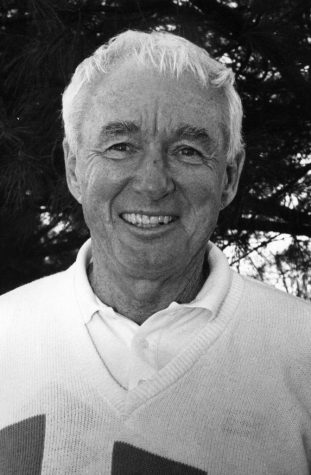

Giving his blessings away: Alum helps students in need

October 1, 2018

Last fall, a group of around 10 students huddled near the television inside the lounge at the Cynthia & George Nichols III Intercultural Student Engagement Center on campus. George Nichols III, one of the center’s namesakes, was seated alongside his wife, Cynthia Jean, at the head of the gathering. Nichols and his wife went around the room and asked each ISEC scholar to answer one simple question for him: “What can we do for you?”

Alexis Watkins, a sophomore music performance major, said she was worried at the time that she might not be able to return to WKU in the spring. So, when Nichols got to her, she asked him for a scholarship.

“By the end of the meeting, everybody had told them what they wanted,” Watkins said. “Mr. Nichols told me, ‘I’m going to pay for your tuition next semester.’ Then he granted what everybody else had asked for too. After that, honestly, I cried. I was shocked, and I just had to hug them. I called my sister and told her, ‘Somebody just legit offered to pay my tuition.’”

Watkins, who comes from a single-parent household, said Nichols’ gift gave her the security to further her higher education career without having to worry about placing a financial burden on her mother.

For Nichols, he feels fortunate that he has the opportunity to help others. He said he and his wife are always looking for ways they can help somebody have a chance to succeed.

“Every time I look around, there’s someone or something that is being provided or given to me that I define [as] a blessing,” Nichols said. “The only thing I know to do is to give that blessing away. The amazing thing for CJ and I is that every time we give our blessings, we get more blessings, which means we need to give more blessings away.”

As part of the festivities last Friday, CJ & George Nichols III were able to visit @WKUISEC with President @caboni to see their philanthropy in action. Read more about their gift at https://t.co/p3qQg927rk. pic.twitter.com/86UiDz88ls

— WKU Philanthropy (@wkuphilanthropy) April 30, 2018

Nichols, 58, was born and raised in Bowling Green. His family was poor and Nichols said his mother and father both worked extremely hard to make ends meet. Nichols lived on Main Street during his early childhood, but he said his family yearned to move to a better area even if it wasn’t the most conventional move for them to make.

“We were renting an old, raggedy house, and we wanted to move to the projects because we felt that would be a step up,” Nichols said. “But because my dad worked all these jobs, we made like $50 more than the financial cut-off to be able to move into the projects. I remember how devastating that was, but my dad was able to buy a house that sort of outlined the projects through a government program.”

Growing up, Nichols played basketball at Parker-Bennett Elementary School. Nichols said police officers volunteered at the facility during after-school hours so kids would stay off the streets.

One of the officers who volunteered at Parker-Bennett also worked security for varsity basketball games at Bowling Green High School. Nichols said the officer told the school’s varsity coach about a “young black kid down in the projects that could jump out of the gym.”

Eventually, the coach came and saw Nichols play. He told Nichols, who was only a sixth-grader at the time, “I’ll be watching you.” By the time Nichols got to junior high, he said all the white kids knew his name.

Nichols befriended Tim Riggs, whom he called the “longest, oldest friend I’ve ever had in my life,” at the age of 13. Nichols said Riggs did not care about how good of a basketball player he was. Rather, Riggs cared about him as a human being.

“The first few times I went to Tim’s house, his mother invited me to have dinner,” Nichols said. “I’m sitting down at the table with Tim’s father, Col. Gary Riggs, who comes home dressed nicely and talking about his workday. That experience of watching a family unit where the father was a professional made me think that maybe I would try to get a job where I use my brain instead of my physical being.”

Though both of Nichols’ parents quit school in the sixth grade, Nichols said they encouraged him to get a college education and “break the cycle of poverty” that had plagued his family.

After a standout prep career at Bowling Green High School, Nichols graduated in 1978 with a basketball scholarship to Alice Lloyd College in Pippa Passes, Kentucky.

Nichols said he always dreamed of bringing an NCAA championship to WKU, but he was not offered a scholarship due to his size. WKU assistant coach Clem Haskins wanted Nichols to develop his game at the junior college level for a year and then come back to Bowling Green, but Nichols decided against it. He remained at Alice Lloyd until he received an associate’s degree in sociology in 1980.

By the time Nichols arrived at WKU in 1981, Haskins had been promoted to head coach. Haskins offered Nichols a spot on the team as a redshirt, but Nichols said he declined in order to focus solely on academics. As one chapter of Nichols’ life was closing, he said another one was beginning.

Nichols met his wife of 34 years, CJ, shortly after starting classes on the Hill.

CJ graduated in 1982, while Nichols did not receive his bachelor’s degree in economics and sociology from WKU until 1983. His wife returned to Shelbyville, Kentucky, after graduating, and the young couple was forced into a long-distance relationship during Nichols’ last year at WKU. Nichols said he started working on his master’s degree during that time, and by the time he graduated, he had multiple offers for graduate assistantships.

“Vanderbilt, to me, was like the Harvard of the South,” Nichols said. “I always hoped that I was smart enough to get in, and I was accepted at Vandy for graduate work. But, I was also accepted at Louisville. I was engaged by then, so it made more sense for me to go to Louisville. I had tuition paid, I had some financial assistance and the woman I was going to marry already had a job there.”

Nichols received a master’s degree in labor studies from the University of Louisville in 1985. Nichols’ academic advisor helped him get an internship at Central State Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Louisville. After three months, the hospital’s director became commissioner of the Department for Mental Health & Mental Retardation Services in Frankfort. The newly-appointed commissioner asked Nichols to join him as an executive assistant.

Nichols said he accepted the position, but only on one condition: no nights or weekends. The commissioner honored his request, and Nichols began conducting management audits of hospitals and community mental health centers. Before long, the commissioner gave Nichols another new job opportunity.

“After four and a half years, he asked me if I would go back and be the director of Central State Hospital,” Nichols said. “The hospital was going through some accreditation issues, and we turned it around in about six months. I was only 28 years old when I went to run the hospital, and when word got out about this young black guy that’s turned around the state hospital, I started getting people calling me.”

As a result of his success, Nichols accepted a position with the Kentucky Blue Cross Blue Shield plan, where he worked for about three years. He later got a job on the Kentucky Health Policy Board, which was abolished only six weeks after Nichols became its executive director. Shortly before his position disappeared, Gov. Paul Patton asked Nichols to become the state’s insurance commissioner.

Nichols served five years as Kentucky’s first African-American insurance commissioner, and he also became the first African-American to be elected president of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

During his time as insurance commissioner, Nichols was also chairman of a committee focused on the integration of banking and insurance. He said a merger between a large insurance company and a large bank in the late ‘90s helped him become “the spokesperson for the insurance regulatory community.”

After speaking around the world about regulation, including before Congress, Nichols said he was recruited by the chairman of New York Life Insurance Company. He started his career at the company in January 2001 and has held numerous positions within the company, including his current role as executive vice president.

Nichols has also received numerous accolades during his 17-year stay at New York Life, including being named on Savoy Magazine’s list of “Most Influential Blacks in Corporate America” in 2012 and 2018. After a long and fruitful career, Nichols said he recently decided to leave New York Life and accept a new position.

According to a press release, “The American College of Financial Services…named George Nichols III…president and chief executive officer beginning November 1, 2018.”

Nichols said even though he has enjoyed all his previous positions, one of his “fantasy jobs” has always been becoming a university president. Since Nichols does not hold a doctorate, he thought he would never achieve that goal. When the American College of Financial Services let him know they were primarily seeking a candidate with strong leadership skills, Nichols was elated.

“I thought, ‘Wow this is an unbelievable opportunity,’” Nichols said. “’I could come in and be a college president like I wanted to be, but it would be for a nontraditional school that’s focused in the space that I’ve been in for the last 17 years, which is insurance and financial services.’ It just seemed like the perfect fit.”

On July 14, 2017, Gov. Matt Bevin appointed Nichols to serve on WKU’s Board of Regents. Nichols was sworn in for a six-year term on July 28, 2017.

“He has remained closely connected to Kentucky and actively involved with WKU throughout his career,” WKU President Timothy Caboni said in a press release from July 2017. “His business expertise and professional experience will be incredibly valuable to our board and to me as we embark on a new strategic planning process.”

Nichols said he and his wife have always been proponents of higher education because of the impact it had on both of their lives. The couple has funded numerous scholarships at WKU over the years and donated $100,000 to the Chandler Memorial Chapel in 2009. However, Nichols said he and his wife still wanted to do more for their alma mater.

Leslie Watkins, WKU’s senior director of planned giving, said she first met Nichols and his wife about 18 years ago. Watkins has helped the Nichols family coordinate their gifts to WKU on numerous occasions, so when the couple told her they wanted to make a larger investment than they ever had before, she searched for a program they could get involved with.

“George and CJ shared that they wanted to help young people who came from backgrounds similar to theirs,” Watkins said. “Knowing their story, I just really thought [ISEC] would appeal to them. I had an idea of how much money they wanted to invest, so I put together a written proposal to them suggesting ISEC and the different things that they could do.”

Nichols said he and his wife, both first-generation college students themselves, were astounded by the work ISEC was doing to help low-income and first-generation minority students succeed. They immediately told Watkins they wanted to proceed with their donation to ISEC.

On Nov. 15, the center commemorated the couple’s $1.3 million gift by adding “Cynthia & George Nichols III” as a prefix to its name.

“We actually feel very fortunate that Leslie introduced us to ISEC,” Nichols said. “We recognized that young people of color and of low income that are first-generation students probably don’t have all of the support, structure or resources that we just got lucky to have 35 years ago. We were blown away at the structure and leadership they had put in place, and we knew we would like to be a part of it.”

Martha Sales, the executive director of ISEC, said she met Nichols and his wife when the details of their donation were made public. ISEC’s goal is to help WKU “recruit, retain and graduate students of color,” and Sales said the Nichols’ gift has given ISEC the ability to offer students expanded assistance.

“I thank God for the Nichols,” Sales said. “They don’t just want to give their tens, they also want to give their time. Sometimes when people are givers, others perceive that … they just write checks, but no, the Nichols are invested in the program. The funds benefit us greatly, but I would dare to say even if they stopped writing checks, they would still keep us covered in some kind of way.”

As Nichols continues to experience prosperity from a financial perspective, Nichols said he will continue giving back as much as he possibly can. Nichols has achieved success because of the assistance he received from numerous mentors and friends over the years, and he said the best thing he can do is try to make sure every student at WKU has a chance to succeed.

“Western is a big university,” Nichols said. “But the beauty of it is it’s still small enough to make sure that an individual feels loved and supported. That’s why we have wanted to engage even more in Western. We watch it grow, and we’re excited about it growing, but it’s still small enough to recognize who [an individual] is and help [them], and that’s what we want to do.”

Features reporter Drake Kizer can be reached at 270-745-2653 and [email protected]. Follow Drake on Twitter at @drakekizer_.