WKU, individual defendants file responses in Wilkins lawsuit

The WKU Title IX Office on November 29, 2021, shortly after Wilkins’ termination.

May 13, 2022

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include a pair of exhibits referenced in the university’s memorandum of law that were not initially provided to the Herald.

WKU and the individual defendants named in the April lawsuit filed by former university Title IX Coordinator/General Counsel Deborah Wilkins entered formal responses on Thursday evening.

The documents, submitted by Gregg Hovious, WKU’s outside counsel from the Louisville law firm Middleton-Reutlinger, include a memorandum from the individual defendants in support of their motion to dismiss, a memorandum of law from WKU in support of its motion to dismiss and a general answer from the university in response to the plaintiff’s complaint.

Memorandum of Law

WKU’s memorandum of law explains the university’s actions in regards to Wilkins’ employment, confirming the hostile relationship between WKU President Timothy Caboni and Wilkins depicted in the original suit.

Wilkins was originally brought on as WKU’s general counsel in 1994, growing into the role during the presidency of Gary Ransdell, who served as the university’s ninth president from 1997-2017.

According to the memorandum, “after being denied a pay raise,” Wilkins demanded that Ransdell extend her a “protective employment agreement” that allowed her to reach retirement age. The memorandum states that Wilkins drafted an “exceptionally favorable employment agreement” that limited the university’s ability to terminate her for the following reasons: disbarment from the practice of law, a felony conviction, a deliberate refusal to perform her job duties or a refusal to accept reassignment.

The memorandum states that the employment agreement was approved by the Board of Regents at the recommendation of President Ransdell.

According to the memorandum, Wilkins was immediately hostile towards Caboni once his presidency began in 2017. The memorandum states that her behavior and comments to co-workers indicated that Wilkins “did not respect Caboni professionally or personally.”

The memorandum states that in fall of 2018, the university used the services of a third-party consulting firm to evaluate WKU’s leadership team, which included Wilkins.

The memorandum asserts that the evaluation, referred to as “Exhibit A”, found Wilkins lacking in in “people leadership”, with one comment from an evaluator stating that Caboni and the WKU community would be “much better served to seek an attorney who agrees with his vision, promotes community and provides a high level of service to his office. He [Caboni] does not need the drama that Deborah Wilkins brings to her position.”

The full evaluation can be read below:

According to the memorandum, in October 2019, Caboni was informed by two senior administrators that they thought Wilkins was monitoring their email accounts. Since Wilkins served as general counsel and was tasked with responding to open records requests, she was the only person – “other than the IT Department” – with this kind of access.

According to the memorandum, Caboni requested a query of all email searches made by Wilkins from the previous two years, finding that Wilkins had been searching for Caboni’s email account “on virtually a weekly basis over a six-month period” as well as searching accounts of other administrators and cabinet members “on a regular basis.”

Additionally, the memorandum states that Wilkins made 15 open records requests relating to her own person between December 2020 and February 2, 2022. According to the memorandum, WKU produced nearly 34,000 pages and 4.7 gigabytes of data to Wilkins. The memorandum labels these as “harassing requests” and references a letter sent to Wilkins from General Counsel and interim Title IX Coordinator Andrea Anderson summarizing the requests.

“Since December 2020, the University has produced in excess of 33,945 pages and nearly 4.7 gigabytes of data to you,” Anderson’s letter reads. “While the University will will continue to meet its obligations under the Open Records Act and respond to good-faith requests, the University cannot continue to tolerate requests sent with the apparent intention of disruption.”

The full letter can be read below:

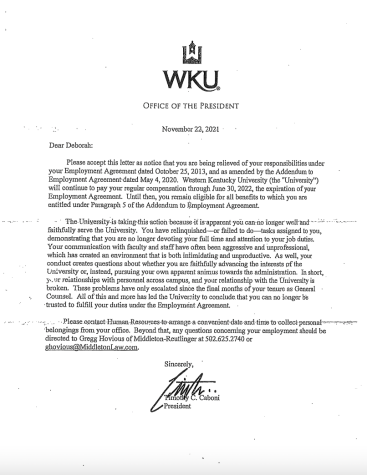

The memorandum states that by November 2021, Caboni “concluded that Wilkins could no longer effectively serve out the remainder of her employment contract” because she had become too disruptive and “could no longer be trusted.”

According to the memorandum, after Wilkins was removed from her office, WKU found a file that Wilkins had begun preparing in early 2020 – “at exactly the time she was searching the President’s emails” – that included personal information about Caboni, detailed, turn-by-turn directions to his out-of-state property and research on his siblings. Additionally, the memorandum states that the university found other files that indicated Wilkins was preparing to sue WKU, such as a detailed timeline that appeared to be the early workings of a draft complaint, among other items.

The memorandum states that Wilkins had become “obsessed with harming the President personally and professionally” and was spending on-the-clock time preparing and researching a lawsuit against WKU.

In its memorandum of law, WKU asks the court to dismiss counts 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11 and 13 that were claimed in the original lawsuit. Additionally, the memorandum asserts that Wilkins’ claims for punitive damages in count three should be dismissed “for failing to meet the applicable statute of limitations.”

In count one, Wilkins alleges that her employment contract was breached when it was not extended for an additional four-year term. “Plaintiff’s breach of contract claim is premised on an oral or implied contract to extend her employment contract, WKU is entitled to governmental immunity,” the memorandum states.

In count three, Wilkins asserts a claim for retaliation in violation of the Kentucky Whistleblower Act. Wilkins seeks compensatory damages, punitive damages and attorneys’ fee under the Whistleblower Act. According to the memorandum, her claim is “barred as a matter of law” because she did not bring the claim forward within 90 days of the alleged claim.

Count four states that Wilkins was retaliated against by the university “based on her opposition to conduct and practices she perceived as violations and/or participation in investigations and other proceedings.”

The suit states that Wilkins engaged in “protected activity” throughout her employment at WKU, which included her “good faith reports and disclosures” regarding Title IX, regulatory and legal violations.

The university’s memorandum states that count four must be dismissed because “all of the alleged protected activities detailed in paragraph 103 of the Complaint indisputably fall within Plaintiff’s job duties.”

Count six of Wilkins’ suit asserts a claim for wrongful discharge against WKU. “However, WKU is entitled to government immunity on this claim,” the memorandum states.

Count seven states that Caboni made “certain material representations” to Wilkins in regard to the buyout of her contract with the university, and that these representations were false. The suit states that Caboni “either knew them to be false, or the representations were made recklessly.”

The memorandum states that since the count claims fraud, the plaintiff would be required to “allege sufficient facts to establish she justifiably relied upon the fraudulent statement or representations forming the basis of the claim.” The memorandum states that Wilkins “has not and cannot allege facts that she justifiably relied on those states for two main reasons.”

The first reason given is that Wilkins’ employee agreement contained a provision that indicated the WKU Board of Regents would need to approve “all employment agreement terms and contracts.” Secondly, the memorandum states Wilkins was “well-aware” that a potential buyout of her contract would require approval from the board.

Count eight asserts a claim for “tortious interference with a contractual relationship.” The memorandum states that this claim fails because Kentucky law requires the party to be interfering with the contract to be a third party to the contract.

Count 10 asserts that the defendants placed Wilkins “in a false light before the public” by the release of her separation letter, and that this false light would be “highly offensive to a reasonable person.”

The memorandum states that Wilkins’ complaint “fails to allege that the letter was published to a third party, a required element of a viable false light claim.” The memorandum goes on to state that WKU is entitled to governmental immunity for intentional torts, which would include false light.

Count 11 alleges that WKU falsified the “Request to Modify a Position” in WKU’s Interview Exchange system and the Electronic Personnel Action Form when Wilkins became Title IX Coordinator.

Wilkins alleges a “negligence per se claim,” which criminalizes the falsification of business records with the intent to defraud. However, the law requires evidence that WKU had committed fraud. The memorandum states that Wilkins “fails to allege that she took any action in reliance on the purported falsification of the two forms.” The memorandum also states that WKU is entitled to governmental immunity on this claim.

Finally, count 13 asserts that Wilkins suffered emotional distress “as a result of the conduct of the defendants,” and that this stress has been severe.

The memorandum states that Wilkins’ claim fails, “as a matter of law,” because none of the alleged conduct is “so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency….”, citing Humana of Kentucky, Inc. v. Seitz (1990).

Individual Defendant’s Memorandum

The individual defendant’s memorandum asks that counts 7, 8, 10, 11 and 13 be dismissed, as well as 5 and 9, which are not mentioned in the university’s memorandum of law.

Individual defendants’ memorandum

The individual defendants in the suit are as follows: WKU President Timothy Caboni; Phillip Bale, chair of the WKU Board of Regents; David Brinkley, the elected staff regent and director of Educational Telecommunications at WKU; Susan Howarth, executive vice president for strategy, operations and finance; and Tony Glisson, retired director of human resources.

Count five, like count 10, also deals with Wilkins’ separation letter, claiming defamation. The suit states that the statements made by Caboni in the letter are “false and were made with reckless disregard for the truth.”

The defendant’s memorandum states that Wilkins’ complaint fails to allege that the letter was published to a third party, “a required element of a viable defamation.”

Count nine of Wilkins’ suit also alleges wrongdoing in regards to her contract buyout, stating that defendants Caboni, Howarth, Glisson, Brinkley and Bale “all had specific knowledge regarding the falsity of Caboni’s statements and were complicit in carrying out the scheme to terminate Wilkins from her position as General Counsel.”

The memorandum goes on to restate the two previously given reasons why Wilkins would be unable to allege facts that she justifiably relied on Caboni’s statements regarding her buyout.

The memorandum’s conclusion states that Wilkins’ complaint should be dismissed for “failing to state claims against the Individual Defendants” because each defendant is protected by the doctrine of governmental immunity.

Defendant WKU’s answer to plaintiff’s complaint

The university’s answer to Wilkins’ suit offers line-by-line responses to the claims made in her initial complaint.

WKU denies the assertion in paragraph 10 of the suit that Wilkins “provided all legal advice and representation to WKU, its officials, and Board of Regents.”

WKU admits that a January 2019 meeting between Wilkins and several “high level administrators” took place, but denies all other claims made in paragraph 25, including the assertion that Wilkins was subjected to verbal harassment and that one administrator asked Wilkins: “Are you going to run to daddy?”

WKU admits the allegations found in the first two sentences of paragraph 27. These include that one administrator from the meeting referred to Wilkins as a “gender-specific obscenity” in the presence of both subordinate employees and members of the community. WKU denies all other claims made in paragraph 27, which includes the assertion that no action was taken toward the administrator in question.

WKU admits to the allegations contained in paragraph 32 regarding discussions of a potential buy-out of Wilkins’ contract, but denies that the allegations to the extent of the discussion constituted an “offer.”

WKU admits to the allegations contained in paragraph 33 as they relate to electronic communications. Wilkins describes that Caboni stated WKU would pay her for one fiscal salary year, payable on July 1, 2020 and amount equal to two years of salary on January 1, 2021.

”Defendant states the communications speak for themselves and Defendant denies the summarization and characterization to the extent they differ from those communications,” the answer states.

WKU admits the allegations contained in paragraph 67, which includes the assertion that Caboni had not met with Wilkins after May 2020.

WKU denies all allegations contained in paragraph 76. The paragraph claims that Wilkins, in January 2022, found that her university email account had not terminated as she had believed, and that WKU officials “had maintained her email account and were reading messages sent to Wilkins.”

The university’s response goes on to address the counts presented by Wilkins, including counts two and 12, both of which were not covered in either the defendants’ or university’s memorandums.

For count two, the university denies allegations 90-92, which read as follows:

That Wilkins was replaced by a significantly younger person; that WKU routinely grants contract extensions for similarly situated male employees with employment contracts, and has done so for the past 30 years; that the conduct of WKU in terminating the employment of Wilkins was in violation of the Kentucky Civil Rights Act.

For count 12, WKU denies paragraphs 144-149 of Wilkins’ complaint, including that Wilkins did not have a legal title to property in her office, WKU refused to allow Wilkins to receive her property from her office and that WKU’s conduct was the legal cause for her loss of property.

The document closes with a list of demands from defendant WKU, including that the complaint be dismissed with prejudice.

Co-Editor-in-Chief Debra Murray can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @debramurrayy.

Co-Editor-in-Chief Jake Moore can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @Charles_JMoore.