1972 WKU alum Karen Stewart grew up in Beaver Dam, which she described as “about the most religious place you could ever land in your life.”

As a child, Stewart always felt more like a boy than a girl, had more traditionally masculine interests and hated traditionally feminine clothing. She realized her attraction to girls at 12 years old, which “terrified” her because of how both society and the generally Baptist population of Beaver Dam then viewed the queer community.

When Stewart first came to WKU in 1968, positive changes were occurring within the LGBTQ+ community such as the 1969 Stonewall riots and the first gay pride parade in 1970. However, it was still largely unaccepted for those in the community to be out.

“I had to formulate a plan,” Stewart said. “I was going to graduate from high school, go to Western, get a degree that

would qualify me to work some job somehow. And then after I had a job, I could be financially self-sufficient, and I could do

what I wanted … nobody could at least, starve me, or anything like that.”

Even though Stewart was not out to others about her sexuality on campus, she believes people knew her identity anyway.

One night during her freshman year, Stewart went to an off-campus party.

After a while of sitting by herself, she noticed a guy looking over at her and mumbling under his breath.

“What he said to me was, ‘sure would like to f– a dyke,’” Stewart said.

She left that party soon after and did not return to any more during her college years. This experience – one not uncommon to queer people during this time period – was extremely off-putting to her and caused her to never truly feel safe on campus.

“When somebody says something like that, it doesn’t do a whole lot for your sense of security and bodily integrity. That was my freshman year, so after that, I just kind of did what I needed to academically, and that was it,” Stewart said.

Stewart also felt some of the straight women on campus expressed “predatory” behavior towards her. She felt she was approached with the attitude that if the women treated her nicely, then they expected Stewart to do things for them.

“I felt taken advantage of a few times by a few people … I was just looking for friends so I wouldn’t be lonely,” she said.

She did, however, find joy in playing the bass clarinet in the WKU band, and had a close friend in the music program that was a gay man.

“I kind of had a person I could go to if I needed a male escort or something. He’s gay, so you know, we would sometimes just go [places] together,” Stewart said.

Stewart graduated in 1972 after studying sociology and folk studies. She worked as a caseworker before she graduated from the University of Louisville School of Law in 1986 and became a law clerk.

In 1992, she opened her own law practice that focused on working with LGBTQ+ clientele. She married her wife in Canada in 2004, and they now reside together in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

GEORGENA BRACKETT

When Georgena Brackett started WKU in 1983, she was still attempting to date men like her siblings and friends were doing.

During her sophomore year of college, however, she got into her first lesbian relationship.

“I realized that that was my comfort zone and that’s what I had been missing in my life as far as dating, having strong feelings for someone,” Brackett said.

Residing in Bowling Green, Brackett is now a director of health information management at Med Center Health. She also is a part-time faculty member in the Department of Social Work and president of the National Alumni Association Board of Directors at WKU.

In college, she continued to “fly under the radar” and stayed closeted, not attending any social events with her girlfriend.

The global AIDS crisis officially started in 1981, which caused both substantial deaths and increased hate towards the LGBTQ+ community from society. Brackett said if she had shown support for the community or been out herself, she thinks it would have impacted how she was treated or respected by her peers.

“I really didn’t have any negative interaction [while at WKU] at all. But I think because I was so closeted, it never presented as an opportunity to be treated any differently, ” Brackett said.

She said in hindsight, she is sure there were other queer people on or around campus while she was a student, but that she was completely unaware of any specific opportunities to engage with them socially or organizationally.

“I didn’t have knowledge of what to do, or how to do any of that, nor did I have the encouragement or the self-esteem to pursue anything outside of my class responsibilities,” Brackett said.

While on campus, she worked as a tour guide at the Kentucky Museum and was a resident assistant at Rodes Harlin Hall.

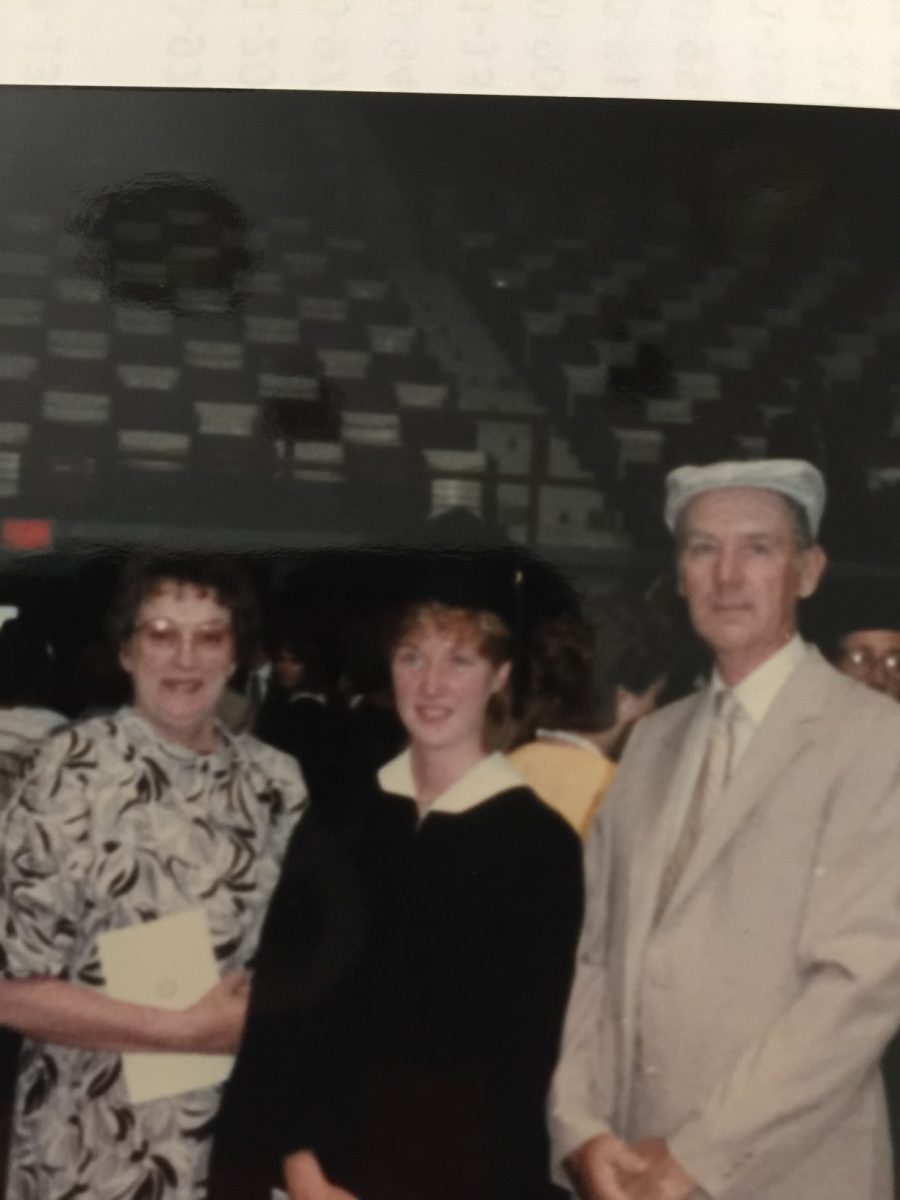

Brackett graduated from WKU in 1987 after obtaining her medical records degree. She then went back and obtained a bachelor’s degree in general studies with an area of concentration in psychology in 1992. In 2010, she graduated from WKU for a third time with a master’s degree in business administration.

In 1992, she met the “love of her life” at a work event. She and her wife had a union ceremony in 1997, where they invited family and friends and were “completely out at that point to anyone and everyone that was in [their] lives.”

Brackett said that her experience as a graduate student at WKU was completely different than when she was an undergraduate student. She said she would often make comments about her wife to others or invite her wife to social gatherings with her peers.

“It was a completely different, night and day experience. A kind of wonderful experience with my WKU connections at that point, having [my wife] on my side,” Brackett said.

SPENCER JENKINS

Growing up in the east end of Louisville, Spencer Jenkins always knew he was different.

“I think we all say that. We all knew we were different to some degree,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins graduated from WKU in 2012 after studying news-editorial journalism and criminology and working as a reporter for the College Heights Herald. He is currently the executive director of Queer Kentucky, a “diverse, LGBTQ+ run non-profit based in Louisville” which he founded, that brings awareness to the LGBTQ+ community.

He first questioned his sexuality around 10 years old and continued to do so throughout middle school. He felt that he comfortably came to terms with his queerness the summer before his junior year of high school, and came out to his family during the winter of 2007.

“My family was accepting for all of like, 18 hours. And then, I don’t really know what kind of reality set in with them, but I can kind of empathize to a degree … they had seen nothing but negative,” Jenkins said.

Societally, LGBTQ+ acceptance was progressing, but there was still a certain stigma surrounding queerness. This was prevalent for members of his parents’ generation since they had witnessed tragedies like the AIDS crisis and the murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay man who was brutally attacked in 1998.

“I was so sure of myself, too,” Jenkins said. “So, it was very disheartening and traumatizing to be so sure of something, and then have the people that are supposed to accept you, take care of you, love you no matter what, love you unconditionally just disregard and ignore and repress the authentic self I was coming into.”

When Jenkins started attending WKU in 2008, he became a member of the Kappa Sigma fraternity to feel “traditional” or “normal.” Surprisingly to him, there were a few other men who were involved in Greek life and also out as gay. Jenkins said the straight fraternity men were even very accepting of their queer fraternity brothers.

“It’s so weird that something so stereotypically homophobic and toxic kind of became the place that I found acceptance for the first time,” Jenkins said.

The queer community was making progress towards social acceptance as Jenkins continued to attend WKU. In 2008, across the nation, states were fighting for the right to same-sex marriage, and in 2009, the gay-oriented social networking and online dating app, Grindr, was released.

Throughout his time on campus, Jenkins kept searching for acceptance in his identity.

He said that he was unaware of WKU offering any services to aid students in the LGBTQ+ community, but remembers going to a campus therapist at one point.

Jenkins said he felt he often had to get “f– up” since he had not yet found a way to navigate his family and society in relation to his identity. He also was so unsure of himself that he did not feel he could fit in anywhere.

“I was doing anything I could to numb out who I was. Because who I was, was bringing nothing but trauma in my life,” Jenkins said.

Even though he was still dealing with obtaining complete acceptance, by the time he was 20 years old, Jenkins was fully out as a queer individual and had gained support from close friends he had made.

SETH CHURCH

Seth Church had what he described as “a pretty religious sort of upbringing in rural Kentucky on a farm.”

In regards to his sexuality, he had known something was “off” since he was young, but thought of it only as a test of his religious faith.

It was not until Church got to WKU in 2011 that he became internally comfortable with his identity as a queer man by making genuine friendships and meeting peers who were out, even though he was still closeted.

“I established a really close group of friends who I could talk through things with and get involved [with],” Church said.

Around the time Church attended WKU, the LGBTQ+ community was seeing advances of acceptance take place. In 2011, openly gay, lesbian and bisexual men and women were permitted to serve in the military, and in 2015, both same-sex marriage and adoption were legalized in Kentucky.

Church graduated from Western in 2015 with a political science major and a legal studies minor. He graduated from Emory University School of Law in 2015 and is now a litigator in Lexington. He is also on the board of directors and secretary for AVOL Kentucky, an organization “dedicated to the eradication of HIV and AIDS.”

Church was heavily involved with the Student Government Association during his time on campus. He said that one of the proudest things he did was writing a resolution to declare the SGA office as a designated safe space for queer people to come to if they needed support.

“I was so excited about it,” Church said. “I put up a little paper printed-out sign that I made saying, ‘This is a safe space,’ under the resolution number. And then, a few years later … I was sent a picture where [SGA] had bought a very nicely made plaque that went up in place of my little paper sign.”

Even while in the closet, Church also joined some queer-focused organizations on campus. He was on the board for the Campus Pride Index and helped plan the first annual WKU Lavender Graduation Ceremony during his senior year in 2015.

The ceremony is an opportunity for members of the LGBTQ+ community to be celebrated in their sexual identities as they graduate from Western.

When it was time for the Lavender Graduation to take place, Church was asked by his advisor if he would be attending the ceremony as an allied guest. He took her by surprise when he said he was going to be walking in the ceremony himself.

“That was my coming out,” Church said. “I didn’t come out until I was literally graduating college. I think I had probably figured it out fully, that I was queer. And I had told people, probably freshman year of college, but I really didn’t come out until I was graduating.”

In more recent years, queer support on campus has only increased. Student organizations such as the Queer Student Union and Out in Honors have provided the opportunity for LGBTQ+ students to be immersed in the community with their peers. The Pride Center, Hilltopper Pride Network, WKU Alumni Association Topper Pride Alumni Chapter and the Intercultural Student Engagement Center have been put into place institutionally for campus and its faculty to create an accepting environment at WKU.

These groups host social events for students to attend and also provide information, help and support for those who may be struggling in their identities.

“There is still room to grow and advance our community as an LGBTQ+ population on campus … I think Western is making advances in those areas, and I’m very proud of the work that’s being done,” Brackett said.

News Reporter Ali Costellow can be reached at ali.costellow453@topper.wku.edu