Bluegrass Dharma

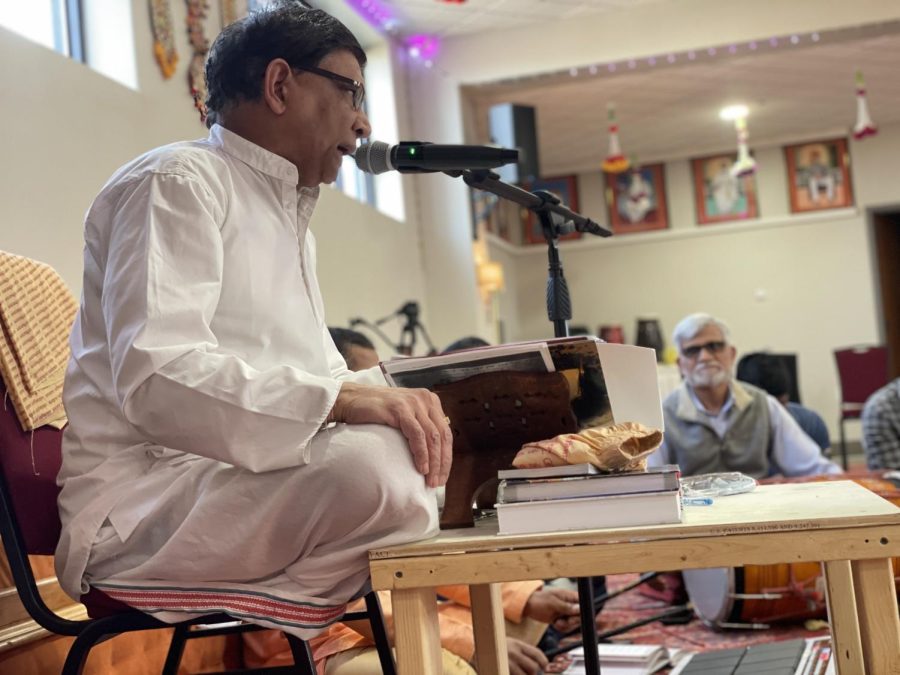

Nick Patel rings a bell and makes final offerings for the night, bringing Ramanavami to a close on March 3, 2023.

Worshippers in the Shree Swaminarayan Hindu Temple hang “Happy Birthday” balloons as the smell of incense and spice fill the air. They are not for a person, but a god — Lord Rama.

Ramanavami, held on March 30 this year, is the Hindu celebration of the birth of Lord Rama, held annually in temples across the world. This is the first Ramanavami celebrated in Bowling Green since the temple opened in 2022.

One by one, devotees kick off their shoes and file into the temple, stopping by a framed image of the god that sits within a cradle.

Each drop rose petals on the seat, rock it by a string and bow with a prayer. Candy and cupcakes are laid at the altar as gifts.

Intricate statues of watchful gods stand all around them, some carrying trinkets or posed as if to bless their subjects. Lord Rama stands tall and straight, pinching a rose and holding an archer’s bow, with balloons strung above him.

Donations are collected in aluminum pie tins, each containing a small handmade wick of frozen oil. As devotees throw bills in, they wave the smoke in their faces as a blessing.

Attendees recite in bhajans — devotional songs — through the night, stopping mid-way for an all-vegan dinner. Then, they dance.

The women form a circular chain, gliding and moving in unison to the music, colorful saris billowing left and right. The men hop and raise their hands, the crowd growing thicker and faster as more guests finish their meals and join.

It is nearly 10 p.m. now, and the music dims over the speakers. Worshippers pick up instruments and pass around tambourines, much to the delight of the children weaving through the crowd.

More bhajans, starting slow and swelling to a roar of voices and drum beats that one feels within their bones. They are building to the exact time of Lord Rama’s birth.

It comes, and cheers ring out from the crowd. A large standing basin is brought out alongside a pot of saffron and water. In the basin stands an infant Rama made of gold, rose petals laying at his feet.

Devotees form a long line and take turns decanting the liquid over the statue’s head, then return to singing and dancing in the crowd. A man with the calloused feet of a religious pilgrim rings a bell and offers a final offering from a conch shell.

The guests take their time exchanging goodbyes, many staying late into the night, but soon wandering back outside. Every celebration must come to an end, even the birthday of a god.

Across town, away from the music and festivities, Ram Pasupuleti sits at his desk, working late as he often does. While unable to attend the festival, Pasupuleti carries a constant reminder of Lord Rama with him — his name.

Pasupuleti acted as a prominent advisor when the temple was only a vision. His dedication to education and cultural exchange has made him an “unofficial spokesperson” in many temple matters.

Born in India, Pasupuleti moved to the United States after marrying his wife, Kavita, in 1996. As she was already a U.S. citizen, Pasupuleti received his green card and moved to the U.S. to further his pain management education.

In Hinduism, Pasupuleti said, a man’s life is divided into four periods: Brahmacarya, studious education and preparation for the future; Grihastha, marriage and career building; Vanaprastha, retirement and charity; and finally Sanyasa, renouncing all worldly possessions as one leaves our reality.

“That transition [to grihastha] is anxious for everyone, but everybody has to make it some time or the other,” Pasupuleti said. “I did make that transition and fortunately for us, it’s worked out, and my wife and I are still here.”

Pasupuleti soon found himself in New York, working as a researcher at Long Island Jewish Hospital’s psychiatric facility.

The U.S. began seeing a steady increase in Indian-born immigrants at the time, a trend that continues to this day. In 1990, around 450,000 people born in India resided in the U.S., according to the Migration Policy Institute.

By 2000, that number had grown to over a million, and by 2021, surpassed 2.7 million.

Pasupuleti says immigration requirements were much looser in the ‘90s prior to post-9/11 legislation. In addition, since Kavita was already a citizen, he was automatically entitled to conditional residence.

Still, Pasupuleti said, he hesitated in accepting citizenship. At the time, India did not recognize dual citizens, meaning Pasupuleti would have to choose between his homeland and his new home.

“I did not accept the citizenship of this country for a good 10 years, simply because it’s not easy to do that —- to relinquish the country where you’re born,” Pasupuleti said. “It’s a very, very, thoughtful process and you have to think about it.”

Things changed in 2005 when new legislation in India made dual citizenship possible. The decision became much easier for Pasupuleti, and he became a full citizen in 2006.

By then, Pasupuleti had a daughter named Rachana, who was around five years old. Since 1998, they had been living in Lubbock, Texas, so he could train at Texas Tech University.

“[Working in New York] gave me access to many different clinical training routes in this country,” Pasupuleti said. “I found out the best pain management program in the world was in Texas at that time, and so that’s why we went there.”

Pasupuleti spent five years training in Texas and received several job offers before being scouted by a small private practice in Louisville, The Pain Institute, eager to pick up someone from such a prestigious school.

He had the option of staying in Texas or moving to Kentucky, a decision he weighed as heavily as any other. Being the researcher he is, Pasupuleti pulled out a map and got to work.

Pasupuleti wanted to be near family, as he had been with his in-laws in Texas. He drew a circle around Louisville, a radius of around 150 miles, and found that 6 or 7 family members lived nearby, some in Louisville and most in Ohio.

Next, Pasupuleti observed what he calls the “Snow Line” — the area roughly north of Cincinnati that experiences much higher snowfall than the rest of the country on average. Louisville fell just below the line, to Pasupuleti’s pleasure.

Finally, Pasupuleti hoped that a smaller practice may offer him better opportunities, and with that departed for Louisville. He worked for six years, but grew weary of the structure around him.

“I was way too independent for group practice,” Pasupuleti said. “With group practice, you have to practice what they want you to, but I’ve always been someone who is independent and thought for myself.

The idea of his own pain management practice had always appealed to him, so he began researching the potential of starting from the ground up. But Louisville had several practices, and finding his market would be a challenge.

North of his “Snow Line” was off the table, so he began looking south.

Several connections in Bowling Green told him there was great potential for practice in the area. At the time, only one major pain management center called the city home.

In addition, he and his wife wanted someplace quieter, slower — specifically, with better traffic, he said.

“Anywhere in the city, I could get there in 10 minutes,” Pasupuleti said. “It’s not like that anymore, but it was like that when I came here.”

He knew of maybe two Indian families in Bowling Green, one of which was preparing to move to Louisville themselves. While they spoke highly of living here, they said they had to travel to Nashville to find the closest temple.

By now, Pasupuleti’s shortest move had been from Lubbock to New York, around 1,795 miles between. The 120 miles from Louisville to Bowling Green pales in comparison, but he found little trace of his own culture when he first arrived.

He found the opportunity was worth the lack of familiarity, and soon Pasupuleti opened the Center for Pain Management, partnered within Cumberland Brain and Spine, in 2009.

Over time, his work brought him closer to Nashville, and he found himself once again fighting long commutes in metro traffic. When his partners asked him if he’d move to Nashville with them, he declined.

In 2013, Pasupuleti moved his practice into an office just off 31W Bypass, where it remains to this day.

“I’ve established myself as one of the leading pain practitioners in around 50 miles,” Pasupuleti said. “Everybody knows, even in Louisville, that this is a good practice.”

“When I came in here, I wanted to know what the needs of the Indian community were,” Pasupuleti said. “Within about one month, I organized a meeting for all the Indian families I came to know, which were just a handful of families, maybe 15 families or so.”

He’d hoped to connect a burgeoning community and, in the process, learn what the community needed to thrive.

“The loud and clear [message] that I heard was that they needed their children to have some connection to their heritage,” Pasupuleti said.

The years spent in Bowling Green without a nearby temple didn’t bother him too much — most Hindu households have their own “temple” in the way of shrines. What did bother him was the lack of cultural variety his daughter, then 8, experienced.

In India, Pasupuleti was surrounded by a plethora of faiths and often attended other places of worship outside Hinduism. When he was young, he’d even attend Christmas services with friends — though, he admits the good food had a major role.

He wanted the same experiences for his daughter, but found them difficult to find. He wanted to change that.

His daughter had learned Indian dance and ballet in Louisville, so Pasupuleti took her to lessons in Nashville once they moved.

“We went to Nashville every Sunday for 15 years, and that was for about six hours because my daughter would learn [Indian] dance and music,” Pasupuleti said.

Each time, the pair would make a stop at the Sri Ganesha Temple in Nashville.

“I wanted to at least give the opportunity for her to know what roots she has and where she comes from and what knowledge systems she comes from,” Pasupuleti said. “Even the dance that she practices is over 3000 years old, and so you have such a rich heritage.”

Still, it was difficult to manage the travel, and many families around him lacked the same opportunity. This led him and his wife to establish their non-profit organization, the India Culture and Heritage Group, in 2009.

They began teaching classes on Indian culture and language at WKU’s ALIVE Center every Saturday for classes of around 30 students. In addition, Pasupuleti began conducting classes for WKU students from India to help them integrate into the U.S.

“I realized that it’s a culture shock for anybody who comes here, so my whole idea was to lessen the impact of that culture shock,” Pasupuleti said. “They loved it, because they were completely, totally lost. They were by themselves, very young guys and young girls, and I could see it in their faces.”

Driving lessons, Bible study, career advice — there were few topics Pasupuleti wasn’t willing to help his students with. Many were on similar career paths as Pasupuleti, so he’d let them observe at his practice and write recommendation letters when they applied for residencies.

Despite the work the Pasupuletis put in across the community, they still lacked a local haven for their faith. As early as 2010, Pasupuleti spoke with others about potentially building a temple but quickly found the funding wasn’t there.

“We talked about it and talked about it for about a year, two years, three years, four years — the discussions went on, but they didn’t go anywhere, so the idea was dropped,” Pasupuleti said.

Pasupuleti had more than enough to focus on — his daughter’s high school graduation, his new practice, and his non-profit. Meanwhile, in the following years, more and more Indians came to the city.

“In this time period between 2010 and 2015, there was a huge influx of business from India, from the ‘Gujarati’ community,” Pasupuleti said. “By definition, they are the business community, with roots dating back to India.”

To call them entrepreneurs, Pasupuleti said, would be underselling their skills. Pasupuleti said hundreds of families flocked to the city, carrying with them new businesses and a renewed desire for a local temple.

Things began to change when Nick Patel, a local businessman, approached Pasupuleti with plans to finance a temple. Things were finally moving, but it wouldn’t get any simpler.

“The problem with constructing a temple is that there are so many denominations,” Pasupuleti said. “There’s so many different belief systems in India that you can’t have all of them together, because each one is demanding their own representation.”

The new arrivals came from every corner of India, many speaking completely different languages. Hinduism is no monolith — each family came with their own way of worship and life, some vastly different from others.

The temple’s funding came in part from the International Swaminarayan Satsang Organization, which aids local temples with charitable contributions. Pasupuleti noted to his colleagues, however, that there were many outside the Swaminarayan tradition that would want to visit the temple.

Venkateshvara, for example, is one god not traditionally found in Swaminarayan temples. Typically worshiped within southern Indian denominations, Pasupuleti was able to convince Patel to add him to the temple.

“Your denomination is great, wonderful, love it — but a lot of other people want to get into the temple,” Pasupuleti recalled telling Patel.

For Pasupuleti, this is the point of Hinduism — to bring everyone under one umbrella.

“[Hinduism] has always existed, since the day that the first human being was cast into this world, because whatever experience you have, that is Hinduism,” Pasupuleti said. “Whatever experience you have, that is what the Vedas say. Whenever you see something, you feel something, that is Hinduism, that is a part of human life.”

Pasupuleti notes that the word “Hinduism” is not used in India, but more commonly “Sanātana Dharma” — or “Eternal Dharma.” It broadly consists of hundreds of denominations from across the subcontinent, with loose, oral traditions that bind them together.

The term “Hinduism” itself stems from the Persian word for any people beyond the Sindhu River, and . When European colonists began exploiting the subcontinent, they adopted the word.

Pasupuleti says inclusivity is the very point of his faith, and must be when it is as diverse as his. Even if you’re a Christian, a Muslim or an atheist, Pasupuleti says, you can still be a Hindu, and you’re still welcome at the temple without the pressure of conversion.

In 2017, as debates about best practice came to a close, and with funding secured, Patel located a spot he thought was suitable: a lot containing three vacant buildings, formerly utilized by a furniture business.

When a Swaminarayan temple in Louisville was vandalized with Christian messages in 2019, Pasupuleti wanted the lesson to be clear: they had to bridge the gap between their community and others.

Pasupuleti said in order to avoid similar persecution, the temple community needed to branch out. Pasupuleti focused on forming connections with local religious leaders of varying faiths, inviting many to join them when the church was completed.

Over the coming years, Patel and the community would convert the buildings into the sprawling temple seen today.

Construction finished in 2021, but the pendulous nature of COVID-19 at the time made Pasupuleti nervous. Patel had been preparing for nearly a year, and canceling the event would be costly and frustrating.

“As a physician, as someone who’s in charge of other people’s health in this community, I would not let Bowling Green go through that,” Pasupuleti said. “This is my community! I have to protect it, so I would not allow that to happen.”

Despite the loss of time and money, Patel was understanding and postponed the event for a later date.

Finally, in May 2022, the temple opened its doors to the public. Community leaders such as Mayor Todd Alcott and then-State Representative Patti Minter joined in the celebration, and a procession of gods marched from Greenwood High School to the temple.

A year later, the temple hosts numerous Hindu celebrations, often several a month, and every Saturday bakes a sprawling Indian dinner for attendees. Event space is available for rent for any private function, Hindu or not.

There are no requirements for entry, nor expectations of belief — everyone is welcome in the temple.

Pasupuleti said people come primarily for two reasons: to connect with their culture and to connect with their god.

“It’s a very personal relationship, and everybody who comes to the temple comes with a personal agenda,” Pasupuleti said. “Nobody knows that agenda except for that person and god.”

Locals attend daily, but occasionally, out-of-towners find their way to the temple in search of something — their own agenda, perhaps.

Pasupuleti recalled a man who recently who was traveling the country, seeking “answers about life.” They met at the temple and discussed the financial and familial troubles that had brought him there — lost jobs, lawsuits, a crisis of spirit.

With respectful honesty, Pasupuleti told him that the answers would not come from traveling, nor from spiritual awakenings.

“People from the West have all gone all the way to India to find some peace, asking ‘how do I find solace? Where’s god?’” Pasupuleti said. “I told him ‘Look inside yourself, not outside. If you’re looking for god outside, you will never get god.’”

Pasupuleti talks often of the power of perspective, of our need to look beyond our own and into others’. The temple, he says, simply offers perspective — what others make of it is up to them.