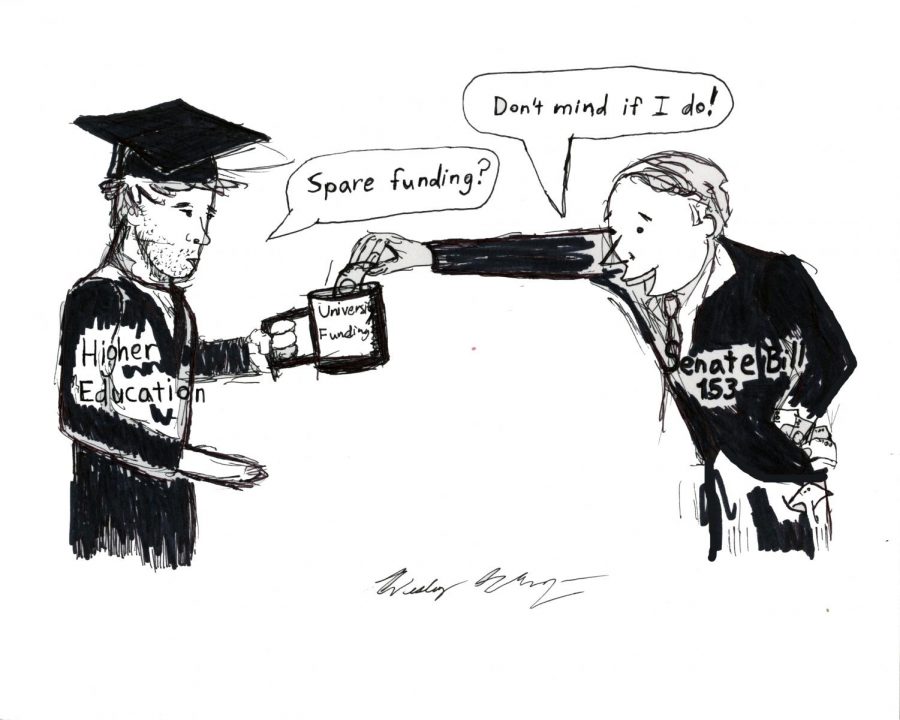

Money Model: Performance-based funding would harm WKU

March 27, 2017

The Issue: With the recent passage of Senate Bill 153, Kentucky will begin implementing a new model for higher education funding based around different metrics of performance and other criteria.

Our Stance: Not only will this model harm WKU, but in the long-run will have negative effects on higher education in Kentucky, and at a time when higher education has been continuously under attack.

Since last year, talk has surrounded a new model of funding for higher education in the state. Kentucky has been looking towards changing state allocations to performance-based models under the vision of Gov. Matt Bevin.

At the last Board of Regents meeting, President Gary Ransdell laid out the blueprint for Kentucky’s new performance-based method for funding public universities.

Here’s an outline of the plan:

Thirty-five percent of allocable resources are distributed to universities based on the number of degrees awarded.

Another 35 percent will be awarded based on the total number of students’ earned credit hours.

The remaining 30 percent of the pie will be distributed amongst universities based on campus facilities, campus administrative functions and academic support services, such as libraries.

The way the model would work is under the current state budget five percent of higher education base funding will be put into a pool. At WKU, this amounts to almost $4 million. So, when you think of the pool don’t think of a kiddie pool, but one with a gold plated slide, platinum encrusted diving board and a boat. Also, the boat has a crew who make $12.50 an hour.

Ransdell was appointed by Bevin as the chair of a workgroup charged with defining the funding model.

Ransdell said, in his 2016 August convocation, the workgroup had formed a model which would “accomodate historic performance, rather than a goals approach which only measures future performance.”

“And that’s good for us at WKU,” he said.

Except, performance-based funding isn’t only not good for WKU, and Kentucky, but there’s large disagreement as to whether or not it even benefits states such as Ohio or Tennessee, which Bevin’s plans have drawn comparisons from.

Starting with WKU, many of the criteria drawn under this plan deals with enrollment and retention. Which is to say, how many students can WKU get in the door and how many can WKU prevent from walking back out. Both are areas WKU has continually struggled with, especially within just the last decade.

Enrollment itself was given as a primary reason for the university’s recent $6.5 million budget shortfall.

Additional metrics underneath the new plan base funding around STEM+H degree production. Yet, WKU has always produced more undergraduate and graduate degrees outside of STEM fields, especially in comparison with the universities of Kentucky and Louisville.

While most states have started to restore higher education funding after the recession, Kentucky has continued to reduce funding, according to a 2015 report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Kentucky has continually reduced state funding for education, placing the financial burden on the backs of students, and now we’re expected to perform well on arbitrary metrics for money that’s hardly available.

Under the new model, there could also be unintended consequences which would have a negative impact on low-income, adult, minority and academically underprepared students, according to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

“While the proposed model does indicate specific metrics for degree attainment for low-income and minority students, the bill does not specify what shares of the funding they will be — and those described in the Performance Funding Work Group report were quite low,” Ashley Spalding writes in the KY Policy Blog.

This comes despite the fact one of the desired goals, as outlined in a 2016 Strategic Agenda by the Council on Postsecondary Education, is to increase the number of bachelor’s degrees earned by underrepresented ministry and low income students.

Additionally, it’s not just Kentucky facing these consequences. States such as Ohio and Tennessee, which have had these sort of performance driven models before Kentucky, have seen problems.

Findings of a 2014 survey of college administrators in Indiana, Ohio and Tennessee conducted by the Community College Research Center found colleges may deal with these funding formulas by using grade inflation or admitting fewer at-risk students.

Weakened academic standards were cited as concerns by respondents as well as the costs of compliance with performance funding, lower morale, narrowing of institution mission and threats to faculty role in governance.

Some of these may already sound familiar here at WKU such as: weakened academic standards, lower morale and threats to faculty role in governance. We doubt implementing a model which has faculty concerned elsewhere about these issues will somehow improve the already existing issues here.

Nicholas Hillman, an assistant professor of education at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, argued in a report published by The Century Foundation that performance models should give schools incentive to support students, but rarely result in positive outcomes.

“While pay-for-performance is a compelling concept in theory, it has consistently failed to bear fruit in actual implementation, whether in the higher education context or in other public services,” Hillman writes.

However, this is now the new reality for higher education in the state. One we believe to be misguided. Our only hope is in three years time when they evaluate the model to ensure there are no unintended consequences that there are, in fact, none.

But our opinion is that not only will this adversely affect WKU, but Kentucky as well.

Ransdell will not be around by the time such evaluations are made, but we believe this decision will be a blemish on the legacy he leaves here.