East vs. West(ern) Oral History Project — Part 2: A shocking arrest on the practice field, a lopsided game, reflections on a ‘highly unusual’ week full of high jinks on the Hill

April 18, 2020

Editor’s note: This is Part Two of the Herald’s exclusive oral history project on the unique exhibition game the WKU football program played against the Russian Czars, a semi-pro football team with a roster stocked by standout athletes from other sports, on Oct. 17, 1992. To read Part One of the series, click here.

Chapter III: ‘Certainly an unusual development’

In an attempt to garner more coverage for the Russian Czars exhibition, WKU invited local and national media outlets to attend a joint practice in L.T. Smith Stadium two days before kickoff. While the media looked on, one of the week’s defining moments went down.

Just: “On Thursday, we had a media day for ’em on the main stadium field. The one we play on now, which was grass at that time.”

Harbaugh: “Practice was about 4 o’clock or 4:30 in the afternoon, and we assembled in Smith Stadium for what I thought would be international diplomacy. We had Paul Just or someone call ABC and they sent a camera man and a gal to the practice and they’re filming. Eldon and I are standing on the 50-yard line admiring our work, what we were doing for the globe, for the world as we see it. He and I were making an impact, and we’re having a little bit of fun in practice.”

Just: “I remember I got sent a message that the writer for the Nashville Tennessean, who I knew real well, was in the office and wanted to know exactly where to go. And [the secretary] said, ‘Can you send somebody to take him over there? I can’t leave.’ She was the only one left in the office ‘cause we were all over there. He was late, so I remember I just hustled back over to the office, which was, at that time, in the marketing area that’s closest to the Downing Center at that end. There were three offices there and then a storage room and a foyer.”

Harbaugh: “At that time, there was no stadium on the other side, just the one side. We were on the sideline looking out into the open field there. All at once, over my left shoulder, I see a car come through the gate down at that end, come on the track and the car is coming down the track and it came to about the 30-yard line, if I remember.”

Edwards: “My remembrance is a sheriff’s car pulled into the gate out there — and that gate’s still there by where the visiting locker room is now on the old side of the stadium there off the Avenue of Champions. It wasn’t quite as big at the time, but there was a gate and a sheriff’s car pulled in there right where our locker room was at the time.”

Harbaugh: “Two or three guys get out of the car and they have long trench coats on. They have ties, they look professional and they’re walking down the track and they catch your eye. I kind of glanced over and, one of ’em said, ‘Eldon Cunningham?’ He said, ‘Well, I’m Eldon Cunningham. I’m the head football coach of the Russian Czars.’ I think he might’ve thought he was going to be interviewed by ’em, but whatever. They go, ‘Well, you’re under arrest, Mr. Cunningham, and we’re going to take you into custody.’ I said, ‘Oh my goodness.’ The ABC camera’s rolling. His response, I’ll never forget his remark. His remark was, ‘How did you find me?’ Which indicated to me whatever they were arresting him for, he understood that this could possibly happen.”

Edwards: “Next thing you know, the coach is heading off in handcuffs in the back of the Sheriff’s car.”

Harbaugh: “They shackled him up, put him in the car, then pulled up to midfield where we were. And he’s in the car and he’s looking out the window and they drive down to the other end. They continue down toward the other end and out they go.”

Just: “I said hello to [Tennessean sports writer Tom Wood] and we talked [in the office] and we kind of turned around and headed back to the stadium. When we got over there. I’m looking for the coach and I don’t see him anywhere.”

Quisenberry: “Like, the police came out on the field, arrested him. It was quite the shock for everybody just sitting there and nobody knew what was going on. They watched the police come take him off and the players were kind of in amazement.”

McGrath: “The funny thing about that was they arrested him right in front of us on the track of the football stadium as we were practicing. I remember several cops in trench coats handcuffing their coach. Coach Harbaugh showed no emotion and kept us practicing. I am sure he was completely shocked like everyone else, but he kept us running our drills as if nothing had happened.”

Just: “They’re going through drills and there’s some people talking to some players and this and that and the other, most of the media people, I knew most all of them then. But I saw one of the student trainers, I said, ‘Well where did their coach go?’ She looked at me kind of funny and she says, ‘Well, he left with the police.’ ‘What?’ And immediately I got busier. I got ahold of several people there to verify what had happened. They said police came out on the field and put him in handcuffs and hauled him off. ‘Oh really? This is certainly an unusual development.’”

Quisenberry: “I remember seeing on the news, them actually showing the police car pulling into the courthouse or the county jail or wherever they would do that and booking him. And you know, we’re kind of looking around and saying, ‘OK, what are we going to do here?’ We still want the game to go on, but obviously they don’t have a coach.”

Unbeknownst to the WKU football program, Cunningham was a man allegedly on the run from law enforcement. He had “been jailed at least twice previously and repeatedly misrepresented his background in sports,” according to a Nov. 1, 1992, Associated Press story.

Cunningham was arrested and held without bond on a fugitive charge for allegedly failing to make more than $15,000 in child support payments. Local authorities made the arrest after they were notified by the Harris County, Texas, sheriff’s office of an open felony warrant issued by the 232nd District Court, according to a news brief in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald.

Cunningham’s arrest made headlines in newspapers nationwide, including the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, News & Record and Deseret News. Interestingly, the headlines Cunningham had already made are what caused him to get caught at WKU.

Harbaugh: “How they found him down there — the week before they played us, they played in Chicago, and on the front page of the Chicago Tribune, they had a little box with a picture on it and then a little tease to what some of the stories were in the paper. I can’t remember whether it was his picture or a team picture, but it was, ‘Russian Czars play game in Chicago.’ And they had his picture in the Chicago Tribune. That big paper somehow got down to Texas — he had left Houston and gone to Russia, but he had a family and child support arrears.”

Just: “[Cunningham] had told us about his wife, and they had a couple of children and she was politically connected, all that stuff. Come to find out, he wasn’t very bright. That team came over from Russia, and he was pictured in news stories. One of the major Washington papers at that time had him pictured on their sports page. He apparently had not just skipped town, he skipped the country to avoid alimony and child support and all that kind of stuff. Some of his wife’s family had seen his picture and not only was it him, his name was on it. Not very smart. Probably taking a chance even coming back into the country. So, he was put in the hoosegow.”

As more details became available, it soon became apparent Cunningham hadn’t shared more than a few details about his past with the WKU football program. According to a November 1992 AP story, he had “abandoned” two former wives, a live-in companion and five total daughters.

The total Cunningham allegedly owed in back support payments rose to at least $35,000, and Debra Worley turned Cunningham in. She alleged Cunningham had fled the country in 1991 and failed to make $15,000 in child support payments to two children he fathered with her.

Debra Worley (Lived with Cunningham in Houston until he deserted her in 1987 while she was pregnant with their second child), speaking to the Associated Press in 1992: “He can start his whole life over just like that … He never paid one payment since he was ordered to pay. Not one payment.”

Cunningham addressed the issue with the Herald, explaining that the Russian government was supposed to be paying his back support payments out of the paychecks he received for being the head coach of the Russian Czars, but there was an issue converting from rubles to dollars.

Cunningham: “My ex-girlfriend was a clerk of the court and we had two children. She was friends with the district attorney, and she made claims in child support on what I owed and so on and so forth and got a felony warrant issued and the warrant was executed.”

The American coach of the Moscow-based team later waived extradition to Texas. Judge Henry Potter ordered Cunningham to be held in the Warren County Regional Jail in the meantime, and the head coach of the Czars would remain incarcerated well beyond game day against WKU.

Cunningham: “Come to find out when we got to Texas — actually, my court-appointed attorney in Bowling Green gave me case law that declared the law unconstitutional … You can’t extradite someone for a civil debt … The back support was eventually paid through the outcome, but it wasn’t nearly as much as she claimed it was. So, I would kind of like to leave it at that.”

According to AP reporting from 1992, “Cunningham has acknowledged that he was wrong for not making payments for the children … ” He declined to comment further on the matter for this piece.

Since the sole coach of the Russian Czars was completely out of the picture, Harbaugh had to make a decision — continue preparations to play the game, or cancel it? Even if everyone was on the same page about trudging ahead, he had to make an executive decision about how.

Harbaugh: “Lou Marciani is in a panic. I mean, he is in a total panic. ‘We can’t play. They don’t have an assistant coach. There was only one coach.’ And he said something like, ‘We got to get them a playbook.’ I said, ‘Nah, they know the plays. We don’t have to do that. What they do need is a head coach.’ So, I’m standing there looking around.”

Edwards: “I guess Lou and them were sweating — Lou was kind of that way anyway — that we weren’t going to have a game, but we had the game. Coach Harbaugh talked Lee Murray and Butch Gilbert, who were two of [former WKU head coach Jimmy] Feix’s full-time assistants back when he was still coaching, into helping him out. Lee was working at the university, but not as a coach, and Butch had retired. But they volunteered to help with the team that year because they were short on coaches with the budget cut and the staff didn’t have many full-time coaches.”

Harbaugh: “I go, ‘Lee, congratulations. You are now the head football coach of the Russian Czars.’ To which he looks at me like, ‘God, a shining moment in my athletic career.’ So, Butch Gilbert was also on Coach Feix’s staff back in the ‘70s and he was our kicking coach. He had been our volunteer kicking coach. So, I said, ‘Butch, I’m assigning you to be the number one assistant for Lee Murray coaching against the Hilltoppers.’”

Just: “When the event was over later that day, Jimmy [Clark] and I got in the car, probably mine, and we went to visit our friend in the jail downtown. By that time, the more subtle heads in the group had gotten together and asked Lee Murray if he could coach the Russian team. I think he said something like, ‘I will if you’ll get me an interpreter.’ So, Lee served as their head coach for that game. I think he still thinks this was quite an accomplishment.”

After Harbaugh helped the Russian Czars find just the right man for their coaching vacancy, he felt an obligation to the team’s players, who had “watched quietly as Cunningham was taken away,” Harbaugh told the Chicago Tribune in an article published on Oct. 16, 1992.

Harbaugh: “Well, you know, I said, ‘I need to do something. The team needs to know what happened.’ I mean, they just watched their coach just get handcuffed and leave the field. So, I called the quarterback, as I recall. I told him, I said, ‘You just saw what happened. They just arrested your coach. It doesn’t look like he’s going to be at the game, but we want to play the game and you know the offense and I’m sure other players know the defense. You can call your offensive and defensive plays, but we want to play the game.’ And he goes, ‘Oh yeah, we want to play. We came to play.’ So, I said, ‘Well, they arrested him.’ He said something like, ‘Well, coach, I’ve been in Russia for a year and a half, two years. Things like that happen over there.’ So the players probably weren’t too concerned by this, because according to him, things like that happened over there — at least that’s the story that I remember. I shouldn’t say he said it. I’m just saying that’s the way I remember it. So, we got that all worked out.”

Chapter IV: ‘I have never seen a man run so fast in my entire life’

After an eventful week full of twists and turns no one could have ever projected, WKU and the Russian Czars were both busy putting the final touches on their respective game plans. The Czars, now led by WKU assistant Lee Murray, had a quick turnaround before game time.

Harbaugh: “Practices were on the other side of the railroad tracks, over there where the track is now. We were separate. We weren’t together for any practice but that joint one.”

Quisenberry: “We would come out of our locker room, walk down the track, walk across and I was kind of the crossing guard to make sure that nobody got hit because you had to go across four lanes of traffic and then make sure you didn’t get hit by the train either. So, you can survive the traffic, but make sure that you didn’t get hit by a train either. We had two practice fields that sat there kind of catty-corner and there was like a 40-foot tall tower that was there that had a rope that I had to pull everything up — camera-wise — for practice.”

McGrath: “Coach Harbaugh was and is an incredible motivator. In typical Coach Harbaugh fashion, he had us ready to compete and we treated them like any other opponent.”

Jackson: “Even though they were semi-pro players, rugby and former Olympians, I felt that we were going to have a pretty good game and we needed to jump out on them early.”

McGrath: “He had us ready to play these great athletes from Russia. He built it up in such a way that we were not only playing for WKU but we were representing our country as well.”

Jackson: “I wanted to show them that USA football was dominant and I wanted to see how good they really were. Some of us aspired to be pro athletes and some of them were supposed to have pro experience, so it was almost like a test of our skills against their skills.”

Murray served as an assistant coach for the WKU football program from 1969 to 1977, but he’d “been working full-time in the property and real estate business, building condominiums and making a successful living for himself” for years before rejoining the coaching staff in 1992.

According to a piece in the Sept. 1, 1992, edition of the Herald, Murray wanted to “bring back a united family atmosphere” to WKU football, and he attempted to do the same with the Czars.

Quisenberry: “Basically [the Russians] needed somebody to manage the game per se so that they could say that they had a coach because [Cunningham] was the only coach that they had. Basically the players did everything else, but [Murray] was very into it. Even though on Thursday he was promoted to an interim head coach for them, he took it seriously. ‘OK guys, what do we need to do to get through this? I’m just here to kind of babysit you all,’ I guess you could say.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh traded Lee to the Russians to be their head coach for the game and I believe they gave Lee a jacket. My memory is that it was kind of a royal blue color, I think that was the color of their uniforms — might have just been white with a little blue on ‘em. But they gave him a Russian Czars team jacket to wear, the way I remember it.”

Jackson: “Coach Murray was my running backs coach at WKU, so it was weird watching him coach for another team.”

Quisenberry: “He was an old ball coach from back in the day. Just a great ol’ guy. I used to sit down and just love to listen to Coach Murray tell stories from back in the day — for basketball and football — because he had a wealth of knowledge and had been around forever.”

Murray, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “I have a great love for this university and the football program. It has been good for me, and I am proud to give something back to it.”

On Saturday, Oct. 17, 1992, game time finally arrived. Kickoff was set for 7 p.m. on a calm, mostly cloudy night with temperatures hovering around 50 degrees. McGrath said he still remembers his first time striking a player that was likely “five to 10 years older” than him.

Unfortunately for the Czars, their football skills were not equal to their athleticism.

McGrath: “I remember blitzing off the edge on the first play of the game. They ran a toss sweep and I met the fullback in the backfield and we had a huge collision, and I thought, ‘Wow, this could be a tough game.’ I later found out that the guy I was battling with all game [Vladua Pouzerieav] was [allegedly] the 100 meter sprint silver medalist in the 1988 Olympics.”

Quisenberry: “It was interesting because our guys, we would talk with each other and half of their guys wouldn’t understand English. We pretty much could say what was going to happen and they wouldn’t know. There were some — obviously the American players — who had a general idea, and they actually had their moments where they played us really tough.”

McGrath: “The fact was, we were much more skilled than them and our schemes were far more advanced. They were strong and fast, but they were behind in terms of football IQ.”

Harbaugh: “One play that I remember is they were punting from like their 15-yard line and they snapped the ball back to the punter and he took an extra step — a step, step and he took like a third and a half step. Well, the personal protector had backed up to protect and he backed right into the kicker and he kicked him right in the back — the lower part of his back — and the ball just dropped. I can’t remember whether it dropped in the end zone for a touchdown, but it was an easy score. When they blocked their own punt, I said, ‘Well, maybe we got a chance here.’”

Quisenberry: “They were wearing down, and we just continued to run the ball. Didn’t throw it very much. Of course, back then with Coach Harbaugh and the flexbone offense we ran, if you threw it five times in a game that was like throwing the equivalent of probably like 25 or 30 times nowadays. ‘Cause his idea of a pass was to run the ball on the edge and see if you could catch ’em ’cause we had some really, really quick quarterbacks and they were good athletes.”

Jackson: “Our defense was playing lights out, and our offense was moving the ball up and down the football field at will.”

The official stat sheet for the game shows the Hilltoppers built a 38-0 advantage to open the exhibition contest, but a Russian player listed as “Zwizna” — likely No. 22 Edward Zwisena, a 6-foot-2-inch, 225-pound running back for the Czars — was able to mount a memorable response for his squad when the game clock read 6:55 in the second period of action.

Harbaugh: “There’s an interesting play that took place in the first half. We kicked the ball off to them and this guy, number [22], he gets the ball on about the 15-yard line. I can remember it today like it happened yesterday. He caught the ball on the 15-yard line. He came down our sideline. I have never seen a man run so fast in my entire life. Whoosh! He went right by our sideline — oh my goodness — and scored. I mean, he took it 85 yards for a touchdown.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh likes to tell that on our special teams coordinator — that he let the Russians’ exhibition team run the kickoff back against us. So, that didn’t go over too well.”

Harbaugh: “Our kickoff coverage team had not been very good all year. We gave up a lot of big runs, returns on kickoffs and it just wasn’t good. As I watched him go for the touchdown — as a coach, you know — I said, ‘Give me the phone.’ I took the phone, and I said, ‘Get me the coach that’s in charge for the kickoff return. Put him on the phone.’ [The person on the other end] said, ‘He’s right here, coach.’ The [special teams coach] got on the phone and I said to him, ‘Listen, I knew going into the game that we were the worst kickoff coverage team in the United States of America. Now, listen to me, I knew we were the worst, but you have just taken our kickoff return team international. We are now the worst team internationally in the kickoff return.’”

McGrath: “The game ended up being lopsided, but I do remember our fans cheering so loudly because one of their [running backs] broke free on a kickoff return and scored. Our fans were so happy for the Russians because the game was getting out of hand.”

Jackson returned two kickoffs during the exhibition game, but he still vividly remembers his return after the Czars scored for the first time. Although WKU had “pretty much ran away with the game in every phase,” he still “felt embarrassed” the Russians scored on a kick return.

Jackson: “Their sideline was going crazy after the score … I was about to go into the game to return a kickoff after their score and I remember Coach Harbaugh grabbing my face mask and telling me to take it to the house. Meaning, ‘Score a touchdown.’ I went into the game and did just that. I returned that kickoff [93] yards for a touchdown.”

Jackson’s 93-yard kickoff return touchdown made the score 45-7 in the first half, and it became exceedingly clear that the Russian Czars simply couldn’t keep pace with the Hilltoppers.

Quisenberry: “I would say about halfway through the second quarter, they started to wear out a little bit and get tired because they weren’t used to the grind. Some of those guys played rugby, so they weren’t used to actually having pads on and being pounded on the whole time. Their conditioning wasn’t the same as our conditioning. Their idea of conditioning was to run a little bit, practice for 30 minutes, ‘OK. We’re good. Let’s take a smoke break,’ sit back and relax.”

Jackson: “We seemed to be much faster and more dominant the day we played them. It felt like the whole world was watching us. I remember being on the field with them and feeling like we were playing the Russians. It was surreal to me. I told my Mom and she was in disbelief.”

Just: “Most of their players had never played before they started putting this team together a year earlier or two years or whatever, and it showed. The quarterback was an American player, but he had played and then had a chance to play [in Russia] and he went. He wasn’t a bad player. It was an interesting game to watch — interesting because of the novelty of it, not necessarily interesting because of what a great matchup it was.”

Harbaugh: “After we went in and we had scored 40-some points in the first half, then we had a running clock in the second half — we ran it.”

Quisenberry: “Eventually we wore ’em down, and Coach Harbaugh wasn’t the type of guy that wanted to embarrass anybody. He wanted to get out there, not get anybody hurt, not embarrass anybody and gain extra reps for everybody. With our offense being a running offense by nature, I don’t want to say he called off the dogs, but he slowed it down. For us, the purpose was to work on what we hadn’t been doing good in the previous games and get ready for our next opponent. It was kind of another practice or scrimmage for us. It allowed the guys to get out there and hit on somebody else without hitting on their teammates.”

Harbaugh: “It was obvious that [the Russians] weren’t technically aware of our game, but they were great athletes. Big, strong athletes. So, it was an interesting experience watching these guys and kind of visualizing what they were in their particular sport and how nationally known they were in Russia because of their international experience.”

Just: “That was certainly one of the most interesting games [Harbaugh] ever coached.”

Claffey, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “You have to look at the fact that these guys have only been playing organized football for about two years. Despite the mistakes, the team can only get better. It is by far the best team in Europe.”

Despite the Russian Czars playing poorly under his guidance and a language barrier to boot, Murray still found a way to have a good time while coaching his very own band of misfit toys.

Quisenberry: “[Murray] had a great time. There was some jocularity, as it goes, during the game. Waving, ‘I know what you’re doing over there,’ and, ‘We know what’s coming,’ and just having a good time about it. He did a great job of keeping them in check and just managing the fact of, ‘You look tired. OK, you go in. I don’t know what your plays are, so you call your plays, but I’ll help make sure that the guys get subbed in if somebody looks tired or if somebody is injured, we’ll make sure that somebody is taken care of.’”

Murray, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “If [the Czars] had a year of real good coaching, they’d be a heck of a football team.”

WKU didn’t score after halftime, while the Russian Czars scored just once in the second half on a 1-yard rush from Zwisena with 40 seconds left in the final quarter. The final score ended up being 45-14, and Harbaugh quickly set out to find a particular player once the clock expired.

Harbaugh: “The game is over, and my mind is racing about what I had just seen — that guy running down the sideline. So, I’m looking around, looking for him and I look and I’m going through guys and I’m congratulating players, but I’m not really focused on congratulations. I’m looking for a number and somebody that I can look in the eye, right? So, finally I find him and he doesn’t speak English and I’m trying to tell him, ‘Have you ever gone to college and have you ever been enrolled in college?’ My thought was that if he hadn’t been enrolled in college, I was going to offer him a full scholarship. He was like, at that time, 26, 27 years old, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘We get him over here around our game for a year or two, I mean, this could really be something.’ Because he’d be like a pro and we’d get him for four years. [College players] didn’t come out early and all that stuff, so I thought we had a gold mine. Evidently, our languages, we didn’t connect, or he had played in college, I don’t remember exactly what it was. But that never came to being, and so that was one of the big disappointments.”

Click the PDF below to scroll through the game’s official statistics:

The Hilltoppers didn’t disappoint on the gridiron, putting on a high-scoring display against the Russian Czars. But the game’s reported attendance of 3,495 people failed to meet even the most modest benchmarks the WKU athletic department had set for the fundraising contest.

Clark said he and Just worked together throughout the week to get eyes on the exhibition game, which paid off when WKU and the Russian Czars were actually mentioned on ABC broadcasts, including a marquee college football game that kicked off at 2:30 p.m. on the day of the game.

Clark: “[Marketing the game] was just the novelty, I guess. We did, from a publicity standpoint, which was more of a Paul Just thing, have some national media coverage of the week.”

Chris Poynter (Herald special projects editor), writing for the Herald in 1992: “It was halftime of the Tennessee-Alabama game [on Oct. 17, 1992] when ABC sportscaster John Saunders looked into the camera and told a national audience that a university in Bowling Green, Ky., had found an innovative way to raise money for its financially ailing football program. Saunders then led into a five-minute piece about Western and its plight to generate dollars for football by playing the Russian Czars, billing it as ‘the International Football Classic.’ Little did Saunders know that the Hilltopper-Czars game wouldn’t live up to its expectations.”

Harbaugh: “ABC used to have that Wide World of Sports. They played that tape with that gal talking about it — ‘We’re here at Western Kentucky University’ — and they had the car driving out of the stadium with [Cunningham] in it after they arrested him. We made national news. It didn’t blow up our crowd any, though. We didn’t get any more people there.”

According to a front-page story included in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald, Marciani “had hoped [the exhibition game] would attract 6,000 people and raise $30,000.”

Instead, the university’s football program earned around $7,700. About 1,500 customers bought tickets, according to an editorial included in the Oct. 20, 1992, edition of the Herald. “Parking fees and concessions” aided net profits after the Czars were paid their $5,000 guarantee.

Just: “It seems like we drew a reasonable crowd, but wasn’t at all what we’d hoped. At that time, the stadium seated 17,500. We were hoping the novelty of it would fill it up. I don’t know whether it may have helped attendance with all this that went on around it in the closing days.”

Edwards: “We had a pretty good crowd. Not a normal crowd the way I remember it, but still a pretty decent crowd, which helped the budget, I’m sure. Somewhat anyway.”

Marciani: “Attendance was mediocre, but I think we raised something. It was not what we wanted to, if I remember, but we filled the date and brought attention to the football program and to the dilemma we had at that point, and that was, ‘Can we save football?’”

According to the Herald in 1992, “Marciani downplayed the attendance figure, saying that the cultural experience and the exposure on national television was enough to merit the game.”

Marciani, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “Everything can’t be counted in terms of dollars every time you do something. You always want more people to attend, but at least we made money … You take the net and run with it. I’m satisfied with the $7,000.”

Marciani and Harbaugh believed “the game was useful for the interaction of American culture with Russian culture,” and the two both insisted to local news outlets that “all [students] had to do was call the office” if they wanted to participate in the football team’s “cultural exchange.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “If the university didn’t take advantage of it, that’s its fault … If Joe Smith didn’t take advantage, I blame Joe Smith.”

Maggie Miller (WKU sophomore from Cleveland), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “More people should have turned out. These are the Russians, and they are playing football with us.”

Harbaugh jokingly said he harbors another bit of disappointment about the Russian Czars game, especially since the contest’s final score was a notch in the win column for WKU.

Harbaugh: “Paul [Just] and I had this discussion after the game was over. Coaches, we worry about our win-loss record, right? I said, ‘Certainly this is going to go into the win column.’ He goes, ‘No, it’s an exhibition game.’ I said, ‘What do you mean exhibition game? It ain’t no exhibition game. Stick it on my record.’ And I will report, it is not on my record. So, some disappointment came from the game from a selfish personal standpoint.”

Chapter V: ‘It would make a great movie’

Quisenberry remembers the Russian Czars “didn’t want to leave” Bowling Green after the game was over because the players on the team’s roster “were really looking forward to taking full advantage of what was going on in the United States.” He said he will never forget the week the Russians spent at WKU, and everything the Czars did for Quisenberry didn’t go unnoticed.

Quisenberry: “The biggest thing was it was cool to be able to meet somebody from a country that was supposed to be like the bad guy of the world and just kind of learn that, you know what, they’re not as bad as everybody put ’em out to be. They’re just like I am. As Woody Hayes used to say, they get up and put their pants on just the same way we do — one leg at a time. It was interesting to learn their culture and see how it was because for them, we were all friends for life. They might not ever see us again, but we were friends for life. That Saturday night, ‘I love you comrade. You’re my friend for life. If you ever come to Russia, look me up. I will take care of you.’ And that was the cool thing. I’ve never been there before or since, but I felt like I was part of their country for the five or six days that they were there. And the fact of they treated me just like their brother, you know? We were all one of them and to them, we were all one big family. It was cool and interesting to be able to take in that culture for a short amount of time. They went as much as they could, as far as like, ‘This is what was like, this is what it is now and we’re moving forward.’ It was a chance to basically learn a lifetime of history in five days about a country that all you ever heard about was how bad the country was.”

The Russian Czars departed for Chicago at 9:30 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 18, 1992, and returned to Russia shortly after, according to a report inside the Oct. 13, 1992, edition of the Herald.

According to an October 1992 AP article, the Czars were slated to finish their tour in December 1992 at the “first international football tournament.” Just said he didn’t “have a clue where they went or what happened to them after their visit here,” but he and Harbaugh knew one thing for certain as the rollercoaster week drew to a close: “[Cunningham] wasn’t gonna go with ’em.”

At the time, Harbaugh’s office featured a whiteboard he would often write on with dry erase markers. While inspecting his notes and beginning the necessary prep work for his team’s Homecoming game against Central Florida on Oct. 24, 1992, Harbaugh’s phone rang.

Harbaugh: “Sunday morning, I’m sitting in the office looking at the film and just reminiscing about the whole week and the phone rings and it’s Eldon on the phone. He goes, ‘Coach, I guess our guys played pretty well, huh?’ I said, ‘Well, I think it ended up like 45 to 14 and we played every guy on our team and we had a running clock in the second half. But you scored two touchdowns, the kickoff return and you got the last touchdown of the game. The guys really played hard, and you had some great athletes.’ He said, ‘I’m really happy about that. Do you think you could send the film down to Warren County Correctional Institution?’ I go, ‘I can send the film down, but I really don’t have a projector we can get to you so you can watch the film.’”

Following the Russian Czars exhibition, the Hilltoppers went on to post their best performance of the 1992 season, defeating nationally-ranked UCF 50-36 for their second win of the season. WKU stumbled down the stretch, finishing 4-6 after a 47-15 win over Murray State in its finale.

Money issues continued to plague WKU football, which posted losing seasons during two out of its next three campaigns. Program legend Willie Taggart led the Hilltoppers to a 7-4 mark during the 1996 season, sparking a streak of winning seasons that lasted until the 2008 campaign.

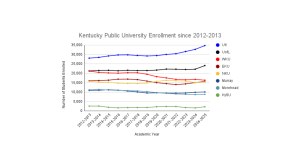

Since the university decided to preserve football in 1992, WKU has won numerous conference titles, won a Division I-AA National Championship, transitioned to FBS and posted a 4-2 record in FBS bowl games, finished with a No. 24 ranking in a final AP poll and built an entirely new half of Houchens-Smith Stadium, as the program’s renovated home field is now known.

Iracane and Marciani were both part of “a concerted effort to keep a piece of [the university’s] tradition alive” in 1992, and the two of them look back fondly on their decisions, even if some of “what [they] had to do wasn’t very popular” with other on-campus entities, especially initially.

Marciani: “When you look at the NCAA, they don’t like it when a school drops football. They don’t like it at all. I always told Dr. Meredith, [dropping football] might affect what conference we go to in the future. But he knew. He came from Ole Miss. I was never selling Dr. Meredith. He was always sold on keeping football despite the pressure of the Faculty Senate.”

Iracane: “I was the deciding vote [when the Board of Regents voted on the football program’s fate in 1992.] I voted to keep football, and that’s how it stayed. As it turned out Jack Harbaugh won a national championship in 2002. Obviously after that the football program took off and even much more success, a lot more success moving forward, and the rest is history.”

Marciani: “I knew football would determine what conference WKU would be in today and what conference the school could eventually go to. Without football, I think it would have been a very difficult movement for a proper conference, and here you are today — in Conference USA.”

Iracane: “I think any university would be different [if its football program was abolished]. There are several universities that do away with some athletic programs, and they bring them back. I also think athletic programs are a great supporter for raising revenue. A lot of alumni, that’s a big drawing point for alumni, and whenever you have a successful program, the giving rises.”

Marciani: “That decision [to fund the football program “no matter what it took”] probably cost me a job at WKU because those decisions I made were not very popular, and Dr. Meredith knew that. It was worth the amount of energy that I put into it because you look at the program today and what it means — the university is completely different. It’s really, really different. They have done a great job in elevating that program to a very nice level right now.”

Iracane: “Well, [Jack Harbaugh and I] hugged and kissed [after football was saved]. They had a ceremony after they named the [stadium club] after him and he called me and invited me back. We all went out there together and everybody took a bow because they built that beautiful stadium. What a waste that would have been if we didn’t continue to play football.”

Clark arrived at WKU as an intern in August 1991 and was selected to fill the vacant position of coordinator of marketing and promotion in the athletic department in August 1992. He left the Hill from 1993-2000 to serve as the development associate at the University of Mississippi.

Since returning to the Hilltoppers’ athletic department in 2000, Clark has remained at WKU. Clark said the difference in culture between his first stint at WKU and now is striking.

Clark: “From a facilities standpoint to community support it’s light years ahead of where we were at that time. Just the community, the university, everything has gotten behind WKU Athletics. It’s almost like a totally different place.”

While reflecting on the events of 27 years ago, Cunningham said he wanted to focus on “the team and the kids and the game” — the three aspects he wanted to focus on back in 1992.

Cunningham: “The good part was it was a great experience for the kids. They got to see firsthand what real football was about. In the early days in Europe it was never consistent as far as referees and umpires and so on and so forth. The thing about going to Russia is we literally had to teach umpires, our referees. It was a start-to-finish type thing. Heck, I even had to come up with cheers for the cheerleaders, which was a novel concept for ‘em — for me too. But the kids got to see and play in the States and it was just an overall — except for my moment — great experience for everybody, and that’s what it was about.”

Those who experienced the so-called “Battle of the Big Reds” — as the Fall 1992 edition of The Honorable Mention newsletter dubbed the exhibition — firsthand said they will never forget the contest, especially since it was a part of the 1992 season that set WKU up for future success.

Harbaugh: “Well, a lot of fantastic things have happened in my coaching career, but that experience with the Russian Czars, that was one of the amazing experiences.”

Marciani: “It was a blip in the history of the school, and we turned it from a blip to a plus-plus. I think you learn from history, and you get better at it when you go through these experiences. My fondest thoughts are that every effort by many people to maintain football at Western Kentucky was worth every ounce of energy so that students can enjoy it today, and also the athletes, the state and the region. I’m proud to say that even though I went through a little bit personally, I enjoyed my stay. It was an honor for me to serve the Hilltoppers, no question about it.”

Harbaugh: “I don’t know what they call it, but they’re little dolls and you put a smaller one in a bigger one and there’s about seven or eight of them you do that with. Jackie, my wife, she bought [Matryoshka dolls] and we still have ’em as memorabilia from that experience.”

Just: “It had Jimmy [Clark] and me running around quite a bit for about four or five days. All the calls about it — if there was a problem anywhere, they probably wound up on his desk or mine. It was certainly unlike anything that has ever come to this town.”

Edwards: “Highly unusual to have something like that during our regular football season. If you tell that story that we played the Russian team, nobody would believe you, you know?”

McGrath: “It was a great week filled with many memories. Our 1992 team was special for many reasons. Many have said we were the team that saved the program. That week, we were also a team representing Western Kentucky University and our country.”

Harbaugh: “It was so meaningful, and the experience was one of those highlight reels that you get a chance to play through a career. You have 46, 47 years of coaching, but that experience, that evening and that opportunity was one of those highlight reel type experiences. I swear as I look back at it now, it would make a great movie. I mean, you could. The whole week.”

Sports Editor Drake Kizer can be reached at clinton.kizer287@topper.wku.edu. Follow Drake on Twitter at @drakekizer_.

Projects Editor Matt Stahl can be reached at matthew.stahl551@topper.wku.edu. Follow Matt on Twitter at @mattstahl97.

Elliott Wells contributed reporting to this project.