Judicial Affairs monitors on- and off-campus misconduct

April 15, 2011

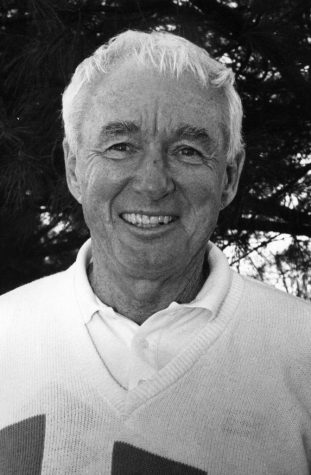

Get arrested for alcohol intoxication or get caught plagiarizing, and you’ll probably find yourself seated across from Michael Crowe, the director of Judicial Affairs.

“I’m the judicial umbrella for WKU,” Crowe said.

Judicial Affairs, located in Potter Hall, has only been around for about three years, Crowe said. It was formerly the Dean of Students’ office.

The office routinely checks crimes reported in the WKU police media log or any warrants, arrests, citations or indictments reported in the Bowling Green Daily News for student misconduct.

They also deal with on-campus offenses, most commonly academic dishonesty. Crowe said there’s an especially large amount of plagiarism cases at the end of the year.

Crowe said he thinks Judicial Affairs has become well-known in the campus community.

The process begins when Judicial Affairs receives information about a student violating the Student Handbook.

First, the office contacts misbehaving students about meeting with Crowe, he said. Students have 48 hours to respond before getting an academic hold — or a knock on the door.

“We don’t want someone to slip through the cracks,” he said. “…It’s just me and them. It’s a chance for them to tell their side of the story.”

Crowe said he reviews the Student Code of Conduct regarding the violation and sets consequences and “behavioral expectations” for one year.

“They’ve already gone through this,” he said. “We don’t want it to be double jeopardy.”

If the violation is serious enough, the student will appear before the University Disciplinary Committee, a court of 13 faculty, staff and students, Crowe said.

In the most severe cases, a student may be expelled and have a violation marked on his or her permanent record, he said.

Because of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, students aren’t required to share information about proceedings with parents or guardians in most cases, he said.

Special Operations Capt. Kerry Hatchett, who works with campus police, said students probably feel more comfortable telling their side of the story to Judicial Affairs than to campus police.

“They help get to the bottom of what really happened,” Hatchett said.

Campus police gives any information about citations, criminal activity or traffic stops involving students to Judicial Affairs, he said.

Hatchett sometimes goes to Crowe’s office directly about projects or student issues.

“I have a real good working relationship with him,” he said.

Howard Bailey, vice president for Student Affairs, helped create Judicial Affairs and still assists Crowe with cases occasionally, sometimes covering for him when he’s out of town.

Bailey thinks Judicial Affairs is doing well after three years.

“It (the office) helps develop students’ integrity, character and citizenship,” he said.

History professor John Hardin, who’s the chair of the University Disciplinary Committee, said the committee only gets the cases that are referred to them by Judicial Affairs.

“It’s set up like a conference, where we all sit down and look at the evidence, which is technically called a finding,” he said. “After that we determine a sanction.”

The most severe sanctions are expulsion or suspension from school, but that rarely happens, Hardin said. Examples of suspendible or expellable misconduct are using a weapon on campus or multiple drug or alcohol offenses.

Judicial Affairs is designed to give every student a fair hearing and make campus a safe education environment, he said.

Students can appeal the committee’s decisions, but it takes a lot of work, he said. The amount of cases the disciplinary committee gets varies each year.

“Sometimes we get one, and sometimes we get a lot more,” he said. “In the end, we’re trying to protect 20,000 students.”