Is corruption the catalyst for change in college sports?

September 29, 2017

It’s official. Veteran men’s basketball coach Rick Pitino is “effectively” unemployed. Apparently, a stripper scandal wasn’t enough.

Fraud and money laundering officially tipped the scale. Along with Pitino, 10 other men associated with college basketball are under investigation. I wouldn’t be surprised if that number tripled by the end of the month.

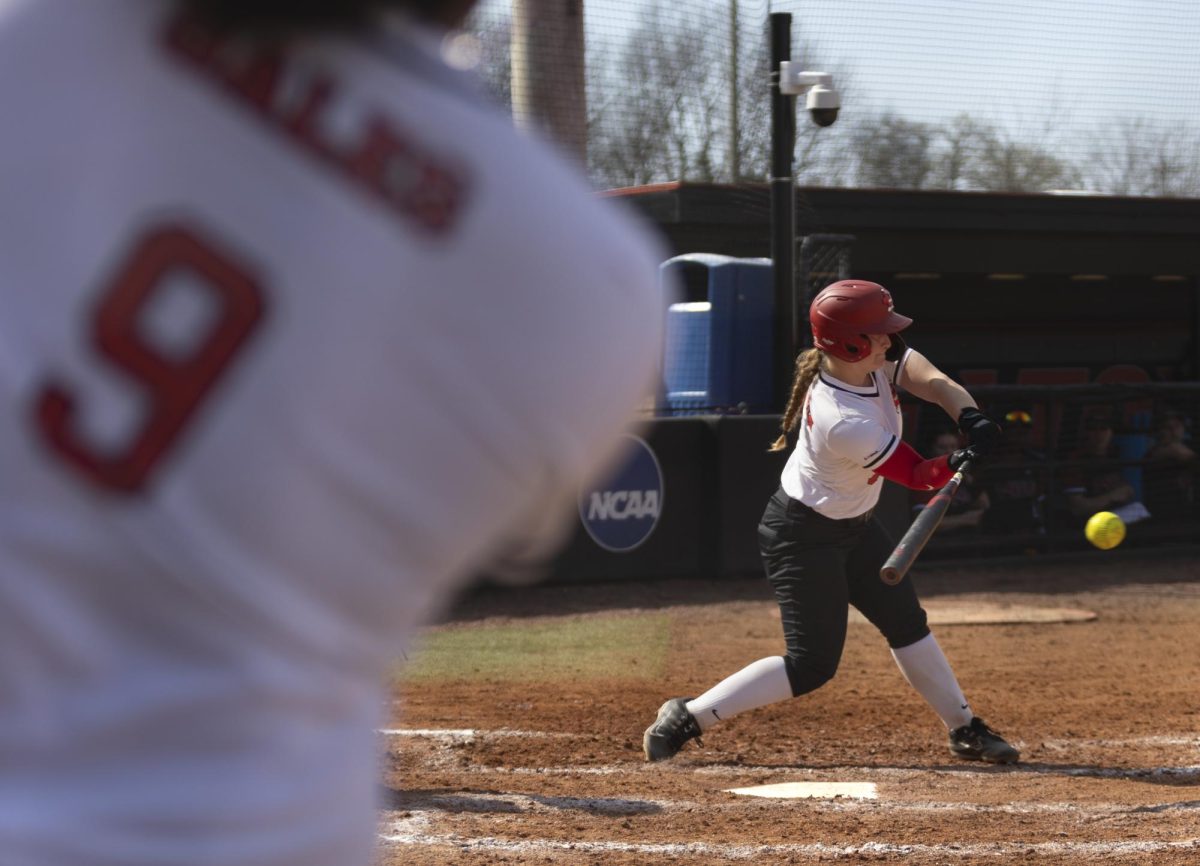

I was a five-year NCAA athlete at WKU and although I loved my team and my sport, I grew increasingly critical of the controlling structure of the NCAA with each passing year. This controversy might help explain why.

The heart of the current controversy lies in the puritan concept of amateur athletics.

To qualify as an amateur, and remain NCAA-eligible, student-athletes are not allowed to accept what the NCAA terms “extra benefits.” The NCAA Division 1 Manual loosely defines an extra benefit as “any special arrangement by an institutional employee or representative of the institution’s athletics interests.”

This vague definition encompasses everything from coaches negotiating multimillion dollar professional contracts to coaches providing their athletes free car rides to and from practices, which is part of the reason Pitino lost his job.

The current fraud case illustrates the necessity of the NCAA to regulate, and consequently over-regulate, illegal benefits. Providing extra benefits, like the $100,000 Pitino donated to the family of one of his athletes, can sway athletes’ decisions, which would effectively give schools with more resources a competitive advantage and keep them in power.

This disproportionately affects the little guys who do not commit these blatant acts of corruption.

This is why college runners can’t accept prize money earned from Turkey Trots and costume races.

This is why the NCAA has barred coaches from charitable work in fear that their donations would reach top recruits, influence their commitment decisions, and thus constitute a recruiting violation (see Kelvin Sampson).

This is why NCAA athletes have been punished for eating “pasta in excess.”

This is why homeless student-athletes can’t accept rent checks from well-meaning boosters.

This is why Michael Oher was excoriated by the NCAA for his decision to play football for the University of Mississippi.

This is why temporarily penniless international athletes arriving in a completely foreign country waiting for their funds to transfer overseas cannot accept money or basic necessities from coaches or boosters.

This is why Shabazz Napier went to bed hungry.

This is why coaches cannot buy their hungry student-athletes food when campus restaurants shut down for a holiday.

This is why approximately 86 percent of NCAA athletes live at or below the poverty line.

Essentially, this is why the true amateur student-athletes can’t have nice things.

Many sports media outlets are predicting the death penalty for corrupt programs, but these scandals may well signal the death penalty for amateur athletics overall.

Corruption may finally be the catalyst that forces the NCAA to finally pay its athletes in an effort to avoid these under-the-table payments.

And, now that he’s out of a job, perhaps Pitino will make like Petrino and coach at WKU next season. Go Tops?