‘These Shining Lives’ tells story of women impacted by radium poisoning to stunning avail

September 25, 2017

Amidst all of life’s encounters, one thing remains constant – time. Whether spent waiting, hoping or painting watches, time is a major factor in how we choose to live life. This principle holds constant in WKU’s production of “These Shining Lives,” the 2008 play by Melanie Marnich, which depicts life for four women working in a radium painting company before it was considered hazardous.

Heels clicked in the darkness, echoing throughout the Russell H. Miller Theatre as the story began. Catherine Donohue begins her new job at Radium Dial, painting watches with radium dust, and soon meets Pearl, Francis and Charlotte. The four strike up friendship, but soon along their work journey find their hands mysteriously glowing, bones aching and bodies feeling oddly exhausted. They soon realize these feelings are signs of radium poisoning, and begin a journey of pain, dejection and fervor as they seek justice for their ailments.

The story was cohesive and told in a four-dimensional manner with Catherine as the narrator, which left no questions unanswered. The usage of projections was an effective means of escorting the scene changes and was done so exceptionally, from projecting words of plot development to projecting the Radium Dial logo during factory scenes.

Much of the story employed some sort of dramatic irony, especially in moments in which the factory boss would exclaim “radium actually has health benefits,” to which the audience would laugh, considering the later medical developments around radium and its irreversible effects. However, one constant factor loomed over the audience was the ticking of a clock. It gave off an uneasy vibe that communicated the feelings the women had over their sicknesses directly to the audience.

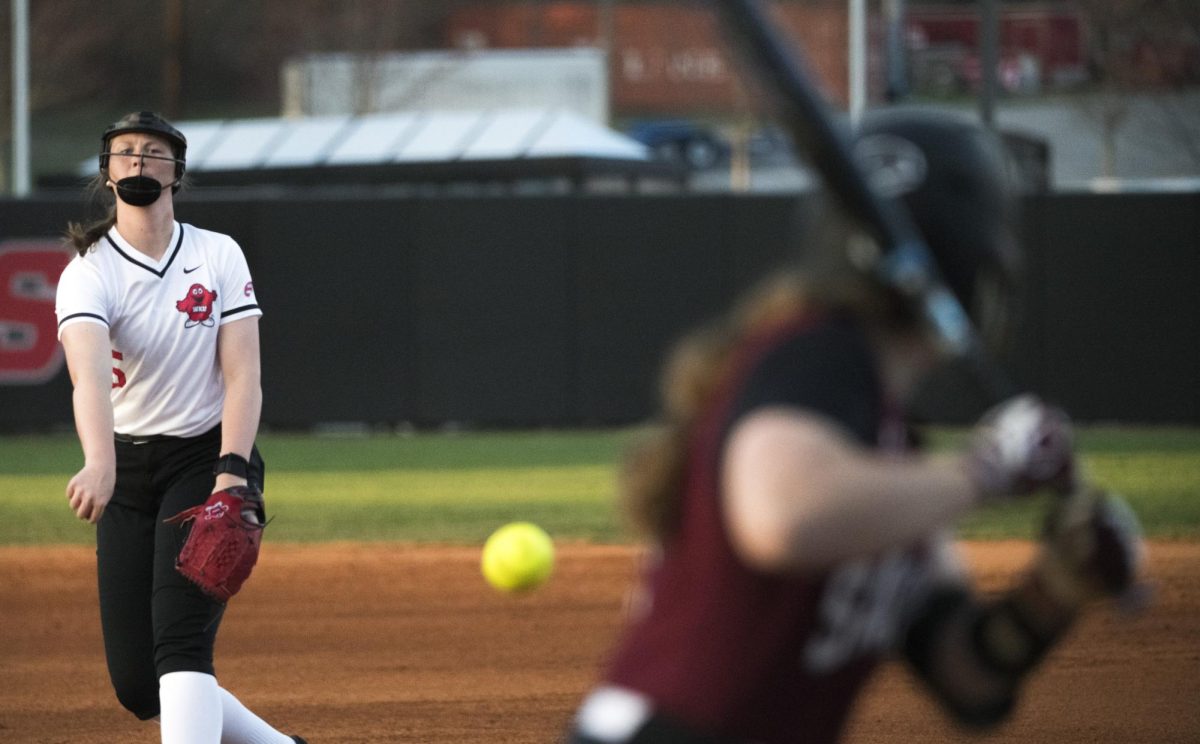

The show’s acting ensemble was dynamic in both chemistry and character development. The four characters in the leading ensemble were each distinct and complemented each other flawlessly. Leading the tenacious ensemble of females was Sabrina Sieg as Catherine.

Sieg had a strong emotional range as the show’s ingenue and fully committed herself to her character’s heavy arc. Complementing Sieg, Lauren Hanson was quippy and unafraid as Charlotte, the factory gossip with a stouthearted demeanor. The show’s quintessential moment arguably came in an encounter between the two aforementioned characters after hearing of their diagnoses. Catherine’s optimistic spirit is struck down by Charlotte’s emotional breakdown in the show’s climactic, and heart-rending moment.

Finishing off the ensemble, Arielle Conrad played the tiresome worry wart, Francis, and had multiple facetious moments that offered a break from the otherwise sober show. Not to be forgotten, however, are the show’s altruistic comedic moments, which came from Emily Huizenga, playing the role of Pearl, the happy go-lucky jokester that lightened the mood of the show dynamically. The show benefitted from the four’s chemistry, which can be a make or break quality in theatre.

From cool blues to stark yellow light, the lighting, operated by Hannah Meece and Sarah Guthrie, effervesced onstage during emotionally visceral moments. The best instance of lighting brilliance was the deep blues that shined on the neon hands of the women during their moment of discovery – an enigmatic moment in the show’s plot. The scenic design was layered delicately, with a building tumbling over the main set to give depth. The main stage area was divided into three areas: home, factory and office. The latter was used for a multitude of office and court scenes. The set design, however, wasn’t divisive, rather each area spilled onto the other, which fit ideally in this show, considering the fluid nature of the storytelling. The sound design, though subtle, helped create the environment through ambient music of the period, along with splashes of ocean waves and radio music.

Alas, the clock struck midnight, and so did the lives of the four women who were impacted detrimentally by the radium they so gaily painted with. The show was a lesson in the dangers in blind belief in life. This ideal was dolefully portrayed incredibly by the WKU Department of Theatre and Dance. Altogether, the performance shined as bright as radium itself, just without the imminent fear of death.

![Megan Inman of Tennessee cries after embracing Drag performer and transgender advocate Jasmine St. James at the 9th Annual WKU Housing and Residence Life Drag Show at Knicely Conference Center on April 4, 2024. “[The community] was so warm and welcoming when I came out, if it wasn’t for the queens I wouldn’t be here,” Inman said.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/smith_von_drag_3-600x419.jpg)