Students study the forgotten history under their feet

December 3, 2019

Fifty-two years after the Jonesville residents — a Bowling Green African-American community — relocated, students in John Conley’s English 100 classes have dug deep into WKU’s forgotten history, which, according to Conley, was assigned within the context of a national conversation about the longstanding injuries that have been done to black people in the U.S. and in the context of a growing nation- al conversation about reparations.

“We’re working on a unit in which the students are encouraged to learn a little bit about the history of Jonesville and to kind of sit with that knowledge and to try to notice, then think about, then write about the history right under our feet on Western’s campus, how that impacts the way we under- stand ourselves as members of this university community,” Conley said.

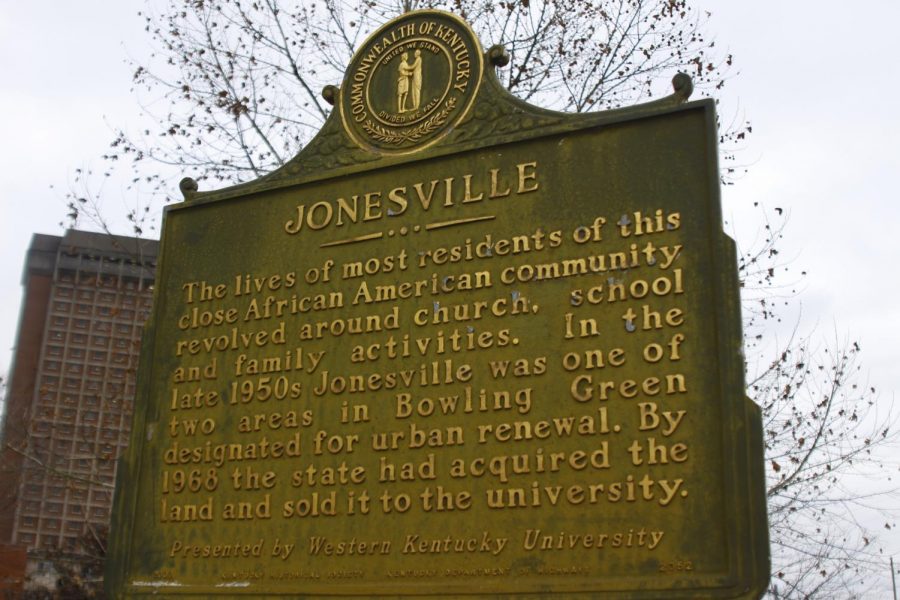

If a student passed by the marker that stands just past Nick Denes Field on the outskirts of WKU’s campus, they could read that a community called Jonesville was bordered by Dogwood Drive, Russellville Road and the railroad tracks.

From 1881 to 1967, Jonesville was a neighborhood with a predominantly black population. At its height, 400- 500 people called Jonesville home and around 70 homes were peppered within it. A church stood as the center of the community — a church where Maxine Ray remembers attending Valentine’s Day parties and listening to ghost stories in a neighborhood many at WKU don’t know anything about.

Ray is one of the few people left who remember growing up in Jonesville. She was born there, along with her grandmother and mother. She played softball in vacant lots and borrowed books from the small library at the church.

And when asked what Jonesville looked like to her growing up, Ray gave a wistful smile and a single word:

“Home.”

Home was a small community where everybody knew everybody. Home was where her parents provided everything they needed and where Ray didn’t know that her mother worked until junior high because her she was always there when Ray came home from school.

“I can’t remember growing up and seeing someone in our community that was hungry, because we all shared, we all knew each other,” Ray said. “Ev- erybody had a garden, so nobody was ever hungry.”

When Ray was 18, she married young and moved out of Jonesville. Her parents and grandparents still lived in the community, and the university had been trying to buy the properties that made up Jonesville since the 50s.

“They fought it and fought for a long time, as best as they knew how during that time,” Ray said. “It was 1954, ‘55, ‘56 – Martin Luther King had just started his non-violent movement – and I don’t think our parents realized that they could have gone out of state and gotten an attorney to help fight it.”

Ray remembered the next sequence of events clearly: the state condemned everybody’s property, then Urban Renewal came in and bought all the prop- erty and then sold it to the university. Everyone in the community owned their property and had what Ray called “clear deeds.”

“That was really hard,” Ray said. “Re- member, it’s segregation — you can’t walk into a bank and get money for your property.”

Ray said most families that lived in Jonesville found new property. She recalled her mother talking about going to the bank to get enough money for their house and her grandmother’s house.

“We never move as a neighborhood together, it was spread out around the city,” Ray said. “It wasn’t too far spread out, there were only around four sec- tions, four parts of town that blacks could live in, so we never were together again as a community.”

Conley, like many others, came to WKU with no knowledge that Jonesville had existed. He saw a number of signature meeting places for the WKU community like Diddle Arena and Houchens-Smith Stadium and had no idea that half a century ago, there stood a thriving neighborhood.

“Personally, I love teaching at WKU,” Conley said. “I love my students and I love our mission to provide a high quality, accessible education to the students of south-central Kentucky and our service area. But I think that if Western as an institution is unwilling to account for how it got to where it is today, I think it risks to lose a lot in the long run.”

News reporter Abbey Nutter can be reached at abbigail.nutter168@topper. wku.edu. Follow her on Twitter at @ abbeynutter.