East vs. West(ern) Oral History Project — Part 1: WKU football welcomes Russian Czars to Bowling Green

April 17, 2020

Just 27 years ago, the WKU football program was on the brink of extinction. Long before the Hilltoppers became a consistent winner in the Football Bowl Subdivision or Conference USA, the university’s underperforming football team played as a Division I-AA independent.

The university needed to implement a state-mandated $6.1 million in budget cuts for the 1992-93 fiscal year, and Hilltopper football ended up on the chopping block in April 1992.

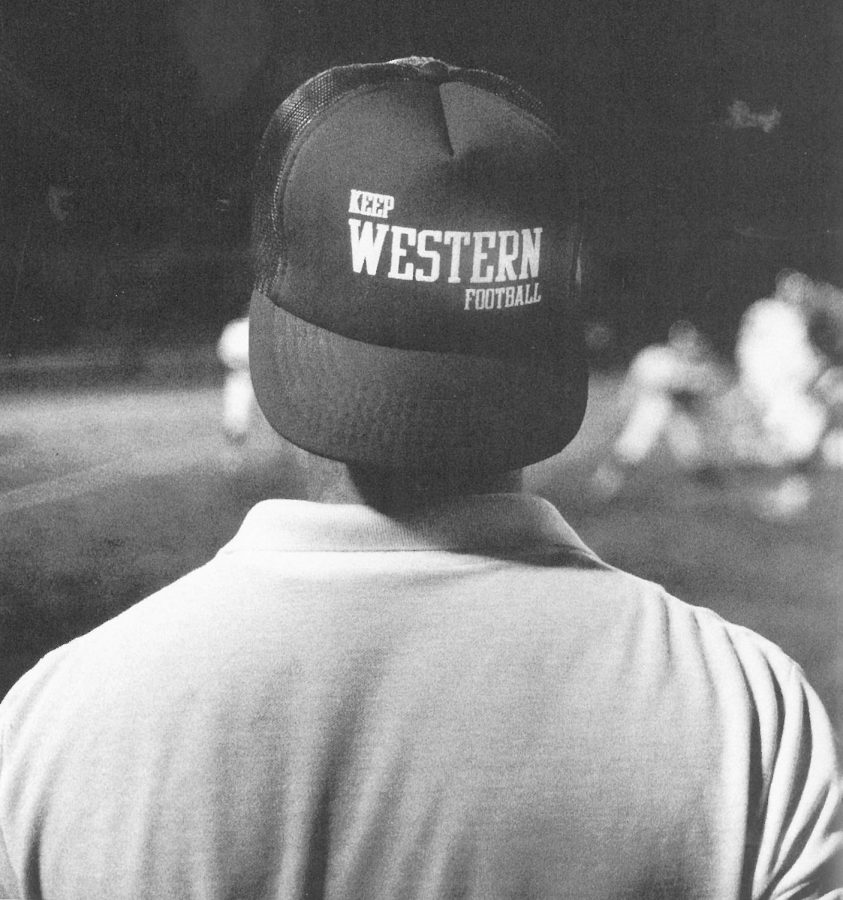

Tensions rose and tempers flared, but a combined last-ditch effort by a vocal collection of program supporters helped WKU football make its most crucial goal-line stand to date.

The Board of Regents approved $6.1 million in cuts on April 30, 1992, but the WKU football team was spared. Although the Hilltoppers dodged elimination, the WKU football program’s annual budget decreased to $450,000, which was about half of the previous year’s funding.

Head coach Jack Harbaugh was faced with several dilemmas — fewer scholarships and less full-time assistant coaches were to be expected, but schools dropping off his team’s 1992 schedule after rumors told them WKU would cut football wasn’t a foreseen consequence.

With the help of athletics director Lou Marciani, the 1992 WKU football team replenished its schedule. By the fall of 1992, the Hilltoppers were locked into a 10-game regular season schedule that featured two open dates very close to one another on Oct. 3 and Oct. 17.

Desperate to drum up any sum of money for the still-ailing football program, the Hilltoppers scheduled an exhibition contest against the Russian Czars — an American-style football outfit featuring alleged Olympians among several other standouts from different sports — on Oct. 17.

Although the contest ended up in the record books as the first time a Russian football team had ever played on a Division I college campus in the United States, the off-the-field antics that filled the week leading up to the showcase overshadowed everything that happened on the gridiron.

The Herald conducted 11 interviews over the course of the Spring 2020 semester, granting many of those who were involved in one of the most unique contests in college football history their first opportunity to recount the days leading up to the spectacle in their own words.

Quotations from archival news articles are also included in this oral history to help fill in the gaps and provide additional context to the thoughts and feelings of those closest to the exhibition.

Background information for this oral history project is presented in italicized type, while direct quotations are presented in normal type. Names are listed with the person’s job title during the 1992 football season.

(Note: Some responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Chapter I: ‘A piece of the puzzle’

The WKU football team posted a combined 5-16 record across the 1990 and 1991 seasons, making the program a prime target when the university needed to implement $6.1 million in state-mandated budget cuts in April 1992. Hilltopper football had been losing games and spending more money than it took in each year, which made the program vulnerable.

Jack Harbaugh (WKU football head coach): “It all started with the meeting with the president in his office in March of the spring previous to that [season], when he told us that he had the votes to drop football, but they weren’t going to vote until the end of April. He suggested that we not go through spring practice because of the risk of injury and those types of things, that there would be no football at Western the next year. Our players voted to go through spring practice.”

Rick Denstorff (WKU football offensive line coach), speaking to the Talisman in 1993: “It was a blessing in disguise. It helped get rid of players who were just going through the motions and opened up opportunities for more team·oriented players.”

Lou Marciani (WKU athletics director): “I don’t remember the exact date, but [then-WKU president Thomas Meredith] called me up to his office and said, ‘Lou, I have bad news for you.’ And I said, ‘What’s the matter, Dr. Meredith?’ He says, ‘The Faculty Senate voted to eliminate football. We’ve got a problem.’ I was stunned. So, at that point I said, ‘Well, can you just give me some time to think this through and what we can do?’ I did not think we didn’t want football on Saturday afternoon or Saturday evening in Bowling Green.”

Joseph Iracane (Former WKU Board of Regents chairman): “During my tenure at Western, there were a lot of financial difficulties and, I can attest to that fact, wanting to try to solve the financial problem by dissolving an athletic program. The budget was always a big to-do. I had a very elementary understanding of the budget and the fact that this is all of the money you have. You can’t make money out of nothing. This is it, so now you’ve got to spend it as wisely as you possibly can. Probably the thing we spent the most time on with the president was developing a budget that was necessary for the interests of the whole university and not a special interest group. We had some interesting debates, some of which were good. Some of them weren’t.”

Arvin Vos (Faculty Senate chairman), speaking to the Talisman in 1992: “I understand no one likes to lose a program. For many years, the football program has been costing the university far more than it brings in. That money should have been used for class.”

Marciani: “It was just a rough time in Frankfort at the time. The funding was cut, and it was a rough time for Kentucky in ‘91, ‘92. We were part of that ‘where do you cut?’ kind of concept, and football was selected.”

Vos, speaking to the Talisman in 1992: “The goal of the Senate was to get the budget in line. We decided we can’t afford the millions, so it would be better to suspend the team.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “The thing about finances really wasn’t the driving thing in it. The driving thing in it was Dr. Meredith had been getting some pressure from the Faculty Senate. That was his carrot. He was going to throw football out of here to try to put himself in good position with the Faculty Senate.”

Marciani: “I could have very easily said to Dr. Meredith, ‘I hear you.’ Because basketball at that time, we were riding real high in the ‘90s, meaning to the point where we were — we’ve always been a basketball school, but we were at a high level at that point. We were kicking butt for a little bit there, and so the basketball people probably didn’t want football. I’m just talking, but they thought the money that we used for football could be going to basketball probably. And that’s not true. So, we had that basketball versus football mentality on campus at that point in time and people thought maybe we’re wasting our time with football.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “That was one of the reasons, too. Drop football when football is not doing well and no one will really care.”

Lee Murray (WKU football running backs coach), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “When I was here in the ‘70s, everyone rooted for everyone else. I’d like to see that again.”

Iracane: “I felt like athletics is an educational classroom. Soccer is not just kicking the ball and running up down the field. It’s a learning experience. You learn how to develop a relationship with people, discipline and how to be on time. There’s just so many things that the programs bring to a young person. I felt like doing away with an athletic program is like doing away with a classroom program that’s — in my mind — very necessary for the success of a young person moving forward into business, industry or whatever they happened to do. To me it wasn’t even a close encounter. I just felt like, ‘How could you do this?’ It’s just not the right thing to do.”

Estill “Eck” Branham (Self-proclaimed “No. 1 fan” of WKU football team), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “I can’t see how in the world they can justify dropping football at Western. It’s part of college to me.”

Marciani: “The first phone call I ever got — because it hit the newspapers, I think — was from Howard Schnellenberger, the football coach at Louisville. He called and said, ‘What’s going on in Bowling Green?’ I said, ‘Coach, we might have to drop football.’”

Harbaugh: “We got support in our community. Jimmy Feix, Butch Gilbert, Mickey Riggs — I call them the three amigos — they rallied support among the former players.”

Marciani: “There’s a lot of people that wanted to save it, and I was right there in the middle of it, obviously, because I believed in saving it. It wasn’t just Lou though. Coach Harbaugh killed himself as well. [Coach Feix], he was heavily involved. The whole booster club. It was an effort by a lot of people that were really Hilltoppers for football. They really, really believed in the history of the game being played at WKU and our tradition.”

Jeff Nations (1993 Talisman sports editor): “Ever watch the opening scenes from ‘The Waterboy’? That was pretty much it. Just complete apathy bordering on hostility to budgeting that program.”

Jimmy Feix (Former WKU athletics director), speaking to the Herald in 2003: “That’s when we started writing and calling for solicitations. We tried to drum up ticket sales. All the politicking was great, but probably the single most critical element was Jack Harbaugh did not leave. He didn’t need this program and those headaches … he dug those heels in and did not leave.”

Harbaugh: “At the end of April, the vote was changed. One vote was changed and we got a chance to keep football, but we lost half of our operating budget, we lost 13 scholarships and we lost two coaches. The thing that we lost equal to that was teams saw the news for one month that we wouldn’t be playing football and canceled games. We were independent at the time, so we weren’t in a conference and we weren’t locked into games. Our athletic director had to go out and find those games. Well, we lost three or four of those games, and at one time we only had like seven, eight games on the schedule. So, we were looking for any possible opportunity to play football and to fill those games.”

Marciani: “They cut the budget on me. We scraped. There’s some games we bought in that ‘92 season. When I say buy, they gave us some guarantees to offset some of the cost. We had the ‘92 season to get on our feet and finance a program the president had been directed to take.”

Those closest to the WKU football program at the time have slightly different recollections of how the game against the Russian Czars came about, but all signs point to Marciani being the one who discovered that a traveling troupe was playing American football across the country.

Jim Clark (WKU coordinator of marketing and promotions): “There was excitement from people who had gone in to keep football, and we just needed to play as close to a full schedule as possible. I think the uncertainty over whether we would have a team made it difficult to schedule that year.”

Paul Just (WKU sports information director): “I don’t remember exactly what all they did to try to fill that date, but it seems like it was something to do with some change that created an opening that wasn’t supposed to be. Lou Marciani did a lot of the football scheduling for Coach Harbaugh and they were wanting to fill that spot so they could play another game because the limit had gone up to 11 games a year by that time.”

Bill “Doc E” Edwards (WKU head athletic trainer): “We didn’t have 11 games on the 1992 schedule, so that’s my understanding of why we did this exhibition game during the season. I think it was Lou’s idea. I think Lou found out about it and it was his idea to use that as a home game to bring in a little more revenue for the program at the time, which seemed kind of strange to everybody that Russia would have any kind of football team, much less play us.”

Just: “Somewhere along the line Lou stumbled across — I’d never heard of it before — a Russian national team in American football, which is not played over there regularly. There were some other teams that they played, I think in Europe and that sort of thing, and they had a little bit of a schedule. They were making a tour of the United States and played like coast to coast.”

Eldon Cunningham (Russian Czars football head coach): “I was searching the NCAA site and saw teams looking for games, so WKU didn’t have a full schedule of games. Contacted Coach Harbaugh, and we made it happen.”

Harbaugh: “We got the information that this team from Moscow was going to tour the United States and they were playing games and they were looking for games.”

Cunningham: “What I was looking for was more to get players experience and let them see what real teams looked like so that they could get a better grasp.”

Just: “What’s obvious since it’s ‘92 is we survived [budget cuts] with football, but we needed all the income we could get. Lou and Jack didn’t want two open dates — they wanted to generate some income. You almost never hear of an exhibition game in football, but they had a date when we had a date. They wanted to play, and [Marciani and Harbaugh] needed every bit of money we could get because we kept football, but we didn’t keep the football budget.”

Marciani: “The whole year was a blur. We struggled so hard and I worked so hard as an athletic director with several people to generate funds so that we could save football. We had to put in some licensing for seats in Diddle Arena, the different levels and the different tiers. It made it pretty painful, and that hurt — hurt in the sense that people were not used to doing that. But it was a base of funding that guaranteed the least the university saw coming forward to support the program at a minimal level as it existed. Even still, we had to scrape here and there.”

Harbaugh: “I don’t know the process or how it all worked out, but we contacted them and the circumstances were that they wanted a place to stay. They wanted housing for a week and they wanted food and that type of thing. A place to practice, use our facilities, which we did. Our athletics director agreed to do that.”

Marciani: “The Russian Czars were a piece of the puzzle to generate dollars and do everything we could to maintain and elevate something — as it has now — for the future of the university.”

Although Oct. 17 was listed as an open date on the schedule included in the 1992 WKU football media guide, the date was later modified to reflect a meeting with the Russians. Team personnel still remember their confusion upon finding out they’d be playing their country’s Cold War rival.

Robert Jackson (WKU football senior wing back): “I thought it was something fun to do but weird at the same time. I didn’t understand the purpose behind it, but I welcomed the challenge of playing against athletes who were semi-pro athletes. I was a 21-year-old kid myself, so I thought it would be a good test for my teammates and I. I felt like this game was being used to curve relations between America and Russia and to bring positive change to the negativity at the time between both countries. To my knowledge, I had never met any Russian people, so I was intrigued to see what they were like and see if they were good football players.”

Mark Quisenberry (WKU football student manager): “We had teams drop off the schedule, so it was just kind of a flash in the pan. ‘Hey, let’s see if this’ll work out.’ It wouldn’t count on our records. Actually, if you look, you can’t find stats or anything on it anywhere. We picked up the game just on a whim. ‘We’ll see what we can do.’ Basically, everybody was going to get to play.”

Harbaugh: “We stumbled into it, and that’s not what we wanted. We would have rather played a normal schedule and the way we had done it before. But my vision was that we could take this and make it a tremendous educational experience for our players. I didn’t know if that would ever happen or if any of our players would interact with them, but that was my hope.”

Cunningham, writing to Bowling Green citizens, WKU students and the university’s faculty and administrators in 1992: “In a time when both American and Russian people reside in peace, it is only fitting that our two teams engage in friendly battle on the playing field. For this I say thank you to all those who are responsible. Thank you for making the world a better place for all of us … this exchange of culture will indeed enrich all of our lives and the lives of all who take part in this great game of American football as it has mine. Just by being associated with the good people at Western Kentucky University and the people of your great city.”

Click the PDF below to scroll through the game’s souvenir program:

Chapter II: ‘We all spoke the language of football’

The Russian Czars limped into Bowling Green on Oct. 12, 1992, fresh off a 35-0 defeat at the hands of Team USA, a U.S. Football Federation squad of semi-pros and amateurs, in Chicago one day before. The Czars were 3-3 after playing all of their first six games on the road, picking up wins over the Belgian National Team, Sweden and Norway by a combined 131-6 margin.

The Czars played their U.S. tour opener on “a crisp October afternoon” just two days after the visitors arrived from Moscow, carrying with them paraphernalia they’d also haul to Kentucky.

Edwards: “Seems like they were here a lot longer than they were, but my recollection is they were here that week prior to the game. They got here maybe Sunday or something like that and we housed ‘em down in [Douglas Keen Hall]. It seemed like a long week in a lot of ways, but I guess that’s all it was.”

Harbaugh: “The week of the game they rolled into town and pulled up the bus at the dormitory, and the interesting thing about that experience as I look back at it, the Iron Curtain had come down in the late ’80s, and they came, really, with wares, if you might. They had cases of vodka that they were peddling. They had former uniforms that the army had just — when the Curtain came down, some of the army just dropped their uniforms in the street and they picked ’em up. ”

Edwards: “They had brought all kinds of Russian memorabilia. Russia still had that Soviet Union emblem, the hammer and sickle. The Soviet Union had been dissolved, but they had a lot of that stuff, and so they were bartering stuff like that and watches and they had a lot of those [Matryoshka dolls]. My understanding is they were trading that for jeans and maybe some tennis shoes and stuff like that. The main barter was vodka, I believe, from what I have been told.”

Just: “I think some of the local clothing stores did real good on their sales of blue jeans. Back then, blue jeans were pretty hard to find in the Eastern Bloc, so to speak. I think everywhere they went, there were guys out spending their money on blue jeans and vodka.”

Edwards: “The guys down at the dorm, that’s a whole ‘nother story, and all I got was just the stories about what was going on down at the dorm. I think every night down at Keen Hall, that was quite an adventure. I think there was a big enlightenment for our guys.”

Just: “I remember a couple of those [Russian players] couldn’t understand why they couldn’t bring their vodka in the room. I mean, vodka is to Russia what beer is to Germany. It’s just a staple. So, that was a little curious. I said, ‘How are we going to have this?’”

The university’s alcohol-loving visitors had a full schedule of events planned, according to a team itinerary published in the Oct. 13, 1992, edition of the Herald. Events for the Russians to participate in during their stay included: a campus tour, a tour of the Corvette Plant, a tour of Mammoth Cave National Park, an Alan Jackson concert in Diddle Arena, a shopping trip to Greenwood Mall, the 10K Classic Road Race and many provided team meals to consume.

Cunningham said events like “the joint team banquet” and other social outings allowed his group of guys to “interact with everybody” and have meaningful dealings with American culture.

Cunningham: “One of the highlights for the players was going to the Corvette Museum, especially since they found out that the Corvette was designed by the head of the Corvette program, [Zora Arkus-Duntov], who was a Russian. So, that gave ‘em a sense of pride.”

Herald sports writer Chris Irvine penned a commentary titled “Czars enjoying same pleasures as Americans” in the Oct. 15, 1992, edition of the Herald.

Irvine wrote about spending a day with two members of the Russian Czars, and his words painted a picture of the Russian players as stereotypical young men interested in “food, clothes, money, alcohol and girls. Mostly the girls.”

Oleg Sapega (Russian Czars football defensive tackle), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “American girls are very friendly and nice … Busch [Beer] is very good.”

Andrew Claffey (Russian Czars football inside linebacker), speaking to the Herald in 1992: “The difference between Russian and American women is their degree of friendliness. Russian women are shy and quiet, while Americans aren’t afraid to come up and introduce themselves and ask questions … [Russians] drink [vodka] like water.”

Quisenberry: “They liked to party and have a good time. The thing was, if you toasted to your family or whatever like that, they continued to toast in enjoyment until you ran out of people to talk about. They were very hospitable and very enjoyable, but they were also very respectful of our culture. And it was cool and interesting for me to sit back and be able to take in the culture from Russia. ‘Cause it was kind of in that transition, Cold War down, and Russia was in a transition period. It was interesting to be able to sit there and listen to ’em talk about — I don’t want to say for things that we took for granted — for being able to walk down the street and go get something to eat or drink or anything like that. It was a different world for them.”

Jackson: “We hung out with them and I thought they were pretty cool to hang with in the dorms and in practice. They asked a lot of questions. One of them even told me he’d never been around black football players before and asked me a lot of questions about my culture. I appreciated him showing an interest in who I was versus stereotyping me based on who he thought I was, which goes on in this country a lot.”

Dan McGrath (WKU football freshman strong safety): “They stayed in the dorms with us, so we spent lots of time that week hanging out with them. They wanted to trade Russian military hats and jackets for blue jeans and tennis shoes. We treated each other like teammates during that week and really enjoyed our time spent with them. Although we did not speak the language, we all spoke the language of football, so there was plenty of bonding through practices.”

Quisenberry: “They didn’t live in the rooms with our players, but there were a bunch of empty rooms around our players. All week long, our guys, when they weren’t in class, spent time with their players. [The Russians] were really soaking in what was being shown to them, and I’m very appreciative. It was interesting to spend some time with them. Just a bunch of great guys.”

Jackson: “I remember them drinking a lot of liquor the week they stayed with us. They wanted to trade items for blue jeans. I don’t think they had many blue jeans in their country. I thought that was hilarious. It’s an experience I will never forget.”

Along with the memories he’s been able to cherish for years since, Quisenberry was able to obtain a piece of headwear that’s stuck in the minds of everyone he encountered in the ‘90s, which was quite a few people since the then-22-year-old “would put in a good 60, 70 hours a week working with the football program” while he finished “undergrad on the feel-good plan.”

Quisenberry: “I actually — up until about three years ago — had an actual Russian babushka type of hat. It was a winter hat that a Russian soldier would wear in the wintertime. One of the players gave it to me, just as a friendly gesture for spending time with him. He said, ‘I want to give you something,’ and he gave me that.”

Harbaugh: “About Tuesday or Wednesday, [Quisenberry] came into the office and he was walking around with this hat like the one George Costanza wore on Seinfeld. He had the high, square fur hat that he had procured. He came in and I said, ‘Where in the hell did you get that?’ He said, ‘I bought it. They sold it to me.’ I said, ‘Get that thing off your head for crying out loud.’“

Edwards: “Mark Quisenberry wore that hat all the time for a couple of years.”

Quisenberry: “I can legitimately say that I was able to walk around in the wintertime with a long-sleeve shirt on and sweatpants ’cause that’s how hot that thing was. I didn’t need a jacket. It was very warm.”

The Russian Czars were coached by 41-year-old Eldon Cunningham, a former quarterback at McNeese State. After a stint coaching high school football in the United States, Cunningham defected to Russia, where he coached the Moscow Bears to the first-ever Super Bowl in that country before he helped establish the Russian Czars football program in January 1992.

Harbaugh: “On Monday, we went out to the practice field and we met the head coach, Eldon Cunningham. He was from Houston, Texas, and he spoke English. He and I communicated, we went out and watched practice. They were hitting dummies, doing different things. We had a nice conversation and they practiced and we practiced.”

Just: “[Cunningham] was a bit of a character. I don’t know how much of what he shared with [Jim Clark] and I [was true]. Jimmy and I were both around him quite a bit, in that week’s time that they came in the week earlier, and worked out every afternoon. He was a bird. I know he told us that his ex wife was the daughter of the former governor of Louisiana. I don’t know if that’s true or not, among some other things, but anyhow.”

Harbaugh: “They practiced in the morning, like 10 o’clock, ’cause they had no classes or anything. So, they would use the morning to practice. They used our fields. They used our dummies and our blocking sleds and all the equipment we had on our practice field. And then we practiced in the afternoon. 4:30, 4 o’clock, our normal practice time.”

Edwards: “Back in those days, we practiced across the railroad tracks, where our track facilities are now. So, that’s where they practiced earlier in the day, and then we practiced later at our normal time. I can remember going over there the first day. I had one of my assistants be there with ‘em while they were practicing in case they needed any help the rest of the week, but I went over there that first day and we put ‘em down at the visiting locker room, down at the other end of the stadium. We were going down there and one thing I remember is that their equipment — their shoulder pads and their helmets and all that — were really inexpensive ones.”

Quisenberry: “Their equipment was outdated, to say the least. It was kind of like they bought it back in the day on what would be [similar to] eBay or whatever. I doubt half of it was certified.”

Edwards: “I remember jokingly saying they looked like they had Little League shoulder pads and stuff to one of those guys. It was low end of the spectrum equipment. The shoulder pads, they were kind of small and probably not big enough for some of the big guys that they had.”

Quisenberry: “Of course, most of those guys, even when they practiced, didn’t have helmets on, I don’t think. ‘Cause most of ’em were rugby guys, so they didn’t believe in it. For them the biggest thing was just getting out and getting exercise and the camaraderie of their comrades.”

Edwards: “My recollection is there were wrestlers on [the Russian team]. I remember seeing a handful of ‘em with cauliflower ears. We had talked about it in my profession, in athletic training all those years, but we didn’t have wrestling at Western. So, I had never seen anybody, really, with it. It was in all our textbooks and we talked about and we had to learn about it, but several of those guys had it. That’s where they get their ears rubbed so much from wrestling and all of that, it bleeds in there and fills up part of the cartilage there, between the skin and the cartilage, it bulges out and looks really awful. I remember several of ‘em having that. Those guys were older, and I don’t know what their age would’ve really been, but they were older. They were speaking Russian and whatever language they were speaking, so that made it interesting.”

Quisenberry: “They would practice during the day while our guys were in class and then they would just come and just watch us practice ’cause they wanted to see how everything was going to play out as far as American football, as they called it. ‘Look at this real American football.’ It was really exciting.”

Just: “There were some Americans on the team, too. It was kind of like most international or pro basketball overseas or whatever. You can have two or three or four non-native players.”

Edwards: “I remember they had a guy that they called their doctor that was with ‘em, and I don’t know if he was a doctor or more like an athletic trainer like myself, but I think he was a doctor. I know that the center for their team, the guy that was from the United States, was talking about how they injected some of their injuries and he wouldn’t let ‘em do it to him because he wasn’t sure if they were using another needle or not and crazy stuff like that. They had a little training kit, and it didn’t have much in it the way I remember it, training kit-wise. I remember us giving [the Czars’ team doctor] a pair of scissors, anyway. We donated a pair of scissors to the cause, but everything was pretty primitive with what they were doing.”

Quisenberry: “Their equipment, I would care to venture, would come nowhere near passing safety. As Doc E. said, it was very suspect, to say the least.”

Harbaugh and many others close to the WKU football team recalled the Russian Czars having an Olympic sprinter on their roster. The roster listed in the game’s souvenir program included a special note beside the entry for No. 24, Vladua Pouzerieav, a 6-foot, 205-pound running back.

The note for Vladua Pouzerieav read, “silver medal, 100 meters, 1988 Olympics.” According to Olympic.org archives, medals for the men’s 100 meters at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, went to Carl Lewis (gold), Linford Christie (silver) and Calvin Smith (bronze).

Several other players listed on the numerical roster for the Russian Czars had special notes beside their entries, but Google searches for their names and/or their accomplishments either resulted in a “did not match any documents” message from the search engine or confirmed people by the names listed had never received any awards, honors or Olympic medals.

Harbaugh: “In watching practice a couple times during the week, these guys were about as impressive a looking team as you’d want to see. I think they had Russian Olympic wrestlers. The middle guard was a big, big man. The running back, I think he finished second in 200 meters in the Olympics — just an outstanding athlete. But they had not played football.”

Cunningham: “The [Russian] minister of sports said that we could go to any venue and pick out any athlete and he would play football. We used wrestlers for linemen, both offensive and defensive. Track and field stars for receivers. My quarterback was a javelin thrower.”

Harbaugh: “I remember going over there, watching practice and marveling at what outstanding athletes they were. Figured we had no chance to win whatsoever. Just no possible way we can beat this team — as coaches do. We go back and tell our players, ‘I’ve watched it. We have no chance. I don’t know why we put this game on the schedule, we have no chance to win.’”

Cunningham: “For me, it was deciding on a roster that I could take with enough players. With the [Moscow] Bears, we had come over to play a game in northern New York and we had 21 players defect to Canada. So, my problem getting another team out to play in the States was political officers out there to make sure that players didn’t defect.”

Harbaugh: “You apologize [to the players]. ‘I apologize to you guys for putting this on the schedule. I had nothing to do with it. It was Dr. Marciani. He put this game down. I don’t know why he did it. We have no chance. Just play as hard as we can and don’t disappoint our fans.’”

Cunningham, speaking to the Associated Press in 1992: “We have NFL size, but not the experience. Nobody understands what they are supposed to be doing, but hey, we’re here to have fun. These players just need a chance.”

McGrath: “We were nervous, but we were excited about playing a team from Russia. Coach Harbaugh sold it to us as we were playing this great group of athletes — most of whom were former Olympic athletes — and he definitely had us nervous to be playing them.”

Much unlike the cash-strapped WKU football program, the Russian Czars were sponsored by Reebok, Pepsi and Miller Brewing Company. During their time in Bowling Green, the tourism commission also recruited local restaurants to feed members of the Russian Czars roster.

Although players weren’t being forced to pay out-of-pocket expenses, the Russians were still becoming unhappy about the quality of food they were being provided. “The entire team is getting sick of the fast food they are being given,” Irvine wrote for the Herald on Oct. 15.

Harbaugh: “On Wednesday, there was a mutiny. The [Russians], they felt they were eating too many McDonald’s and too many Burger Kings and they weren’t eating better food. So, they boycotted. They weren’t going to play. They were going to strike and not play the game.”

Edwards: “We got places to donate food, and I think [the Russians] got some meals out of it. I think they ate a lot of McDonald’s, as Coach Harbaugh tells the story. But the word was they weren’t going to practice. They were getting tired of McDonald’s, probably.”

Claffey, speaking to the Herald in 1992: “We had Burger King for breakfast, Wendy’s for lunch. What’s next, Taco Bell?”

According to the souvenir program for WKU’s exhibition contest against the Russians, the Czars were owned by Harry Rosen. Rosen — 68 years old, as of Sept. 5, 1993 — was a businessman from Las Vegas who took an interest in building relationships within the Russian culture.

The entrepreneur started his football team because Russians love sports and he thought it would be “a great promotional vehicle,” Rosen told News & Record in September 1993.

Harbaugh: “The owner was called in on Wednesday to try to talk ’em into playing the game, and I don’t know how he sweetened the pot to get ‘em to play, but they met on a Wednesday night in one of the classrooms there in the stadium and they decided to play.”

Edwards: “I think [the Russians] got paid to play. I don’t know how much. Probably not a lot, but my story is the owner flew up and either paid ‘em or talked ‘em out of it or something so that they got it worked out where they could go ahead and have that game.”

Harbaugh recalled an example of how concerned most players on the Russian Czars roster were with getting proper compensation for their services — even if that meant giving his daughter Joani the cold shoulder when it came to a potential educational opportunity.

Harbaugh: “My daughter, Joani, she was teaching at one of the northern schools there, an elementary school. She was teaching fourth grade or fifth grade or something like that. She said, ‘Dad, if a couple of those players would come out and kind of talk about Russia and the customs and life in Russia, that might be a tremendous learning experience.’ So, I think it was about Tuesday night or Wednesday, I went to the team — well, I might have gone to Eldon [Cunningham] — but I told them my daughter’s a school teacher and do you think a couple of your players would be willing to come out? And again, this is where my memory fades me. I can’t remember whether he told me or one of the Russian players told me: ‘They go nowhere unless there’s cash.’ So, I did talk a couple of the American players on their team into coming out and they did a fantastic job. I went out with them and the kids were really good and they were really good talking about their experiences in Russia and about the country. So, Joani did get an educational experience, but she didn’t get it from one of the [Russian] players.”

The upcoming exhibition game was already being billed as the International Football Classic, so Harbaugh decided he would partner with Cunningham to take the event to another level.

Harbaugh: “I had this brilliant idea — I mean, brilliant idea. Talked to the staff, I said, ‘You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to have an international practice. We’re going to bring our team out on the field there at Feix Field and we’re going to have our coaches working with their players. Our defensive back coach works with our defensive backs and their defensive backs. We’ll run through drills. They’ll watch, they’ll see football.’ Each and every position coach would do that, and Eldon agreed to do it.”

Edwards: “Coach Harbaugh embellishes the story to no end, but he was saying that this was going to be the United States and Russia coming together on a football practice field, soothing all their wounds about the Cold War and all that. Solving the Cold War here at practice in Bowling Green, Kentucky.”

Harbaugh, speaking to the Herald in 2003: “It was a dog and pony show to try to save football at Western Kentucky. I’m part of this dog and pony show. My entire life is football. I’m here with bells and whistles trying to support it by bringing in all this gimmick stuff.”

COMING SATURDAY: Chapters III-V, which include an arrest at Smith Stadium, a high-scoring exhibition contest for the Hilltoppers and reflection on one of the most unique weeks in the storied history of the WKU football program

Sports Editor Drake Kizer can be reached at [email protected]. Follow Drake on Twitter at @drakekizer_.

Projects Editor Matt Stahl can be reached at [email protected]. Follow Matt on Twitter at @mattstahl97.

Elliott Wells contributed reporting to this project.