The lasting impression of Dero Downing

April 8, 2011

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was originally written in 1999 by former Herald staffer Travis Mayo, now an assistant attorney general in Frankfort. Dates and information have been updated as much as possible.

Dero Downing was in his family’s barn, milking the cow, when his mother walked in about 73 years ago. She came with a visitor, WKU basketball coach E.A. Diddle, who had one thing in mind. Diddle, who went on to become one of college basketball’s winningest coaches ever, sat on a bale of hay, and the mother left her son and the coach alone.

“Somebody told me you’ve been down to the University of Tennessee to try out,” Diddle told Downing then.

Downing told the coach he had visited the school.

“They can’t do anything for you down at the University of Tennessee,” Diddle said. “Hell, they’re not able to suit you. You come to Western.”

And that’s where Downing went in 1939, on a basketball scholarship.

He never left.

Before red and white

Downing was born on Sept. 10, 1921, in Fountain Run. His family moved to Tompkinsville, then to Horse Cave. That’s where Downing grew up, with six siblings — James, Elizabeth, Alex, Joseph, George and Sarah. By high school, he knew he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his basketball coach by becoming a math teacher and a coach. Downing was on two Horse Cave teams that went to the state tournament, including one with his older brother, Alex, in 1937.

That athletic ability brought Downing to WKU in 1939. He was a member of the late Diddle’s first basketball team to play in the National Invitation Tournament in New York’s Madison Square Garden. By 1942, Downing was a starting guard.

The lasting impression was beginning to take form.

The reality of war

The games finished after Downing graduated with a degree in mathematics in the summer of 1943. His country needed him. Downing joined the Navy in the midst of World War II. On D-Day in 1944, he was there as an officer on a Landing Ship Tank carrying troops and supplies in the first wave to hit the Normandy beaches.

That day on Omaha Beach taught the 23-year-old Downing a lot about life. What he saw changed him forever.

“The experience itself — you never want to have to go through again — but it taught you a lot in terms of the importance of unified effort toward a common goal,” Downing said. “It was a time when people, almost without exception, had a great sense of devotion to country — patriotism. And no one ever questioned why.

“The people I served with were tremendous,” he said.

The group of 12 crewmen aboard LST 515 gathered annually for reunions decades after the war. One such reunion was scheduled for September 1998 in Nashville, but Downing had to cancel because a health problem flared up. He got a card from his friends instead.

“We’ve had a bond of friendship that has continued through the years for a number of years,” Downing said. “There’s a kind of bond of respect and friendship that keeps us together like a giant rubber band. When you go through what we went through, you get kind of close.”

He was part of a high-scale rehearsal for D-Day called Exercise Tiger. It and other rehearsals had been necessary because the projected landings on Normandy would be different from anything previously attempted. Downing’s LST 515 was the exercise’s lead ship, because it carried the chief officer of the convoy, Commander Bernard Skahill. Exercise Tiger turned into a disaster on April 27, 1944, when German ships spotted the Allied vessels and opened fire. The torpedoes hit, and 749 men were killed.

“It was unexpected,” Downing said.

He was officer of the deck early the next morning, from 4-8 a.m. HIs watch log reads, “0435, approaching burning wreckage at various courses and speeds. 0445, commenced lowering boats to pick up survivors. 0735… Underway various courses and speeds en route to Portland, England, with approximately 118 survivors, 14 litter cases, 45 dead.”

LST 515 had been ordered, like all the convoy’s ships, not to stop for survivors. But Downing said the captain of his ship, Lt. John Doyle, wanted to save lives. Doyle was a chief quarter aboard a destroyer that was sunk at Pearl Harbor.

“He was determined that if there was anyone out there that survived, we were going to try to pick them up,” Downing said.

Exercise Tiger was forgotten by many for a number of years, but not by those who were there for the disaster in the water.

“It was probably the most emotionally-filled experience,” Downing said.

He served across the English Channel until the end of the war. He was released from active service as a lieutenant in late 1945.

From battlefields to the Hill

The young Downing was still in his uniform when he showed up again at what is now WKU. C.H. Jaggers, then-director of the College High and Training School — a campus laboratory school — gave the soldier his first job. Downing became a coach and taught math, just like his old high school mentor. After 10 years, he was named director of the training school.

That’s when Mary Sample met Downing. His secretary for decades, she first filled in for Downing’s secretary at College High a couple weeks during the summer.

“Everything was ship-shape and in good order,” Sample said of the school under Downing. “You didn’t see anybody out in the hall.”

Downing became the university’s registrar in 1959. Three years later, then-president Kelly Thompson named Downing director of admissions. He was the dean of business affairs from 1964-1965, then took the administrative affairs vice president position when it was created in 1965. He served in that position until becoming WKU’s fourth president in 1969, replacing Thompson.

He had reached the top of the Hill he had devoted his life to.

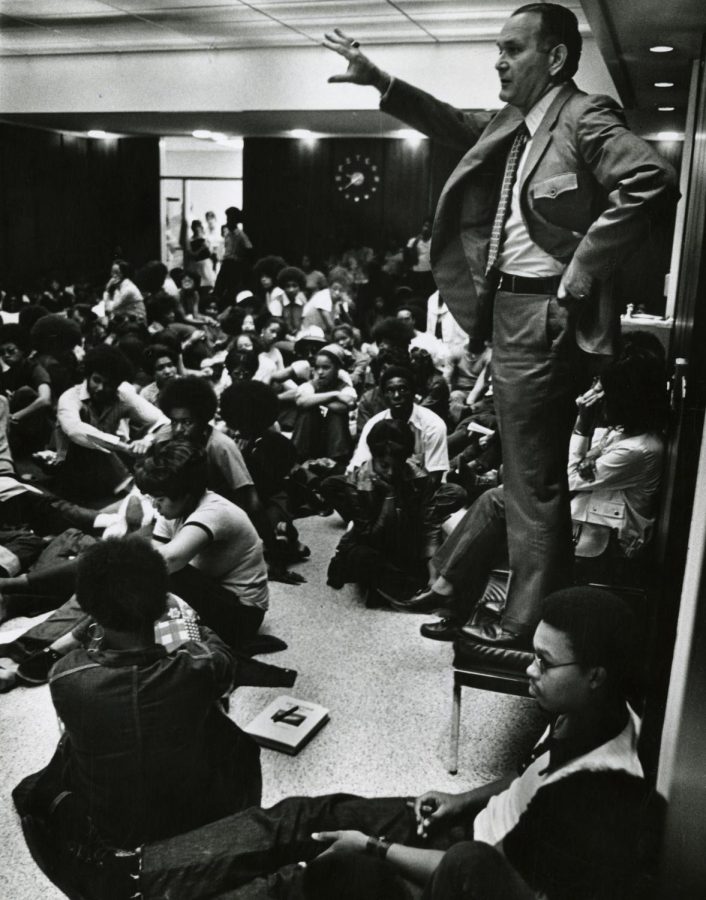

During his 10-year tenure, Downing could often be found mingling with students, or bringing them into his office to talk about the tough choices of life. And while he started the routine before becoming president, Downing always stopped to pick up trash while walking on campus. It was something he never gave up.

“I’ve always felt that a big part of a student’s education is to make them aware of the importance of small things — orderliness, cleanliness,” Downing said. “I don’t think any of us want to be embarrassed by a trashy campus.

“I certainly never did consider myself too good to go over and pick up a can or a piece of trash.”

He was also close to WKU athletics. Former Hilltopper football coach Jimmy Feix said Downing’s athletic background made him more interested in WKU sports. That made Feix stay on his feet more, because he knew Downing knew what was going on, Feix said.

“He saw athletics as a vehicle for promoting the academic welfare of the university,” Feix said. “But he made sure athletics stayed within its place.

“He utilized sports as just a window through which people could see our university but not let that window be the whole wall.”

In 1978, Downing surprised many by announcing his intention to resign as president. He said he felt that repeated health problems wouldn’t allow him to give the right amount of energy to the job.

Downing ended his five-page statement to the Board of Regents with tears rolling down his face.

He apologized for crying that day, which was the day before he turned 57. He wanted to make sure he didn’t receive more credit than he deserved.

“What little any single individual might do is relatively small,” Downing said.

Downing became president of the College Heights Foundation and began helping students with financial needs.

“There’s a human interest story behind practically every one of them,” he said of the foundation’s more than 500 scholarship funds. “Because so many of them are to honor some group or some individual, some family.”

Downing parked his 1979 Pontiac station wagon, faded wooden panels by 1999 — but spotless inside — in front of his office every day. He picked up any trash he saw on the way in.

A family man

Harriet Downing has always been at her husband’s side. She met Dero her first day at WKU on a Thursday in the fall of 1941. They had a date the next Monday. The couple married in 1944. Through 67 years of marriage, Harriet never thought about taking a back seat to Downing and his professional world.

“Dero always made me feel that what I did, I could do better than anyone else could,” Harriet said.

That included raising five children — all WKU graduates — and 13 grandchildren. Then there were the morning phone calls from Downing, telling his wife they would be having company for lunch, and the frequent dinners for Downing’s basketball teams.

“She deserves stars in her crown for having been such a wonderful wife for 55 years,” Downing said in 1999.

The couple’s children — Dero, Anne, Elizabeth, Katherine and Alex — were part of that crown. Alex was close to his father every day since 1996, working in the College Heights Foundation.

“He has always been my greatest role model, and I think it’s because of his undying loyalty to Western,” Alex said in 1999. “I’ve learned so much. What’s so great is being able to draw on his experience and his knowledge of the university and higher education.”

Alex was there with his brothers and sisters when his father was president, cleaning parts of campus on Sunday afternoons. Downing would spot the remnants of a party on the way to church and draft his children for a cleanup after lunch.

“They never did much like going across campus with me, because I’d point to something and they’d get it,” Downing said.

But they usually did pick it up. It’s a family love for WKU that runs past the father. It’s been there for quite awhile.

“We used to walk downtown to a movie after we became seriously involved,” Harriet said. “We’d walk back up State Street and talk about, ‘Someday, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could come back to Western,’ not ever realizing that it would happen like it did.”

Western was his life

Downing had seven different jobs at WKU.

“Any position I had, I never did view it as anything other than where I was going to be the rest of my life,” Downing said. “And doing the very best job that I could do, whatever position I had.”

Downing also received a master’s degree from WKU in 1947; was awarded the Ed.S. degree by the George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville in 1958; was awarded the honorary Doctor of Humanities degree by Kentucky Wesleyan College in 1970; was awarded the honorary Doctor of Laws degree at Murray State’s 1974 commencement; was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Humanities by Morehead in 1974; and was awarded the honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Eastern in 1979.

He left a huge impression on WKU. He left the same on education.

And for now-president Gary Ransdell, Downing left an impression on him. Ransdell was a student and then an employee during Downing’s presidency.

“He’s meant a great deal for several generations of students,” Ransdell said. “He’s served Western in many different capacities and all of them have been beneficial to Western.”

John Oldham, former WKU basketball player, coach and athletics director, said Downing loved WKU as much or more than anybody he’d ever met.

“‘The Spirit Makes the Master’ — he exemplifies that,” said Oldham, also a long-time friend.

The legacy

Downing once said he had a “great feeling of love for this school” and that he wanted WKU to prosper.

The legacy Downing left behind is likely to never be erased. More than just a building with his name, there will always be a part of Dero Downing on the Hill that was his home.

![Students cheer for Senator at Large Jaden Marshall after being announced as the Intercultural Student Engagement Center Senator for the 24th Senate on Wednesday, April 17 in the Senate Chamber in DSU. Ive done everything in my power, Ive said it 100 times, to be for the students, Marshall said. So, not only to win, but to hear that reaction for me by the other students is just something that shows people actually care about me [and] really support me.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/jadenmarshall-600x422.jpg)