘OK guys, what do we need to do to get through this? I’m just here to kind of babysit you all,’ I guess you could say.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh traded Lee to the Russians to be their head coach for the game and I believe they gave Lee a jacket. My memory is that it was kind of a royal blue color, I think that was the color of their uniforms — might have just been white with a little blue on ‘em. But they gave him a Russian Czars team jacket to wear, the way I remember it.”

Jackson: “Coach Murray was my running backs coach at WKU, so it was weird watching him coach for another team.”

Quisenberry: “He was an old ball coach from back in the day. Just a great ol’ guy. I used to sit down and just love to listen to Coach Murray tell stories from back in the day — for basketball and football — because he had a wealth of knowledge and had been around forever.”

Murray, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “I have a great love for this university and the football program. It has been good for me, and I am proud to give something back to it.”

On Saturday, Oct. 17, 1992, game time finally arrived. Kickoff was set for 7 p.m. on a calm, mostly cloudy night with temperatures hovering around 50 degrees. McGrath said he still remembers his first time striking a player that was likely “five to 10 years older” than him.

Unfortunately for the Czars, their football skills were not equal to their athleticism.

McGrath: “I remember blitzing off the edge on the first play of the game. They ran a toss sweep and I met the fullback in the backfield and we had a huge collision, and I thought, ‘Wow, this could be a tough game.’ I later found out that the guy I was battling with all game [Vladua Pouzerieav] was [allegedly] the 100 meter sprint silver medalist in the 1988 Olympics.”

Quisenberry: “It was interesting because our guys, we would talk with each other and half of their guys wouldn’t understand English. We pretty much could say what was going to happen and they wouldn’t know. There were some — obviously the American players — who had a general idea, and they actually had their moments where they played us really tough.”

McGrath: “The fact was, we were much more skilled than them and our schemes were far more advanced. They were strong and fast, but they were behind in terms of football IQ.”

Harbaugh: “One play that I remember is they were punting from like their 15-yard line and they snapped the ball back to the punter and he took an extra step — a step, step and he took like a third and a half step. Well, the personal protector had backed up to protect and he backed right into the kicker and he kicked him right in the back — the lower part of his back — and the ball just dropped. I can’t remember whether it dropped in the end zone for a touchdown, but it was an easy score. When they blocked their own punt, I said, ‘Well, maybe we got a chance here.’”

Quisenberry: “They were wearing down, and we just continued to run the ball. Didn’t throw it very much. Of course, back then with Coach Harbaugh and the flexbone offense we ran, if you threw it five times in a game that was like throwing the equivalent of probably like 25 or 30 times nowadays. ‘Cause his idea of a pass was to run the ball on the edge and see if you could catch ’em ’cause we had some really, really quick quarterbacks and they were good athletes.”

Jackson: “Our defense was playing lights out, and our offense was moving the ball up and down the football field at will.”

The official stat sheet for the game shows the Hilltoppers built a 38-0 advantage to open the exhibition contest, but a Russian player listed as “Zwizna” — likely No. 22 Edward Zwisena, a 6-foot-2-inch, 225-pound running back for the Czars — was able to mount a memorable response for his squad when the game clock read 6:55 in the second period of action.

Harbaugh: “There’s an interesting play that took place in the first half. We kicked the ball off to them and this guy, number [22], he gets the ball on about the 15-yard line. I can remember it today like it happened yesterday. He caught the ball on the 15-yard line. He came down our sideline. I have never seen a man run so fast in my entire life. Whoosh! He went right by our sideline — oh my goodness — and scored. I mean, he took it 85 yards for a touchdown.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh likes to tell that on our special teams coordinator — that he let the Russians’ exhibition team run the kickoff back against us. So, that didn’t go over too well.”

Harbaugh: “Our kickoff coverage team had not been very good all year. We gave up a lot of big runs, returns on kickoffs and it just wasn’t good. As I watched him go for the touchdown — as a coach, you know — I said, ‘Give me the phone.’ I took the phone, and I said, ‘Get me the coach that’s in charge for the kickoff return. Put him on the phone.’ [The person on the other end] said, ‘He’s right here, coach.’ The [special teams coach] got on the phone and I said to him, ‘Listen, I knew going into the game that we were the worst kickoff coverage team in the United States of America. Now, listen to me, I knew we were the worst, but you have just taken our kickoff return team international. We are now the worst team internationally in the kickoff return.’”

McGrath: “The game ended up being lopsided, but I do remember our fans cheering so loudly because one of their [running backs] broke free on a kickoff return and scored. Our fans were so happy for the Russians because the game was getting out of hand.”

Jackson returned two kickoffs during the exhibition game, but he still vividly remembers his return after the Czars scored for the first time. Although WKU had “pretty much ran away with the game in every phase,” he still “felt embarrassed” the Russians scored on a kick return.

Jackson: “Their sideline was going crazy after the score … I was about to go into the game to return a kickoff after their score and I remember Coach Harbaugh grabbing my face mask and telling me to take it to the house. Meaning, ‘Score a touchdown.’ I went into the game and did just that. I returned that kickoff [93] yards for a touchdown.”

Jackson’s 93-yard kickoff return touchdown made the score 45-7 in the first half, and it became exceedingly clear that the Russian Czars simply couldn’t keep pace with the Hilltoppers.

Quisenberry: “I would say about halfway through the second quarter, they started to wear out a little bit and get tired because they weren’t used to the grind. Some of those guys played rugby, so they weren’t used to actually having pads on and being pounded on the whole time. Their conditioning wasn’t the same as our conditioning. Their idea of conditioning was to run a little bit, practice for 30 minutes, ‘OK. We’re good. Let’s take a smoke break,’ sit back and relax.”

Jackson: “We seemed to be much faster and more dominant the day we played them. It felt like the whole world was watching us. I remember being on the field with them and feeling like we were playing the Russians. It was surreal to me. I told my Mom and she was in disbelief.”

Just: “Most of their players had never played before they started putting this team together a year earlier or two years or whatever, and it showed. The quarterback was an American player, but he had played and then had a chance to play [in Russia] and he went. He wasn’t a bad player. It was an interesting game to watch — interesting because of the novelty of it, not necessarily interesting because of what a great matchup it was.”

Harbaugh: “After we went in and we had scored 40-some points in the first half, then we had a running clock in the second half — we ran it.”

Quisenberry: “Eventually we wore ’em down, and Coach Harbaugh wasn’t the type of guy that wanted to embarrass anybody. He wanted to get out there, not get anybody hurt, not embarrass anybody and gain extra reps for everybody. With our offense being a running offense by nature, I don’t want to say he called off the dogs, but he slowed it down. For us, the purpose was to work on what we hadn’t been doing good in the previous games and get ready for our next opponent. It was kind of another practice or scrimmage for us. It allowed the guys to get out there and hit on somebody else without hitting on their teammates.”

Harbaugh: “It was obvious that [the Russians] weren’t technically aware of our game, but they were great athletes. Big, strong athletes. So, it was an interesting experience watching these guys and kind of visualizing what they were in their particular sport and how nationally known they were in Russia because of their international experience.”

Just: “That was certainly one of the most interesting games [Harbaugh] ever coached.”

Claffey, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “You have to look at the fact that these guys have only been playing organized football for about two years. Despite the mistakes, the team can only get better. It is by far the best team in Europe.”

Despite the Russian Czars playing poorly under his guidance and a language barrier to boot, Murray still found a way to have a good time while coaching his very own band of misfit toys.

Quisenberry: “[Murray] had a great time. There was some jocularity, as it goes, during the game. Waving, ‘I know what you’re doing over there,’ and, ‘We know what’s coming,’ and just having a good time about it. He did a great job of keeping them in check and just managing the fact of, ‘You look tired. OK, you go in. I don’t know what your plays are, so you call your plays, but I’ll help make sure that the guys get subbed in if somebody looks tired or if somebody is injured, we’ll make sure that somebody is taken care of.’”

Murray, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “If [the Czars] had a year of real good coaching, they’d be a heck of a football team.”

WKU didn’t score after halftime, while the Russian Czars scored just once in the second half on a 1-yard rush from Zwisena with 40 seconds left in the final quarter. The final score ended up being 45-14, and Harbaugh quickly set out to find a particular player once the clock expired.

Harbaugh: “The game is over, and my mind is racing about what I had just seen — that guy running down the sideline. So, I’m looking around, looking for him and I look and I’m going through guys and I’m congratulating players, but I’m not really focused on congratulations. I’m looking for a number and somebody that I can look in the eye, right? So, finally I find him and he doesn’t speak English and I’m trying to tell him, ‘Have you ever gone to college and have you ever been enrolled in college?’ My thought was that if he hadn’t been enrolled in college, I was going to offer him a full scholarship. He was like, at that time, 26, 27 years old, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘We get him over here around our game for a year or two, I mean, this could really be something.’ Because he’d be like a pro and we’d get him for four years. [College players] didn’t come out early and all that stuff, so I thought we had a gold mine. Evidently, our languages, we didn’t connect, or he had played in college, I don’t remember exactly what it was. But that never came to being, and so that was one of the big disappointments.”

Click the PDF below to scroll through the game’s official statistics:

The Hilltoppers didn’t disappoint on the gridiron, putting on a high-scoring display against the Russian Czars. But the game’s reported attendance of 3,495 people failed to meet even the most modest benchmarks the WKU athletic department had set for the fundraising contest.

Clark said he and Just worked together throughout the week to get eyes on the exhibition game, which paid off when WKU and the Russian Czars were actually mentioned on ABC broadcasts, including a marquee college football game that kicked off at 2:30 p.m. on the day of the game.

Clark: “[Marketing the game] was just the novelty, I guess. We did, from a publicity standpoint, which was more of a Paul Just thing, have some national media coverage of the week.”

Chris Poynter (Herald special projects editor), writing for the Herald in 1992: “It was halftime of the Tennessee-Alabama game [on Oct. 17, 1992] when ABC sportscaster John Saunders looked into the camera and told a national audience that a university in Bowling Green, Ky., had found an innovative way to raise money for its financially ailing football program. Saunders then led into a five-minute piece about Western and its plight to generate dollars for football by playing the Russian Czars, billing it as ‘the International Football Classic.’ Little did Saunders know that the Hilltopper-Czars game wouldn’t live up to its expectations.”

Harbaugh: “ABC used to have that Wide World of Sports. They played that tape with that gal talking about it — ‘We’re here at Western Kentucky University’ — and they had the car driving out of the stadium with [Cunningham] in it after they arrested him. We made national news. It didn’t blow up our crowd any, though. We didn’t get any more people there.”

According to a front-page story included in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald, Marciani “had hoped [the exhibition game] would attract 6,000 people and raise $30,000.”

Instead, the university’s football program earned around $7,700. About 1,500 customers bought tickets, according to an editorial included in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald. “Parking fees and concessions” aided net profits after the Czars were paid their $5,000 guarantee.

Just: “It seems like we drew a reasonable crowd, but wasn’t at all what we’d hoped. At that time, the stadium seated 17,500. We were hoping the novelty of it would fill it up. I don’t know whether it may have helped attendance with all this that went on around it in the closing days.”

Edwards: “We had a pretty good crowd. Not a normal crowd the way I remember it, but still a pretty decent crowd, which helped the budget, I’m sure. Somewhat anyway.”

Marciani: “Attendance was mediocre, but I think we raised something. It was not what we wanted to, if I remember, but we filled the date and brought attention to the football program and to the dilemma we had at that point, and that was, ‘Can we save football?’”

According to the Herald in 1992, “Marciani downplayed the attendance figure, saying that the cultural experience and the exposure on national television was enough to merit the game.”

Marciani, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “Everything can’t be counted in terms of dollars every time you do something. You always want more people to attend, but at least we made money … You take the net and run with it. I’m satisfied with the $7,000.”

Marciani and Harbaugh believed “the game was useful for the interaction of American culture with Russian culture,” and the two both insisted to local news outlets that “all [students] had to do was call the office” if they wanted to participate in the football team’s “cultural exchange.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “If the university didn’t take advantage of it, that’s its fault … If Joe Smith didn’t take advantage, I blame Joe Smith.”

Maggie Miller (WKU sophomore from Cleveland), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “More people should have turned out. These are the Russians, and they are playing football with us.”

Harbaugh jokingly said he harbors another bit of disappointment about the Russian Czars game, especially since the contest’s final score was a notch in the win column for WKU.

Harbaugh: “Paul [Just] and I had this discussion after the game was over. Coaches, we worry about our win-loss record, right? I said, ‘Certainly this is going to go into the win column.’ He goes, ‘No, it’s an exhibition game.’ I said, ‘What do you mean exhibition game? It ain’t no exhibition game. Stick it on my record.’ And I will report, it is not on my record. So, some disappointment came from the game from a selfish personal standpoint.”

Chapter V: ‘It would make a great movie’

Quisenberry remembers the Russian Czars “didn’t want to leave” Bowling Green after the game was over because the players on the team’s roster “were really looking forward to taking full advantage of what was going on in the United States.” He said he will never forget the week the Russians spent at WKU, and everything the Czars did for Quisenberry didn’t go unnoticed.

Quisenberry: “The biggest thing was it was cool to be able to meet somebody from a country that was supposed to be like the bad guy of the world and just kind of learn that, you know what, they’re not as bad as everybody put ’em out to be. They’re just like I am. As Woody Hayes used to say, they get up and put their pants on just the same way we do — one leg at a time. It was interesting to learn their culture and see how it was because for them, we were all friends for life. They might not ever see us again, but we were friends for life. That Saturday night, ‘I love you comrade. You’re my friend for life. If you ever come to Russia, look me up. I will take care of you.’ And that was the cool thing. I’ve never been there before or since, but I felt like I was part of their country for the five or six days that they were there. And the fact of they treated me just like their brother, you know? We were all one of them and to them, we were all one big family. It was cool and interesting to be able to take in that culture for a short amount of time. They went as much as they could, as far as like, ‘This is what was like, this is what it is now and we’re moving forward.’ It was a chance to basically learn a lifetime of history in five days about a country that all you ever heard about was how bad the country was.”

The Russian Czars departed for Chicago at 9:30 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 18, 1992, and returned to Russia shortly after, according to a report inside the Oct. 13, 1992, edition of the Herald.

According to an October 1992 AP article, the Czars were slated to finish their tour in December 1992 at the “first international football tournament.” Just said he didn’t “have a clue where they went or what happened to them after their visit here,” but he and Harbaugh knew one thing for certain as the rollercoaster week drew to a close: “[Cunningham] wasn’t gonna go with ’em.”

At the time, Harbaugh’s office featured a whiteboard he would often write on with dry erase markers. While inspecting his notes and beginning the necessary prep work for his team’s Homecoming game against Central Florida on Oct. 24, 1992, Harbaugh’s phone rang.

Harbaugh: “Sunday morning, I’m sitting in the office looking at the film and just reminiscing about the whole week and the phone rings and it’s Eldon on the phone. He goes, ‘Coach, I guess our guys played pretty well, huh?’ I said, ‘Well, I think it ended up like 45 to 14 and we played every guy on our team and we had a running clock in the second half. But you scored two touchdowns, the kickoff return and you got the last touchdown of the game. The guys really played hard, and you had some great athletes.’ He said, ‘I’m really happy about that. Do you think you could send the film down to Warren County Correctional Institution?’ I go, ‘I can send the film down, but I really don’t have a projector we can get to you so you can watch the film.’”

Following the Russian Czars exhibition, the Hilltoppers went on to post their best performance of the 1992 season, defeating nationally-ranked UCF 50-36 for their second win of the season. WKU stumbled down the stretch, finishing 4-6 after a 47-15 win over Murray State in its finale.

Money issues continued to plague WKU football, which posted losing seasons during two out of its next three campaigns. Program legend Willie Taggart led the Hilltoppers to a 7-4 mark during the 1996 season, sparking a streak of winning seasons that lasted until the 2008 campaign.

Since the university decided to preserve football in 1992, WKU has won numerous conference titles, won a Division I-AA National Championship, transitioned to FBS and posted a 4-2 record in FBS bowl games, finished with a No. 24 ranking in a final AP poll and built an entirely new half of Houchens-Smith Stadium, as the program’s renovated home field is now known.

Iracane and Marciani were both part of “a concerted effort to keep a piece of [the university’s] tradition alive” in 1992, and the two of them look back fondly on their decisions, even if some of “what [they] had to do wasn’t very popular” with other on-campus entities, especially initially.

Marciani: “When you look at the NCAA, they don’t like it when a school drops football. They don’t like it at all. I always told Dr. Meredith, [dropping football] might affect what conference we go to in the future. But he knew. He came from Ole Miss. I was never selling Dr. Meredith. He was always sold on keeping football despite the pressure of the Faculty Senate.”

Iracane: “I was the deciding vote [when the Board of Regents voted on the football program’s fate in 1992.] I voted to keep football, and that’s how it stayed. As it turned out Jack Harbaugh won a national championship in 2002. Obviously after that the football program took off and even much more success, a lot more success moving forward, and the rest is history.”

Marciani: “I knew football would determine what conference WKU would be in today and what conference the school could eventually go to. Without football, I think it would have been a very difficult movement for a proper conference, and here you are today — in Conference USA.”

Iracane: “I think any university would be different [if its football program was abolished]. There are several universities that do away with some athletic programs, and they bring them back. I also think athletic programs are a great supporter for raising revenue. A lot of alumni, that’s a big drawing point for alumni, and whenever you have a successful program, the giving rises.”

Marciani: “That decision [to fund the football program “no matter what it took”] probably cost me a job at WKU because those decisions I made were not very popular, and Dr. Meredith knew that. It was worth the amount of energy that I put into it because you look at the program today and what it means — the university is completely different. It’s really, really different. They have done a great job in elevating that program to a very nice level right now.”

Iracane: “Well, [Jack Harbaugh and I] hugged and kissed [after football was saved]. They had a ceremony after they named the [stadium club] after him and he called me and invited me back. We all went out there together and everybody took a bow because they built that beautiful stadium. What a waste that would have been if we didn’t continue to play football.”

Clark arrived at WKU as an intern in August 1991 and was selected to fill the vacant position of coordinator of marketing and promotion in the athletic department in August 1992. He left the Hill from 1993-2000 to serve as the development associate at the University of Mississippi.

Since returning to the Hilltoppers’ athletic department in 2000, Clark has remained at WKU. Clark said the difference in culture between his first stint at WKU and now is striking.

Clark: “From a facilities standpoint to community support it’s light years ahead of where we were at that time. Just the community, the university, everything has gotten behind WKU Athletics. It’s almost like a totally different place.”

While reflecting on the events of 27 years ago, Cunningham said he wanted to focus on “the team and the kids and the game” — the three aspects he wanted to focus on back in 1992.

Cunningham: “The good part was it was a great experience for the kids. They got to see firsthand what real football was about. In the early days in Europe it was never consistent as far as referees and umpires and so on and so forth. The thing about going to Russia is we literally had to teach umpires, our referees. It was a start-to-finish type thing. Heck, I even had to come up with cheers for the cheerleaders, which was a novel concept for ‘em — for me too. But the kids got to see and play in the States and it was just an overall — except for my moment — great experience for everybody, and that’s what it was about.”

Those who experienced the so-called “Battle of the Big Reds” — as the Fall 1992 edition of The Honorable Mention newsletter dubbed the exhibition — firsthand said they will never forget the contest, especially since it was a part of the 1992 season that set WKU up for future success.

Harbaugh: “Well, a lot of fantastic things have happened in my coaching career, but that experience with the Russian Czars, that was one of the amazing experiences.”

Marciani: “It was a blip in the history of the school, and we turned it from a blip to a plus-plus. I think you learn from history, and you get better at it when you go through these experiences. My fondest thoughts are that every effort by many people to maintain football at Western Kentucky was worth every ounce of energy so that students can enjoy it today, and also the athletes, the state and the region. I’m proud to say that even though I went through a little bit personally, I enjoyed my stay. It was an honor for me to serve the Hilltoppers, no question about it.”