A look into Kentucky’s court-supervised class

May 7, 2017

Under the Microscope

On a rainy Monday in Bowling Green, a crowd of people gathered shoulder to shoulder on the benches of a courtroom in the Warren County Justice Center, awaiting rulings by the judge. Many of the cases on the docket were probation revocation hearings. One by one, a defendant would rise to the stand, get told that their probation was revoked, and leave the courtroom, knowing that jail time was the outcome they would likely face upon trial time.

These sorts of scenes aren’t uncommon in Kentucky, and many in the commonwealth who commit parole (supervision after release from incarceration) or probation (supervision before, or in substitution of incarceration) violations are faced with jail time as a result. In fact, according to 2010 findings by the Department of Corrections, nearly one in five new prison admissions were from technical violations of parole or probation, not from new crimes.

Technical violations encompass failing a drug test, failure to report to the assigned probation or parole officer, failure to notify the assigned officer of a change in address or employment, associating with certain people, being caught drinking at a bar and other factors.

To that end, only about 2 percent of prison admissions resulting from parole violations were from new offenses. Essentially, a large number of ex-probationers and parolees are getting locked up not because they committed a new crime, but because they couldn’t get a ride to the parole office, had trouble finding work, were caught drinking a beer at a restaurant or other reasonings.

Edward Bohlander, professor emeritus of Sociology at WKU, said extensive supervision of probationers and parolees can lead to violations.

“Well, one might say ‘we could increase supervision. We could have more intensive supervision where we force the probationer or parolee to spend more time around the officer assigned to the case and so forth,’ he said.

“But, when you get right down to it, the more time they spend together, the more likely the probation officer is going to see something that’s revocable. So, it’s kind of crazy that when you intensify probation and parole, by definition, it’s going to increase the rate of failure, and that sounds insane but it’s true.”

Like many states, Kentucky has sought to fix jail overcrowding through criminal justice and sentencing reform to keep people who commit non-violent crimes out of jail. Paradoxically, those efforts have created a whole citizen class on probation, parole or other forms of alternative sentencing, many of whom end up in jail due largely to technical violations and lack of graduated sanctions and have exacerbated the overcrowding problem.

A look at prison overcrowding

Prison and jail overcrowding is an issue that faces both the commonwealth and the nation. According to a 2015 report by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with 716 people per every 100,000 behind bars. There are 2.2 million Americans currently incarcerated, due largely to War on Drugs-era policies implemented in the 1980’s and because of the implementation of lengthy mandatory sentencing minimums.

According to a 2015 analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative, if every state in the U.S. was its own country, Kentucky would rank seventh in the world in terms of its incarceration rate. Kentucky’s incarceration rate is 948 people per 100,000 residents, the 11th highest in the nation. There are almost 41,000 people incarcerated in Kentucky, according to a 2015 report by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

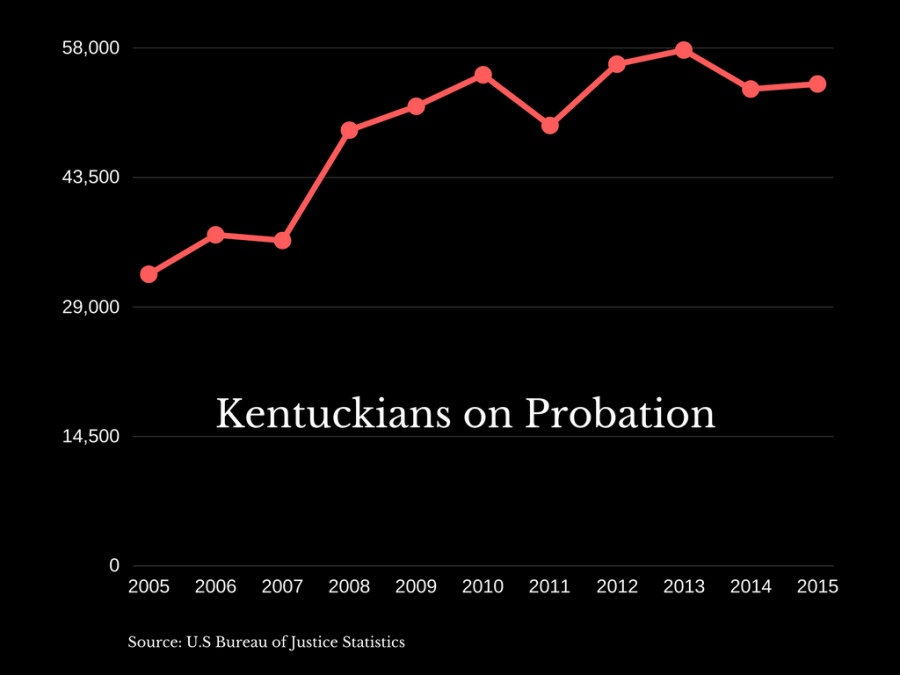

There are approximately 54,000 people on probation in Kentucky, and about 17,000 on parole. The reasons many of these individuals wind up going to jail or prison based on violations vary, with some problems being unique to Kentucky’s systems, while others are intrinsic of the very nature of these systems.

In 2011, Kentucky sought to deter the state’s large jail and prison population in a series of reforms encompassed under The Public Safety and Offender Accountability Act. The law took aim at growing incarceration numbers by focusing resources on high-level offenders, while placing low-level drug offenders on probation and drug treatment programs.

The law also implemented a “Mandatory Reentry Supervision” policy in which a six-month period of supervision is required after release from prison. This allowed for inmates to serve out the last six months of their sentence outside of prison.

The law also instituted graduated sanctions for technical violations of probation and parole, where judges have the option to institute sanctions such as more frequent drug tests or short jail time instead of a total revocation.

However, Kentucky’s inmate population has increased by almost 2,000 since the 2011 law, shattering the expectations of its policies. And though the law addressed the prevalence of prison or jail re-entry due to parole and probation violations by way of graduated sanctions, judges are not required by law to follow them.

Though the 2011 law made steps toward changing aspects of the probation and parole system in Kentucky, these steps still didn’t make it easy for those who must live under court supervision.

Stacy Diaz was once one of these people. When the 39-year-old was arrested for drug charges in 2014, she was given two options: undergo a two-year drug court program full of strict guidelines and requirements, or face jail time. Diaz chose drug court.

A medically-retired Air Force veteran who served for about 14 years, Diaz went through a Veteran’s Treatment Court program in Elizabethtown, Kentucky: a special drug court that deals with the unique challenges of veterans such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Diaz was able to graduate from the program in 2014, and now is an active volunteer at her church and her local Alcohol Anonymous chapter. However, Diaz faced several difficulties while under court supervision.

In the program, Diaz dealt with challenges such as regular mandatory drug tests, a revocation of her driver’s license and a nightly curfew.

With no license and a restriction on how far she could drive, Diaz was forced to go through two years without seeing her children and grandchildren in New Mexico.

“I lost a lot of independence,” Diaz said. “I’m an adult, and I couldn’t travel. I couldn’t go to New Mexico because I couldn’t go over 1,000 miles. So, I couldn’t go see my kids for two years, and my grandkids. So, I had to wait for that. It was real hard.”

These strict guidelines caught up with Diaz once, when she had to spend a short amount of time in jail as a sanction for failing to notify the court of a change of address.

Supervision

Amy Smith, assistant professor of psychology at San Francisco State University and member of several correctional programs and non-profits such as Alliance for CHANGE and Project Rebound, said those living under supervision can find it hard to balance their professional and personal lives with the expectations of courts and assigned officers.

“Stigma and the ways in which involvement in the criminal justice system can create barriers to work and housing are two of the major issues we see,” Smith said. “Sometimes expectations of POs can also create independent problems. For example, I’ve seen students who have lost jobs or failed classes because they are told that their PO is going to come by ‘sometime’ on a certain day, and they are required to be there, despite work obligations or exams scheduled that day.”

Another major factor in supervision of probationers and parolees is the loss of their Fourth Amendment rights, which protect citizens from warrantless searches and seizures. While under parole or probation, one’s assigned officer has the right to subject them to random drug tests and has the right to search their house, car or person. In addition, police officers are not required to produce warrants to search the property of those on probation or parole, if they consult with the person’s assigned officer.

Bohlander cited this as a difficulty for those on probation or parole to adjust to society.

“It’s a matter of judicial grace. In other words, the judge says, ‘I’m going to be really nice to you and I’m going to put you on probation.’ But in order for this guy to get on probation, he’s got to sign away his protections that are guaranteed by things like the Fourth Amendment to the constitution, Bohlander said.

“Often, you’ll find in larger jurisdictions, police use probation officers. If they’ve got somebody who’s out there on probation or parole, they know that person’s got an officer, and they know they don’t have enough probable cause to get a warrant from a judge, they just call the probation officer up and say, ‘Don’t you think it’s time you did a little check on this guy?’”

In addition, some of the requirements of court supervision can run counter to mainstream norms of adulthood. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 52 percent of adults had at least one drink per month in 2013, but Kentucky remains one of the few states in the nation where alcohol use is banned in the baseline requirements of individuals on parole.

Bohlander also pointed to difficulties in finding employment with a criminal record as an obstacle for those on probation and parole, particularly for those who have faced incarceration. According to research by Center for Economic and Policy Research, having a history of incarceration reduces a worker’s chance of being hired by 15 to 30 percent, and reduces the annual number of weeks worked by 6 to 11 weeks

“A lot of [the obstacles for those of probation and parole] are fiscal,” Bohlander said. “A lot of them are an inability to earn a living because what we have done to those kinds of people is that we have labeled them. And in this age and from now on, electronic record keeping systems make it really easy to check on these guys. You can’t just lie anymore on an application and say that you don’t have a prison record when in fact you do or that you don’t have a probation violation or something like that.”

Tackling criminal justice reform

Kentucky’s 2017 Legislative Session has brought about additional changes to the state’s criminal justice system. In late 2016, Gov. Matt Bevin constructed a task force to tackle issues relating to criminal justice reform.

Some of the aspects of the bill include a policy that prohibits incarceration for those who are unable to pay court fines, a policy that provides compliance credit for some on probation and parole, implementation of reentry drug programs for certain inmates and parolees and other policies.

Though some of these policies address issues that those under court supervision face, Bohlander said approaching a successful probation and parole system in Kentucky must be attained through a change in public attitude.

“What we need of course is to be a little less punitive and be a little more transformational in our approach to probation and parole,” Bohlander said. “In other words, we’ve got to help the probationer or parolee make adjustments in their life, but we’ve got to have a world that is willing to accept those adjustments too.”

Smith mirrored this sentiment, saying a change in perception of all players in the correctional process is important for criminal justice systems in all states.

“I think the perception of what a PO is, and is supposed to do, could be shifted,” Smith said. “Rather than viewing these folks as correctional officers, cops, or people enforcing the law and controlling ‘lawbreakers’, instead viewing them, training them, treating them, as counsellors with access to resources and the desire to see their clients succeed, rather than preventing their parolees from committing another crime, for example.”

Reporter Andrew Critchelow can be reached at 270-745-6288 and [email protected].