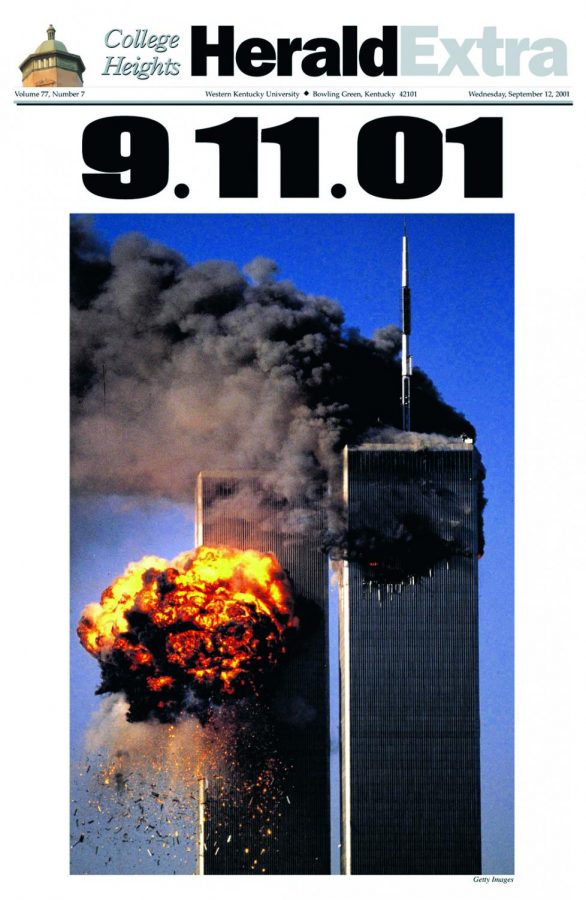

‘It breaks my heart’ — Stories from the Sept. 12, 2001 Herald

September 11, 2011

Editor’s note: The following is a republished version of the main story that appeared in the Herald’s Sept. 12, 2001 extra edition.

Within one hour yesterday morning, three hijacked airliners crashed into the World Trade Center Towers in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington D.C., tearing open two of the nation’s icons and setting them afire.

It’s the worst act of terrorism the nation has ever seen.

As the smoke rose and the dust cleared, America began to search for her lost and for her answers.

In a small town more than 600 miles away, Western’s community was doing the same.

We responded with shock. We responded with tears. We responded with prayer.

Here are our stories:

Amber Douthit refused to leave her room. She was afraid the phone would ring and she would miss it.

But she was more afraid of what the person on the other end of the line would tell her. She’d been in tears since she first heard about the terrorist attacks.

At 5 p.m. yesterday, Douthit, a Henderson sophomore, was waiting on news from Washington. Her aunt Gina works at the Pentagon and was still unaccounted for.

“I’m hoping she’s just lost in a throng of people and being herded somewhere or helping out,” Douthit said. “That’s the type of person she is.”

She got online and found a layout of the Pentagon. She thought she located her aunt’s office in the defense department, but she didn’t look any further.

“I’m too afraid,” she said.

Douthit skipped two of her three classes yesterday to stay by the phone.

“I’m just in shock. I can’t fathom how someone could do this to all the families,” she said. “I’m sure they have families and I don’t see how they could be so cold-hearted, how there’s so much hate.”

Douthit’s father died just over a year ago and she prayed her family wouldn’t have to go through losing someone again so soon.

She tried e-mailing her aunt and calling her cell phone and apartment. But all she could do was wait and pray.

At 10 p.m., the waiting was over. Douthit got a phone call from her mother who said her aunt was safe. She had been on an assignment at the time of the attack.

“I feel like I can breathe again,” she said. “But I still hurt for the other families.”

* * *

Normally, associate journalism professor Harry Allen decides when his Editorial and Feature Writing class will be over. It’s supposed to last from 2 to 4:15 p.m. Yesterday he let the students decide.

Allen talked for 10 minutes, and then told the half-full class that they could stay and discuss the day’s devastation as long as they wanted, but he wasn’t having class.

They stayed for more than an hour. Some wanted information. Some wanted answers. But mainly they wanted to talk.

Madisonville senior Julie Gibson said she’d been waiting all day for this class. She wanted to know what Allen would say.

Gibson recounted her day for the class, starting with her drive to campus when she first heard of the events on the radio.

“I couldn’t help but just start bawling,” she said.

Allen’s students offered comparisons for the event, trying hard to find an appropriate corner for it in their heads. The Oklahoma City bombing. John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Pearl Harbor.

But they couldn’t find a match.

Bowling Green senior John Collins was frustrated.

“We had an identifiable opponent in Pearl Harbor,” he said. “But now we don’t know who it is. We don’t know.

* * *

She was concerned about her son.

As news of the attack spread, Western’s School of Journalism and Broadcasting director Jo-Ann Albers’ attention from shock to panic.

Her son, 42-year-old U.S. Navy Commander Stephen G. Albers, attends weekly meetings at the Pentagon.

Stephen Albers, who was commissioned by the Navy in 1980 after graduating from the University of Michigan, helps oversee the special military installation in Washington where the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other government officials seek shelter in the event of an emergency.

“I was very concerned when I heard about the attacks,” Jo-Ann Albers said. “But I decided to send him an e-mail. I though the last thing he would need to hear at a time like this would be to hear his mother was trying to call him.”

Her son was en route to one of his meetings yesterday. But Albers received a prompt e-mail response and was relieved to hear he was safe.

He was at the north gate of the Pentagon and could see the smoke coming from the building. He was asked to turn his car back and head away from the premises.

Jo-Ann Albers suspended her 9:30 class yesterday and was visibly shaken as she watched television news coverage with her students.

“I’m sure what’s going on in my Journalism 301 classroom was being replicated in many other classrooms,” she said.

* * *

Students clad in a mismatch of pajamas, and school clothes huddled around the big-screen TV in the lobby of Rodes-Harlin Hall to watch the billowing smoke roll off the crumbling World Trade Center.

On the dorm wall hung a bright orange sign. On other days it might have held information on upcoming events. But this wasn’t any other day.

“How do you feel about the terrorist attacks in D.C. and New York?” the sign read.

On the floor below it sat a bucket of markers for students to scrawl their feelings.

“It’s scary to think our nation, the world power can be so vulnerable,” one anonymous message read.

“Anger, Vengeance, Sorrow,” another read.

Some students wrote to help heal wounds — theirs and others.

“I just thought I should write because if someone sees what I think, maybe they’ll know what they think is okay,” said Denise Fox, a freshman from Murfreesboro, Tenn.

Amid the grief, Rodes hall director Tehanee Ratwatte sat with her staff at the front desk checking in residents as they came into the lobby.

She advised residents and staff on how to handle their grief.

“Talk about it,” Ratwatte said. “Talk to professionals and after a while you need to get yourself away from it. Go for a walk, listen to music, play the guitar, do whatever you need to do to get rid of your stress.”

* * *

He couldn’t believe what he had just heard.

Armando Arrastia was in a meeting yesterday when his secretary broke the news.

The World Trade Center, where Arrastia had worked for eight years, had been attacked. He entered a state of disbelief.

“I’m just shocked,” he said. “I’m not a real emotional person and I’m emotionally drained.”

Arrastia, a Western alumnus, is the director of publications and web services for the Department of Education in Frankfort.

He worked at the World Trade Center as a spokesman for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Almost 10 years after leaving that position, he’s still close to many people who were in the towers yesterday morning.

“I can only assume the worst,” he said. “I’ve been praying all morning. It breaks my heart.”

Arrastia realizes what the worst can be. His first job at the center was on a anti-terrorism task force. He said no one ever imagined a plane would hit the building.

When he began his job in media relations, Arrastia worked on the 68th floor of the center. When he saw the first footage of the planes striking the towers, he thought they hit above his former floor. He remembers the building taking hours to evacuate.

As the buildings crumbled, he lost hope that his former co-workers made it out.

Arrastia said he could picture his friends: sitting at their cubicles between gray partitions, on the phone or writing press releases.

“I can’t believe people would do this to other people,” he said.

Sitting in his office in Frankfort, Arrastia knows he’s blessed that nothing like this happened while he was in the building. He tries not to focus on what-ifs.

“If I had stayed there, could it have been me? Maybe, but I don’t think like that,” he said.

Instead, he’s thinking of those he may have lost.