Opinion: Political parties and polarization: Does having two political parties make us hate each other more?

March 3, 2020

Democrats and Republicans are more divided now than at any point in the last 25 years. And while there is nothing new about parties disliking each other, the intensity of hate is greater than it has been in a long time.

Politics seem to be seeping more and more into every aspect of life, and though college students often say they don’t care about politics, the number of college students who voted nearly doubled from the 2014 to 2018 midterm elections, according to a report from Tufts University Institute for Democracy & Higher Education.

In my American literature class, fierce debate erupted over immigration and race relations.

And while the two students going back and forth probably have a lot of things in common considering they’re both English majors, it seemed they could not get past their ideological differences when one student identified himself as conservative.

Thomas Rowe, a senior English for secondary teachers major, considers himself a “conservatarian” — a fusion of conservative and libertarian — making him an outlier in an English class taught by a professor who strongly identifies as a progressive liberal.

The heated talk between students has its roots in the rising partisan animosity that has been growing nationally for some time.

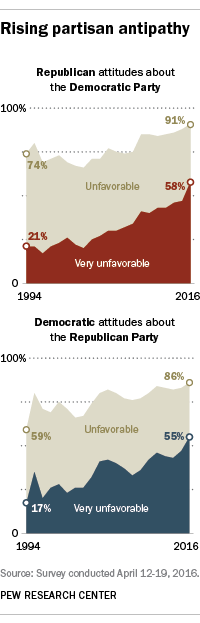

In 1994, only 21% of Republicans had very unfavorable views of Democrats — similarly, only 17% of Democrats had very unfavorable views of Republicans, according to the Pew Research Center.

These numbers of strong dislike have nearly tripled, and it has led to people’s inability to compromise and find common ground.

Rowe said he thinks the two-party system creates an “us versus them” mentality.

“There are approximately 325 million Americans,” Rowe said. “Do we really believe that we can all easily fit into only one of two boxes? The answer is obviously no, we cannot.”

He said the rise of the “tea party” movement began the split within the Republican party, and Trump’s election further increased the divide because of the “never Trump” faction. And on the left, the rise of Bernie Sanders and socialist sentiment has splintered the Democrats.

So why do we still only have two parties if Americans’ views are growing further from the center?

Scott Lasley, head of WKU’s political science department, said via email that the two-party system is a consequence of a number of institutional factors such as the existence of single member plurality districts and ballot access rules.

Single member plurality (SMP), Kentucky’s voting system and the most common in the U.S., works with geographically defined districts that send one representative to a legislature. Voters cast a single vote, and the winner takes all.

“The American two-party system has shown itself to be quite durable and is continuously evolving,” Lasley stated in an email.

“One factor in the equation is that parties developed in part to help meet the goals of the individuals who created them. Change would be most likely to occur if they no longer meet the needs of ambitious politicians. That has not happened, and there is not a lot of evidence to suggest that it will happen anytime soon.”

He added that two-party systems have often been fairly moderate and less polarized than other systems.

“Increased polarization in American politics is a lot more complicated than just saying that it is the result of a two-party system,” Lasley said.

Of the several political science professors I contacted, all were quick to separate the ideas of political parties and polarization.

Timothy Rich, WKU associate professor, said polarization also occurs when there’s more than two parties, but Americans would prefer more options.

“It’s not just that they [the U.S. public] want more options on the ballot, as most presidential and legislative races have candidates with no chance,” Rich said in an email.

“They want candidates and parties that might win a few seats … There is also decades of research in other democracies showing that satisfaction in democracy tends to be higher where there are multiple viable parties, especially under proportional representation (PR) systems.”

Rich brought up several more alternatives to the single-member plurality system, such as the alternative vote, in which voters rank candidates on the ballot. This system is used in Nevada.

“This system eliminates wasted votes and strategic voting, encourages smaller parties and usually generates a candidate that is fairly moderate compared to the district’s voters,” Rich said.

However, third parties could also create a less stable political system.

Jeffery Budziak, WKU associate professor, said that a downside of multi-member systems with third parties are potentially wilder swings in types of government from election to election.

“There are countries that have these systems that go from having a borderline facist, kind of right-wing government to a socialist communist government from election to election,” Budziak said. “We kind of force everything in our system to the middle.”

He said two parties are not the cause of political polarization. Instead, people loading their identities on top of each other is the leading factor.

Budziak said that knowing someone’s demographic information, like their religion and race, is much more telling of their political beliefs than it used to be.

“If you’re a non-religious person of color living in an urban area, I have almost mathematical certainty that you’re a Democrat,” Budziak said. “And if you’re a Christian white male living in a rural area, I have almost mathematical certainty that you’re voting Republican.”

He said since people load all their identities up, someone whose party is criticized also feels like the rest of their identities are being attacked as well.

Part of the solution, Budziak said, is meeting people who are not in your tribe. He said it’s obvious that we should be friends with those of differing beliefs, but the reality of how to do that is the hard part.

“Everything is becoming sorted,” Budziak said. “People’s lives are more sorted. Thinking about how we forge group identities that cut across these cleavages, one thing I tell students is to join local community groups.”

He said local politics, something even as simple as fixing potholes, involves a lot less partisanship.

“My guess is that being Democrat or Republican does not really dramatically change how you fix the potholes in the road,” Budziak said. “And so getting people active in local and state governments is really valuable because you meet people with differing political backgrounds who actually agree with a lot of the things you’re doing.”

Unfortunately, the media has become increasingly nationalized, and people think nationally when they think about politics, causing them to jump into their separate camps.

Budziak added that becoming involved in local affairs requires you to interact with people in real life, rather than staying in online communities where it is very easy to cluster yourself within your tribe and be mean to people.

Finally, Craig Cobane, executive director of the Mahurin Honors College, said that the problem is not too few parties or the wrong types of parties but that the issue lies in too much state power.

“To what lengths would people and parties go to have the ability to make laws and edicts that impact hundreds of millions of people?” Cobane said.

“Similarly, think about the types of groups and people attracted to having that type of power and control. Why do they sacrifice so much to get that power? Where it is a two party or multi-party system, you will still have the same problem.”

Overall, the current U.S. political system thrives on politicians attacking their opponents to get reelected. When politicians, cable news and online influencers are constantly bashing the “other side,” it becomes difficult for the common American to stay level headed.

So while the two-party system may not be a direct cause of polarization, anyone with eyes and ears can tell that the parties are radicalizing and political discourse growing more unpleasant by the year.

Opinion editor Jake Dressman can be reached at jacob.dressman200@topper.wku.edu