MR. WESTERN

May 15, 2019

After watching WKU thump Pikeville in its exhibition, Lee Robertson was on the move again to see yet another Hilltopper the next morning— Dr. Craig Beard, a former football player and a current orthopedic surgeon.

Robertson’s knee, the same knee he tore up while pitching for WKU, required replacing. His energetic lifestyle that had been a staple of his personality for years finally caught up with him.

“At 92, I’m still pretty active,” Robertson said. “Mentally and physically. I don’t know how long it’ll last, but I don’t need to go sit down in my house and twiddle my thumbs.”

However, because of his age, there was reasonable cause for concern about surgery.

But Beard told Robertson that being as lively as he’s been, he had no anxiety regarding the replacement.

Sure enough, less than two weeks later— despite a swollen left knee and bruising that extended down to his ankle— Robertson made it back to Diddle, on the campus of his second home, in the same seat: section 105, row F, seat 1.

“He wanted to be there so badly,” Joyce Robertson said. “That’s just his mentality.”

He left the hospital that morning to watch the football team notch a 45-7 win over the University of Texas at El Paso on Senior Day before making his way to watch the basketball team drop a 64-63 decision to Belmont University. He then checked back into the hospital that night.

Despite his apparent discomfort, his spirit never wavered.

He still welcomed the handshakes, the hugs, the pictures, and even with the pain, his eyes lit up after a successful fast break and his hands, like they have for near a century, clapped incessantly in support for the school he’s been around nearly all his life.

That’s just who he is. He’s Mr. Western.

“This place is so meaningful to me,” he said. “It’s my home. It’s me. It’s my life— it has been.”

Today, you can find Robertson working diligently in the Wetherby Administration Building, Room 114, on his tasks as fundraiser and special assistant to the vice president for Development and Alumni Relations.

If he’s not utilizing one of his 100 days he receives as a form of teacher retirement, you can catch a glimpse of his unwavering friendliness upon entering the Augenstein Alumni Center in the form of a bronze statue, or “Old Lee in Bronze” as he likes to refer to it.

The university also named a ballroom in the alumni center after Robertson during its construction in 2013.

“I have thought how fortunate he’s been, but also he has given himself to Western, and they’ve given back,” Joyce Robertson said. “It’s been a wonderful companionship.”

Robertson also was named the first-ever Spirit of Western award winner in August of 2002. The award recognizes an individual who represents enthusiasm for WKU, loyalty to the institution and principles of the WKU experience and its motto, “The Spirit Makes the Master.”

“He’s a unique person because he’s really the embodiment of the tradition feel of this institution, which is continued about ‘The Spirit Makes the Master,’” said Kathryn Costello, vice president for Development and Alumni Relations. “He lives and breathes that.”

In 2005, Robertson was named to WKU’s Hall of Distinguished Alumni, which recognizes the outstanding accomplishments of alumni who have made significant contributions in their field.

Whether he claims to be deserving or not, he’s up there for a reason.

“When I look at those bronze heads in the alumni center and see what some of them have done I say, ‘I don’t deserve to be up there with that gang of people,’” Robertson said. “It choked me down.”

In 2007, Robertson received the Paul J. Just Award for outstanding contributions to WKU athletics for his career as a baseball player and golf coach.

“When you’re talking to him, you’re the most important person in the world… There’s not a fraudulent bone in his body,” said Just, WKU’s sports information historian.

Maybe the biggest reward of them all is the countless relationships Robertson has made throughout his time at the university.

“When he was turning 90, we said ‘Lee, would you make a list of people that you think you’d like to invite to your birthday party?’” Costello said. “700 names. He could sit down and write 700 names of people he knew well enough to invite to his birthday party.”

With a mind like a steel trap, Robertson never comes up short of calling anyone by his or her first and last name—because if you’re a part of the WKU family, you’re a part of his.

“That’s what it’s all about— family,” Robertson said.

In 1948, 1949 and 1950, Robertson lettered in baseball under Diddle. Despite his above-average skill set, his time as a WKU baseball player was limited.

On a cold, rainy March day in 1948, while pitching against the University of Louisville, he injured his left knee.

“I was up there, and I slipped and tore my knee completely up,” he said. “… (Diddle) came out and got me and picked me up in his arms like a baby and he said, ‘Robby it was a good time for it to go out. The bases are loaded and nobody out.’”

Robertson remained on the team for the next three seasons and saw spotty time on the field, but what he took most out of that experience was his time with Diddle.

He graduated in 1950 and used that experience to begin teaching and coaching at Park City High School until 1952 when he went back to McLean County to do the same at Livermore High School— an archrival of Calhoun.

It was at that time Robertson met his eventual wife, Joyce Bennett, who lived a hop and a skip away in Calhoun, but had never come in close contact with him due to a 10-year age difference.

Like many other people in Robertson’s life, she was taken aback by his gregarious personality.

“I had gone to college at Murray and came home in the spring,” she said. “I was in the backyard having washed all my clothes from college and hanging them on the line, as we did then, and this car drove up in the drive and he said, ‘Hey! You want to go to Park City with me to pick up my clothes?’ Well, it was Lee.”

The two soon became a couple. Joyce transferred to Kentucky Wesleyan to stay closer to her significant other, who was still at Livermore. They were engaged by December 1952 and married on April 2, 1953.

In 1957, Robertson completed his master’s degree and found himself on the move again, this time with “Mama Joyce,” as he deems her, to Glasgow as assistant superintendent of Barren County schools. By 1958, he advanced to superintendent.

But it wasn’t long before he got a chance to come back to WKU.

Former WKU President Kelly Thompson urged Robertson to become director of the alumni program and the placement services program.

“I didn’t know what either one of those meant, and Kelly Thompson didn’t know, either,” Robertson said. “So I asked him, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ He said, ‘You need to come and find out.’”

Despite the uncertainty and a lower salary, Robertson took the job.

“I was in the right place,” Robertson said. “I’ve been pretty dang lucky to get where I am.”

His personality and work ethic allowed him to orchestrate several successful projects while head of Alumni Affairs and Placement Services, which included bumping up the number of on-campus clubs from one to more than 50.

He held the title of alumni director until 1985, when he made the decision to retire at age 62 after holding the position for 25 years.

But it wasn’t long after his retirement that he felt empty.

“I was sitting at home and my wife, Mama Joyce, said you’re the most unhappy man I’ve seen since I’ve known you,” Robertson said. “I was twiddling my thumbs and playing solitaire. I didn’t know what to do.”

Robertson opted to help a former baseball teammate with a project in a lumber company in Bartow, Florida, but after that ended in a year, he returned to looking for fulfillment once again.

He wanted to come back home.

“They said, ‘We want you to come back and direct our Glasgow campus,’” Robertson said. “I jumped at that opportunity because I loved to be around Western.”

The WKU Glasgow campus was just getting started, and Robertson helped nontraditional students in a 10-county radius who couldn’t travel to the main campus in Bowling Green.

He changed their lives.

“I was out to promote this new venture,” he said. “I called on superintendents of schools, court house executive judges, corporation CEO’s— all the big shots… It was so easy to do and so much fun because everybody was for you.”

When a full-time director was found for the Glasgow campus after Robertson made his mark, he found himself twiddling his thumbs once again, but not for long. The university that has never let him down picked him right back up again.

First-year WKU President Gary Ransdell brought Robertson back to the Alumni Affairs Office in 1997 to guide the fundraising process, which is where you can still find him today.

“His relationships are deep,” Ransdell said. “And he is always there and ready to do whatever the university needs of him. I think the university is an integral part of his life and that of his whole family.”

The late Jimmy Feix— the athletic director at the time— also offered him a position as golf coach, which gave Robertson as many responsibilities as ever.

“(Jimmy) wasn’t a golfer,” Robertson said. “He didn’t know what it took to be a golf coach, I guess. He knew I’d hacked around at it all my life. He knew I wouldn’t turn him down.”

Robertson’s plan was to coach for a single season, but he extended that to six years in accordance with the need from the athletic department and finished with a 364-361-7 record.

Although he spent six years as head man, his most memorable time on the course came when he wasn’t coaching. During a friendly match in 1998, Gordon B. Ford, a graduate of Bowling Green Business University, expressed to Robertson his interest in having the business college at WKU named after him and his mother, Mattie Newman Ford.

Robertson and other WKU officials then received a hand-written $10.6 million offer from Ford— the largest gift to the university at the time— leading to the college’s new name, the Gordon Ford College of Business.

“He mentioned somewhere: if it wasn’t for Lee Robertson, you all wouldn’t have gotten this,” Robertson said.

Just recently, Robertson and the fundraising department received a $1 million donation from Don Dizney—a friend of Robertson’s for 40 years—for The Medical Center-WKU Health Sciences Complex, which was completed in 2013.

“That fundraising—it’s not rocket science,” Robertson said. “It’s building relationships and not trying to go too fast. It’s not any magic that I have. It’s tenure. It’s longevity, and it’s compassion for your fellow man.”

Robertson grew up in Calhoun, Kentucky, a 448-acre city in McLean County with a current population of less than 800 people.

He attended elementary and high school in his hometown, graduating from Calhoun High in May 1941. Six months later, Robertson, a good old down-to-earth country boy, joined countless young Americans who stepped up to defend their country.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the amiable high school graduate found himself heading into unfamiliar territory.

“I didn’t know what Pearl Harbor was, or where it was, or how it was,” Robertson said.

But the next summer, he became a soldier in the U.S. Army, and a year-and-a-half later, he sailed to the jungles of New Guinea for full combat.

Robertson, who rarely left Calhoun, found himself 8,823 miles from it. But he brought the strongest staple of his personality with him—optimism.

“The Army has a way of regimenting you,” he said in an upbeat voice. “Dang it, that’s good. The Army is good for you.”

Robertson’s positive nature allowed him to enjoy his time in World War II, but it was obviously far from a walk in the park. He and a fellow trooper overcame a near-death experience during a night battle toward the end of the war in the Philippine Islands.

“When we flew up there in troop carriers, (the Japanese) were crawling in our area,” Robertson said. “There was one Japanese with a hand grenade raised that was between me and the highway where the vehicles were, which silhouetted him easily. One of the guys that was under the tank with me fired on him, hit him and killed him. But he was getting ready to let that hand grenade loose in our area.”

Robertson spent 38 months in the Army before heading home on Dec. 24, 1945, the same day his brother, Sam, returned.

“You could say we had a pretty good Christmas that year,” Robertson said.

The Army did two things for Robertson: it systemized him, and it earned him opportunities in the form of the G.I. Bill. The latter led him to a decision that continues to define his life going on a century later.

“The next spring in ’46, one of my buddies came by in the afternoon and said to me, ‘Lee, let’s go to college,’” Robertson said. “I said, ‘OK, where is one?’ He said, ‘Over there in Bowling Green.’ I said, ‘Let’s go!’”

Robertson enrolled at Bowling Green Business University and opted to study cost accounting. It didn’t take him long to realize that route wasn’t meant to be, spurring him to consider a different option.

Shortly after, Robertson pitched for an independent baseball team from Morgantown, Kentucky, which landed him $25 a game, including a game on WKU’s diamond against Bowling Green. He pitched seven innings and managed a couple hits to go along with his impressive outing on the mound.

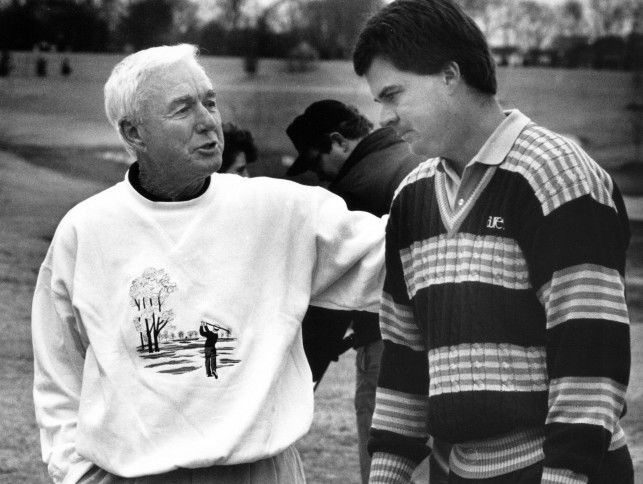

E.A. Diddle, who coached the WKU baseball team at the time, was in the stands at that game to watch Robertson pitch. Robertson became fond of Diddle and decided to follow in his path. Robertson yearned to become a coach.

In fall of 1948, he enrolled at WKU— one of 1,100 to 1,200 students at the time—and began his health and physical education degree with minors in English and biology with the expectation of teaching while coaching.

A man walks into a basketball arena on a cold, early November night while the home team gears up for its lone exhibition game of the young season.

He takes his usual route, maneuvering through fans on the way to the seat he’s grown accustomed to for a half century: section 105, row F, seat 1.

He’s no stranger here. He’s walked this walk many times. He’s strolled through Western Kentucky University’s Diddle Arena and just about every inch of the campus more than most could fathom.

Less than 25 feet from his seat, folks bombard him with admiration, handshakes, hugs, pictures and other countless signs of affection— many that in one way or another he positively influenced during five decades at WKU.

“You can tell right away, I’ve been here for awhile,” the 92-year-old man says.

It takes the conclusion of the “National Anthem” before he finally finds time to sit down.

Before the basketball is tipped, he notes that the team’s shooting shirts worn in pregame warm-ups weren’t “tough enough.”

During the game, grunts resonated from his general direction every time a WKU player made a miscue.

“Take it to the basket,” he said after a player clanked a 3-pointer off the back of the rim with more than 25 seconds remaining on the shot clock.

To his delight, the team won 105-84 that November night. But that didn’t stop him from identifying possible areas for improvement. He’s always wanted the best for the school and for the people who attend it.

That’s just who he is: Lee Robertson, a WKU graduate and icon.