Behind The Cameras: WKU photojournalists on what it meant to cover 9/11

Provided by WKU Photojournalism

James Kenney and David Cooper stand on the streets of Lower Manhattan in New York City sometime during their trip documenting the devastation caused by the attacks on the World Trade Centers on Sept. 11, 2001.

September 11, 2021

Most people alive in 2001 can recall the moment they first heard the news. For photojournalism professor James Kenney, it was different.

“We kept one eye on the news, and one on things here and had to keep going on,” Kenney said.

With no immediate threat at WKU, everyone went about their day, keeping up with the news as best as possible. Kenney’s classes weren’t canceled and his routine continued with a somber undertone.

“I don’t have any specific memories [of that day’s classes], I think you just kind of go into autopilot and you realize that you have to keep going,” Kenney said. “I don’t think it’s a matter of trying to get back to normal as much as it is dealing with it.”

He was approached that morning by several photojournalism students asking if they should go up to cover the events themselves.

“I just said ‘this is something that’s a personal choice on your part,’” Kenney said. “You have to decide whether you’re gonna go, but you need to be prepared.”

He estimated that nearly 40 students went to New York City to photograph the aftermath of the towers’ collapse. Roughly 20 students went to Washington, D.C. Those that stayed in Bowling Green reported on the situation from a local perspective.

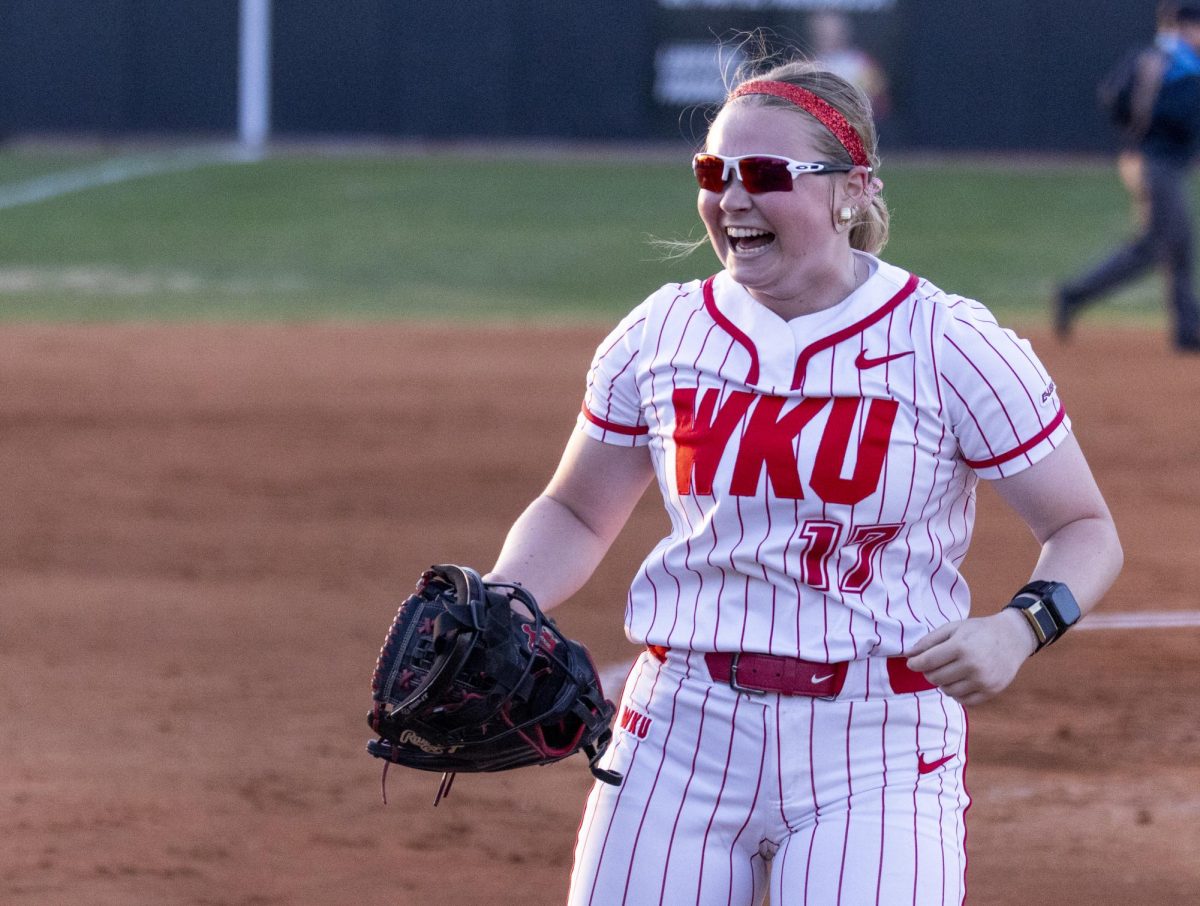

(Jed Conklin/Western Kentucky University)

(Jeremy Lyverse/Western Kentucky University)

Jed Conklin was working for the College Heights Herald when the attacks occurred. He held a number of positions, eventually landing as photo editor in 2001.

“On the morning of the 12th, we left for New York City,” Conklin said. “We had heard rumors that the city was completely locked down, but we made the trip anyway. We had a job to do.”

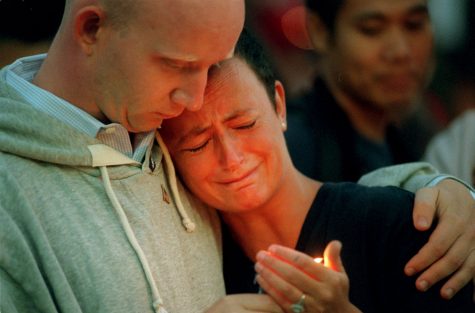

Conklin immediately noted how eerily quiet the city was.

“It was like a funeral,” Conklin said. “Despite how quiet it was, there were thousands of people crowded together in parks, grieving and consoling each other.”

Conklin and his team took a different approach in covering the event, focusing more on people’s experiences rather than the tragedy itself.

“Very few people had accepted that their loved ones were dead. They expected their family members to walk through the front door the next morning,” Conklin said. “That was the hardest part of talking to these people. People were so far removed from reality.”

It was a difficult piece to write. Emotions were running high for Conklin during his time in New York; the true weight of the attacks didn’t hit him until after he had returned to Bowling Green to complete the story.

“Going to the dark room and actually examining the photos I took was the most emotional part to me,” Conklin said. “Just seeing those faces; it’s devastating.”

Like many journalists, Conklin’s objective detachment put a barrier between him and the harsh reality that many faced in the aftermath.

“You have to put on a certain kind of armor to put out the best story you can,” Conklin said. “Because of what we did, the people of WKU were able to get a view of the tragedy they may not have seen before.”

Kenney received the opportunity to go to NYC later that week. He took with him colleague David Cooper. The duo headed up to the city, which they remember as a morbidly interesting experience.

“By the time we had gotten up there, it was an interesting and very sad time, because I think the reality was setting in that people who had been found yet were never going to be found, but you had a lot of people still we’re holding out hope of course,” Kenney said.

They also noticed the overwhelming desire of the victims to have their stories told.

“They only open up to you if they trust you. I do my best to tell that story,” Kenney said. “I feel really privileged, even though I was with these people at a really difficult time in their life, that I could be there on some level.”

He believes that the greatness of photojournalism is the ability to capture intimate, compelling moments in people’s lives, like those showcased in the wake of the attacks.

“Obviously I wasn’t family and wasn’t clergy, but I, in my own way, can tell their story in a unique way that nobody else could,” Kenney said.

Decades later, he believes it’s important to remember nationwide tragedies like Sept. 11, but people should take care not to dwell too long.

“I think that’s healthy, to a point, to look back on it,” Kenney said. “You don’t want to obsess, but I think it is healthy to look back at the past once in a while and remember it; to honor the stories we make as journalists.”

News reporter Michael Crimmins can be reached at michael.crimmins416@topper.wku.edu. Follow him on Twitter @michael_crimm

News reporter Jake Jones can be reached at jacob.jones408@topper.wku.edu.