Freshman Gordon devoting basketball career to twin brother

October 25, 2011

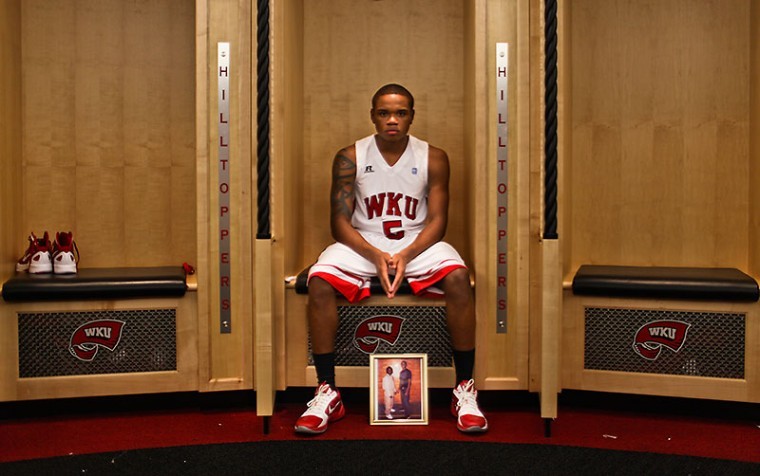

Derrick Gordon keeps a photo of him

and his fraternal twin brother Darryl in his dorm room. In his

locker at Diddle Arena sits another, similar picture of the

two.

It’s how the star freshman keeps his

mind focused on his brother throughout the day.

“When I look at that picture, I just

kind of sit there and think, and I get emotional,” he said. “I know

he could have been at the same place that I’m at playing basketball

and going to school, and it’s not happening because of the

situation he’s in.”

Derrick has dedicated his basketball

career to Darryl, who was put in prison at the age of

16.

In May 2009, an incident arose in a

Plainfield, N.J., neighborhood between Darryl and another man.

Derrick said another neighborhood kid had been “picking on” Darryl

for several weeks, making fun of him for things like his short

stature, and it hit its boiling point on this particular

day.

The other man knocked Darryl’s hat

off his head, not fearing any retaliation from Darryl, even though

Derrick said Darryl had a temper problem.

The other man showed a knife, so Darryl pulled out a

gun and shot the man several times in his chest from point-blank

range.

It required him to have open heart

surgery, and Derrick said he’s still not sure how the man

survived.

Darryl was arrested and charged with

attempted murder and sentenced to five years, one month and six

days in prison.

Derrick received the news during

basketball practice when he was 16 years old.

“I was shocked. I was just stunned,”

he said. “It was just hard to believe because my family isn’t in to

all that — violence and getting arrested and stuff like

that.”

When Derrick takes the court this

season in his first year at WKU, he’ll don No. 5 — the number his

brother wore when he was a basketball player.

On the left side of Derrick’s chest

is a tattoo that reads “M.B.K.,” which stands for “My Brother’s

Keeper.” On the right inside of his arm reads another that says

“HOPE and FAITH,” and on the left side reads “FAMILY

FOREVER.”

Derrick said Darryl is his main

source of motivation and is what drives him to work harder each

day.

“I’m basically just working hard and

trying to make it to that next level so that when he gets out, he

has something to come home to,” Derrick said. “Everything I do

right now is for him — on and off the court.”

Derrick’s dream was for his

basketball career to continue with Darryl’s. In middle school,

though they were both still young and underdeveloped, it looked as

if that might be a possibility. Derrick said he and Darryl started

receiving interest from the same colleges about

basketball.

Derrick’s father, Mike Gordon, said

Darryl, a point guard, was the more athletic one of the two when

they were both younger, and it stayed that way for a

while.

“I would tell the school that the

only way I’m coming is if he was coming,” Derrick said. “At the

same time, Western Kentucky was looking for a point guard. It could

have worked out real perfectly.”

But several things changed once the

two got to high school. Derrick grew to 6-foot-3 while Darryl

topped out at 5-foot-5.

Derrick grew into a quiet, somewhat

introverted personality while Darryl became more outgoing, Mike

said.

The biggest change came when Derrick

said he wanted to go to St. Patrick High School instead of

Plainfield High School where Darryl was going.

Derrick was attracted by St.

Patrick’s nationally-regarded basketball program. In the past five

years, three St. Patrick players were named McDonald’s

All-Americans and went on to play at major Division I college

basketball programs Duke, North Carolina and Kentucky.

At first, St. Patrick’s basketball

coach Kevin Boyle wasn’t on board with Derrick’s

decision.

“He came as an eighth grader and he

was dying to go to St. Pat’s. Personally I didn’t think he was good

enough,” Boyle said. “He called, and called, and called, and

called. He was always a hard worker and had a lot of self

confidence in his game.”

But Derrick enrolled at St. Patrick.

It was the first time he and Darryl had ever really been separated

for a long period of time.

Darryl continued his basketball

career at Plainfield High School, but never reached the level of

success that Derrick experienced.

Darryl began trading his practice

time for other activities. He got mixed up with a rough crowd and

started hanging out on the streets.

Mike Gordon said he and his wife

Sandra started blaming themselves for Darryl going down the wrong

path.

“As a father it’s like, people are

always giving you credit for the good job you’re doing with the

kids when they do well,” he said. “On the other side, they tell

you, ‘We know you did everything you could. It’s not your

fault.’

“But then it’s like, how could you

take credit for the positive stuff, but not take the blame for the

negative stuff?”

Derrick put blame of what happened

to Darryl on his shoulders.

“I tried to talk to him, but I

didn’t talk to him as much as I could have,” Derrick said. “I could

have done a lot more to prevent the situation, but things happen

for a reason.”

Derrick had trouble opening up to

people in the aftermath of it all. The heartache that he was

feeling about missing his brother was kept bottled up

inside.

“I stayed to myself,” he said. “I

just didn’t want to talk about that whole situation because it hurt

me so much inside.”

Derrick then went through a three-

to four-month period when he wasn’t eating enough. His mother

Sandra didn’t call it depression, but said he was visibly hurting

and lost a lot of weight.

The teachers at St. Patrick had no

idea what was causing it.

“No one knew,” she said. “I went

there one day because the guys wanted to talk to me and I just had

to come out with it. Then Derrick — that’s when he really started

to open up. I always told him if you talk about it, you’ll feel

better.

“They were real close. They did

everything together. It was like taking half of him

away.”

Boyle said it got so bad at one

point that Derrick considered transferring from St. Patrick to

Plainfield High School to be closer to home.

“To his mom’s credit, she made him

stay,” he said. “That was a life-changing decision for

him.”

Derrick eventually got to visit

Darryl, and they exchanged letters back and forth. Once that

happened, Derrick slowly regained the weight he lost.

And when he finally saw Darryl

again, Sandra said his face “lit up.”

“He just smiled,” she said. “They

just laughed and talked and he was just so happy. After that he

went on to school and things just started getting better for

him.”

Fast forward to Derrick’s senior

year of high school at St. Patrick. He had already signed his

National Letter of Intent to play at WKU, but this was still a

chance for him to make a name for himself.

After what Boyle called a “horrible”

preseason, Gordon responded with 37 points against Chicago’s

Whitney Young High School at the City of Palms Tournament in Ft.

Myers, Fla.

Derrick emerged as one of the key

players on St. Patrick’s team last season, the second leading

scorer behind Michael Gilchrist.

But there were times throughout the

season when thoughts of Darryl would creep back into Derrick’s

mind. Boyle had to balance being a tough coach while also being

understanding of the fragile emotional state that Derrick found

himself in occasionally.

HBO made a documentary on St.

Patrick’s 2010-2011 season entitled “Prayer for a Perfect Season,”

— set to air Tuesday — and Boyle said there’s a scene that shows

him trying to make that balance, although it could seem a little

harsh because only a clip of the conversation was shown.

His message was that while he and

the team understood what Derrick is going through, they still had a

job at hand — to win basketball games.

“One day you’re going to go to work

and your boss is going to feel bad about something in your life,”

Boyle said. “But at a certain point, you need to be accountable to

him and the rest of the team, or they just can’t carry you if you

can’t handle it.

“It was that type of message. We

can’t keep putting you on the court if you’re not

producing.”

Gordon has now had a few months to

get acquainted with Bowling Green, which is roughly 850 miles from

his home in Plainfield, N.J.

He hasn’t seen his brother since

May, and he’s not sure when he’ll be able to next. Darryl moved

from a youth correctional facility in Bordentown, N.J., nearly two

hours from Derrick’s home to South Woods State Prison.

He knows he’ll see him eventually

and is counting the days until Sept. 30, 2014 — the day that Darryl

is set to be released from prison.

But until then, Derrick’s life and

basketball career are focused on what his brother last said to

him.

“He just wants to see me succeed,”

Derrick said. “He knows how badly I like to win and how bad I want

to get to the next level. He told me that, no matter what, just

stay focused and play hard.

“When he told me that, I stuck by

it. Now I’m just on a mission right now. I’m sure a lot of people

see that.”