‘BECAUSE I SAID SO’

There is another side to President Gary Ransdell’s legacy that should be told. The Hill and its people look radically different today than they did two decades ago. The man who rebuilt WKU did so according to his vision — but at what cost?

In August 2015, Gary Ransdell stood onstage in front of a crowd of WKU faculty and staff at the annual presidential pep rally called the Fall Convocation.

Ransdell praised Gordon Emslie, the former WKU provost, who was reassigned to faculty status after five years as the university’s chief academic officer. Few in the crowd applauded as Ransdell articulated Emslie’s “successes.” Some folks cheered a little — why was not clear — and Van Meter Hall remained mostly quiet save for Ransdell’s rolling voice.

A little more than five years earlier, Emslie and David Lee, then dean of Potter College of Arts and Letters, became finalists for the provost job. Emslie got it.

But in 2015, when Ransdell introduced Lee at the convocation as the provost replacing Emslie, the hall erupted in applause.

“Next week, [Emslie] begins his well earned sabbatical before assuming his teaching and research duties as a full professor in physics and astronomy in January [2016],” Ransdell said. “Thank you, Gordon.”

With that, Ransdell ended a five-year Emslie experiment met with faculty and staff disapproval. This moment of sobriety kick-started a year of harsh truths for Ransdell.

In the 2015-2016 academic year, Ransdell faced much: a new governor hell-bent on gutting support for higher education, a $1.4 million dip into reserves to cover a budget shortfall, a $6 million budget cut, a foundation that’s losing money, declining enrollment, grief over insubstantial raises for faculty and staff for the better part of a decade, and a series of annual workplace surveys that show growing dissatisfaction with his leadership.

When Ransdell started as president in 1997, he made $149,000. In 2016, his salary is $427,824.

On Jan. 29, Ransdell threw in his red towel and announced his retirement.

“My last day in office will be June 30, 2017,” wrote Ransdell in his retirement email. “As provided in my contract, I will then begin a six-month sabbatical leave from July 1 to December 31, 2017 — at which time my employment at WKU will end.”

When Ransdell started as president in 1997, he made $149,000. In 2016, his salary is $427,824.

During the past 15 years, WKU spent lots of money growing. But in 2008, the university started getting less cash from the state. WKU started tinkering with admission standards and continued the previous decade’s growth in enrollment. When it comes to the annual budget, enrollment drives revenue.

“We had to create the budget capacity to do things that needed to be done, and 50 percent more students helped create that budget capacity,” Ransdell said.

In 2012, Emslie tightened 2009’s loosened admission standards. Undergraduate enrollment took its first dive in more than a decade, dropping from 18,115 to 17,517. The freshmen class of fall 2013 had better ACT scores, but overall retention hardly changed. Meanwhile, WKU’s “Age of Construction” was peaking. In June of 2012, WKU took out a bond for $35.8 million to pay for phase three of renovations to the Downing University Center. The university’s long-term debts totaled $175.6 million.

Today, faculty salaries fall well below benchmark after eight years of virtually no raises, and a proposed 3 percent increase for the 2016-2017, while a step in the right direction, is just that — a first step. Meanwhile, in-state tuition has nearly quadrupled since 2000 from $2,209 annually to $9,482.

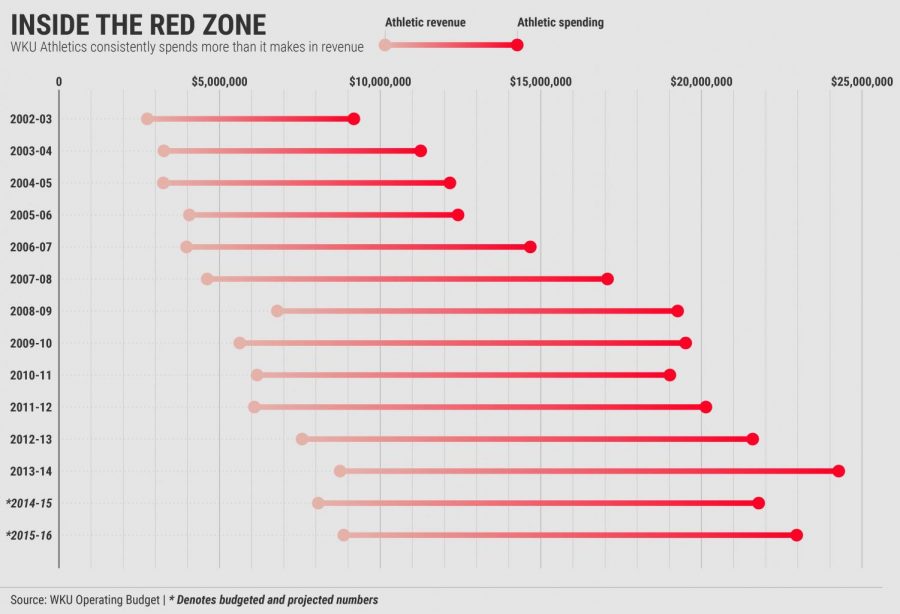

Athletics spending went from $19 million in 2010 to a projected $22.9 million in 2015, WKU budget documents show. The football team’s budget is $6.4 million in the 2015-2016 budget. It includes $500,000 for team travel costs, $2 million for employee wages and $320,394 labeled “Materials — Contingency.”

The football team finished a successful 2015 season, and Head Coach Jeff Brohm got a $200,000 raise — private money, the news media reported. But bottom line: the WKU athletics budget is twice as large as the revenue it produces regardless of the source of budgeted money.

As a living president, Ransdell earned himself a namesake building on campus. The man has a quote engraved near Guthrie Bell Tower alongside quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln. WKU has been celebrating Ransdell’s successes for years. But there is another side to his legacy.

THE NEW MILLENNIUM

In 2000, Ransdell’s fourth year as president, 15,516 students attended WKU, according to WKU’s Office of Institutional Research. Today 20,178 attend. Then, Kentucky residents paid $2,290 per year to attend undergraduate classes. Now they pay $9,482. In 2000, Barbara Burch served as provost. Now she sits on the WKU Board of Regents as faculty regent.

“All of this is not by accident,” Burch told a College Heights Herald reporter in 2000 for an article with the headline “Focus on enrollment and retention starting to pay significant dividends.” The article explained plans to further push enrollment.

“Look at the university’s strategic plan,” she said. “We have goals of our own to increase the number of students.”

In 2000, 58 percent of faculty rated Burch’s provost performance as “poor” or “very poor,” as the Faculty Work Life Survey from that year shows. The same year, the WKU Faculty Senate became the University Senate, which meant stronger administrative control.

Burch stepped down from her provost position 10 years later after a decade of constant growth at WKU. During those 10 years, undergraduate enrollment increased 34 percent to 20,903 students. In-state tuition increased 198 percent to $7,560 per year. Money granted to WKU from state appropriations increased about 18 percent.

The Division of Enrollment Management started targeting that 20,000-student benchmark in 2006. The following year, WKU started selling bonds to pay for construction projects. The university took out $52 million in general receipts bonds in 2007, almost doubling the university’s long-term debt from $67 million to about $115 million. From then on, WKU’s accountants started calling its debts “obligations” on the school’s financial statements.

WKU’s long-term debt now stands at $200 million with a payment schedule ending in 2034, according to the university’s financial statements. Roughly 75 percent of that money is bond debt. For example, transforming Downing University Center into the Downing Student Union added $35.9 million in 2012. Then WKU took out another $36 million in 2013 to build the Honors College and International Center and put the finishing touches on DSU. In 2016, WKU will pay $13.7 million on long-term debt. Ransdell says this debt is low for a university of WKU’s size, but he’s referring to its size after he became its leader and it started to grow rapidly.

“You don’t rebuild the campus without incurring some debt in the process,” Ransdell said.

In 2009, a special President’s Task Force headed by Lee proposed renaming the Bowling Green Community College to the Commonwealth College and recommended admitting some students who did not meet WKU’s admission standards. The task force report noted that, historically, WKU has accepted some students who did not meet admission standards.

Both recommendations eventually took hold. The Commonwealth College later became South Campus.

Some applicants with an ACT score less than 15 gained conditional admission. These students needed to take remedial classes at the Commonwealth College, later South Campus, before they could start earning credit toward a degree program. But here’s the catch; they still paid full tuition. An open records request for records on the number of students let in conditionally through the years was denied because “such documents do not exist,” according to paralegal Lauren Ossello, WKU’s executive legal assistant.

Task force recommendations went into effect in 2010, the same year Burch stepped down as provost. Emslie got the job.

“I think over time, people will come to get to know me,” Emslie told the College Heights Herald after his hire.

They did, and data from the annual Faculty Work Life Survey administered by the University Senate shows that they didn’t like what they learned.

CASH MONEY

The biggest chunk of WKU’s revenue comes from tuition and fees. That “biggest chunk” status used to apply to money from the state. Ransdell usually points to this as an explanation for why tuition keeps increasing.

But a closer look shows that tuition hikes have far outpaced state cuts and did so even before state cuts began. The first big hit came in 2008, when state appropriations to WKU dropped from $83,842,700 to $80,683,800. Tuition costs have increased every year since 2000 — from $2,290 annually at the turn of the century to $7,948 in 2008. Revenue brought in from tuition and fees increased to $97.9 million from just $40.8 million in 2000, a change of 139.7 percent.

Gov. Matt Bevin’s attacks on higher education further increase WKU’s dependence on tuition. WKU already lets in about 93 percent of applicants, so another tuition hike became inevitable for the 2016-2017 academic year. Tuition is increasing another 4.5 percent.

The new Kentucky state budget brought a 4.5-percent cut to state money — a loss of about $6 million.

Professors such as Eric Bain-Selbo, the head of WKU’s philosophy department, are worried that people in the university’s liberal arts programs could lose their jobs.

“The overwhelming majority of the budget is faculty salaries,” Bain-Selbo said when cuts were first being discussed earlier this semester. “When you decide to cut state appropriations by nearly a tenth, you’re not going to offset that by cutting down on the number of copies being made.”

Instead, the financial burden is landing on custodians, diversity programs and 23 other sources around campus. WKU privatized custodial and groundskeeping services through a contract with Sodexo.

Sodexo, an international company with its North American headquarters in Maryland, has faced repeated student protests at universities throughout the U.S. for years. Its work on U.S. campuses inspires organized protests by United Students Against Sweatshops, the organization’s website states.

WKU is keeping its “International Reach” tagline, but it’s also cutting $50,000 from the Office of Diversity and Inclusion as well as $151,000 from the newly combined ALIVE Center and Institute for Citizenship and Social Responsibility.

Sports spending is also taking a hit after years of steady growth, but one team is taking the full brunt of the cut. The track and field team is losing 50 percent of its budget. Students such as junior Jenessa Jackson of Marietta, Georgia, an All-Conference USA shot put competitor on the track team, are now debating whether to transfer or to ride out a final year with a half-axed track program.

“It’s unfair,” Jackson said. “We are the most decorated team on this campus. We deserve an explanation.”

Ransdell said balancing the athletic budget is the responsibility of Todd Stewart, the director of athletics. It’s his decision to make, Ransdell said.

“Track has been a terrific program,” Ransdell said. “Unfortunately, it’s not a program that our athletic department is built around.”

WKU spent more than $20 million annually in recent years to prop up revenue deficits in the athletic department’s budget. Athletics usually generates enough revenue to recoup about one-third of that. For 2015-2016, WKU budgeted $22.9 million for intercollegiate athletics, according to WKU budget documents. It’s projected to make just $8.8 million in revenue — a deficit of $14.1 million.

The biggest source of revenue for WKU athletics comes from “guarantee games” — big payments to WKU from big-time programs that think playing WKU can guarantee a win. This football season, LSU paid WKU $975,000 to play the Hilltoppers, according to public records. WKU lost that game 48-20. The University of Alabama is paying WKU $1.3 million to play the Hilltoppers in 2016. WKU will turn around and pay $300,000 of that to play Houston Baptist University.

Another item on Ransdell’s priority list is the Honors College, one of his prime and costly legacies.

Some programs, such as travel abroad funding, within the Honors College are losing $51,000, a relatively small drop for the program. The Honors College’s budget nearly quadrupled in the last decade from $271,117 to $2.5 million today. The latest WKU Factbook brags that the number of Honors College enrollees increased by 42.2 percent in the last five years from 988 students to 1,405. Now they make up about 8 percent of the total undergraduate student body.

“Most students are on academic scholarships in the Honors College, but again, it raises our academic strength of our campus,” Ransdell said.

The new Honors College and International Center added another $22 million to WKU’s long-term debt.

Space inside the building reserved for the Navitas program — nine offices, a reception room, a workroom and a little sign that reads “Navitas Suite” — is all empty. WKU canceled its partnership with Navitas on Dec. 15, 2015. During the 2015-2016 academic year, two Honors College academic advisers quit, and so did its associate director.