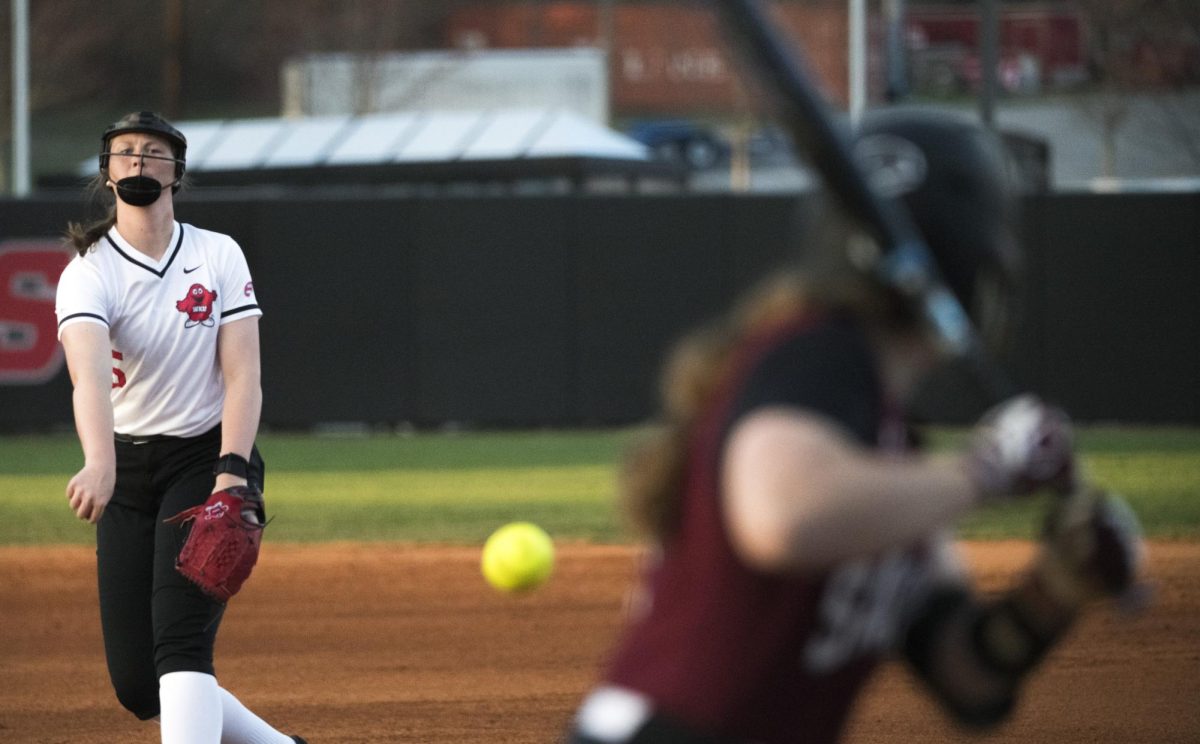

In My Skin: Woman finds comfort in self despite skin condition

May 1, 2014

In My Skin is a weekly feature series that looks to tell the stories of diverse student populations at WKU. Its goal is to serve as a simple reminder that WKU is location of diversity — or at least trying to be.

*****

While in the process of packing to move to a new house last August, Brittany LaRue ran across a decade-old photograph from her high school graduation. In it, LaRue held her cousin and stood by her best friend. Upon remembering the feeling that accompanied this memory, LaRue burst into tears and decided to return to a happier place.

A few months after that photograph had been taken, LaRue noticed the first sign of a condition she would most likely face the rest of her life.

At the time, LaRue wasn’t aware the pale spot on the back of her neck was vitiligo, and she assumed it was a small burn from a perm she had recently gotten. After 18 years with no sign of problems and no family members with the condition, a small spot wasn’t too disconcerting.

The spot only grew a small amount over the next couple of years, but once it grew bigger LaRue decided it was time to have it checked out. Although the biopsy results came back as something different, her doctor realized it was vitiligo.

“He used the example, ‘That’s what Michael Jackson has,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, oh, Michael Jackson is white now so I don’t know what it is,” LaRue laughed.

Besides Jackson, there wasn’t much public awareness concerning the rare condition, but upon learning she had it LaRue began to do her research. With unknown direct causes, the depigmentation of different areas of skin could have been triggered by a variety of internal or external factors.

It can be influenced hereditarily or by mental health such as increased stress, or even the diet of the individual. Due to the unknown nature of the condition, even now there is still no universal cure.

When LaRue’s first two doctors told her they were unable to help, she found other ways to go about her day as the pale spots began to style themselves around her neck.

“I used to go to this store downtown and I would get these hemp necklaces and put them on (to) cover it up,” she said. “If I was at work it didn’t matter because it wasn’t on my hands then, it was just around the front of my neck in little spots.”

As the little spots on her neck grew bigger, LaRue attempted to find alternative methods.

“I spent about $300 on some make-up and I don’t even wear make-up,” LaRue said, adding that she at least received a refund when it didn’t work.

“A lot of those treatments are very expensive. When people are like I was at the time — kind of upset they have it and it’s still new — (you’re) gullible to everything,” she said.”You just want to be how you were.”

The third-time charm seemed to work for LaRue when she went to another doctor in Nashville. From there, LaRue would apply a cream on the spots and receive ten minutes of sunlight a day for six months.

When two rounds and two different creams didn’t have any effect on her skin, she was referred to a specialist (who in turn instantly referred her to a more well-versed specialist) that dealt with light therapy.

In some cases of vitiligo, light therapy has been shown useful with use of high-powered narrow band UVB rays, the opposite of the UVA rays used in some tanning beds.

After set periods of time in the stand-up booth, the lights “reactivate” the pigment in the pale spots. On her first trip to receive the therapy, LaRue was excited the entire drive.

What is it? What’s it going to do? These were the questions that she asked herself when she closed the door, surrounded herself with bulbs as tall as the cylinder itself. These were the only questions she had time to ask.

“I was only in there for 30 seconds. I drove all the way to Nashville for 30 seconds,” LaRue said. “But I burnt. Thirty seconds and I was pink because it was such a high powered bed.”

With the new therapy, LaRue found herself alternating between driving the required three trips to Nashville a week, going to class part-time at WKU, and working full-time. After awhile, lack of time, gas prices and insurance co-pays began to take their toll and she was forced to stop attending the thrice-weekly visits. However, LaRue said the visits were worth it and didn’t concede treatment options all together.

“It started getting expensive,” she said. “I was thinking ‘I’m going to have to go get a tanning bed package,’ and that’s what I did.”

Through her research of local tanning beds, LaRue found that some basic tanning beds emit the type of ray needed for her skin. In the meantime, LaRue is saving up for an at-home light-ray therapy device.

Throughout this 11-year journey, LaRue had been search to find something that would allow her to network with others in similar circumstances. Last year, she found a conference in Florida the week of her birthday in August. In the months leading up to the conference, LaRue was still covering her spots with things such as short-sleeved turtlenecks for summer, in turn replaced by necklaces.

It was in the few weeks leading up to the conference that 28 year old found herself glancing at her past self in the form of a graduation photo.

“I found a picture of graduation and I just started bawling. It wasn’t because I was all brown, it was because I looked happy,” she said. “That’s where I needed to get back to.”

Accepting the fact she had been depressed about her condition the whole eleven years, LaRue started taking steps to be happier. When she attended the conference a few weeks later, LaRue decided she wasn’t going to cover any of her spots.

“I’m with people just like me,” she said. “There’s no sense in covering up.”

From attending the conference, LaRue found there was more awareness now about vitiligo than there was when she was first diagnosed. Many presenters discussed various treatments, one included traveling to Jerusalem for a three-week treatment in which cream is applied, preceded and followed by a quarter-hour bathing session in the Dead Sea.

The conference was part of a turning point for LaRue, especially after seeing the amount of children who attended.

“That’s probably one reason I thought, ‘What am I over here complaining about?’ I’m an adult at least,” she said. “These are kids that have to deal with other kids who are probably bullies. A lot of them had it worse than I did.”

Since becoming more comfortable in her skin, LaRue has looked for opportunities to further vitiligo research and awareness as well as turning down opportunities for a fundraiser to send her to Jerusalem.

Krystal Beel, LaRue’s friend of almost 20 years, said she’s been by her side since day one.

“I can say I’m here for you, but I don’t understand firsthand how it feels to have those looks and those comments made,” Beel said, adding that she’s proud of LaRue for becoming more comfortable.

“It’s almost like she’s been set free,” she said. “I told her ‘I’m so glad you’re seeing what I’ve always seen.”

Now 12 years into her journey, LaRue is returning to nursing school at WKU in the spring and hopes to do something in the area of vitiligo research. She was recently chosen as a vitiligo star for the month of April at online vitiligo community, and is currently taking steps to encourage Kentucky to be another state in recognizing June as Vitiligo Awareness Month.

“I think I’m just going to keep it, I think I kind of like it now,” she said. “It kind of makes me who I am now. It’s been there for almost twelve years now, it’s just a part of me.”

![Megan Inman of Tennessee cries after embracing Drag performer and transgender advocate Jasmine St. James at the 9th Annual WKU Housing and Residence Life Drag Show at Knicely Conference Center on April 4, 2024. “[The community] was so warm and welcoming when I came out, if it wasn’t for the queens I wouldn’t be here,” Inman said.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/smith_von_drag_3-600x419.jpg)