‘Words are powerful’: Racial slur incidents spark on-campus discussion

October 29, 2019

Editor’s note: In previous editions of the Herald, we have refrained from using the phrase “N-word” and instead chosen to use “racial slur” in accordance with Associated Press style. This story includes direct quotes which use the phrase “N-word.” Direct use of the slur in quotes has been changed to read “[N-word].”

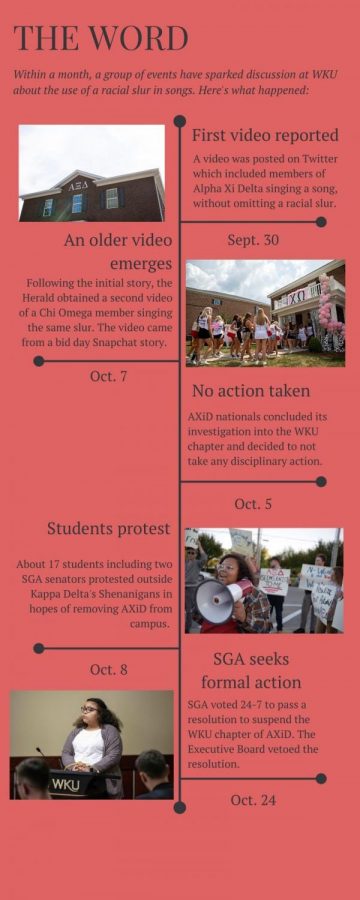

A Student Government Association resolution which called for the suspension of Alpha Xi Delta from Greek Affairs passed in a 24-7 vote on Tuesday. It was then vetoed by the SGA executive board, citing issues with a line item clause and noting that if passed, the resolution would set a precedent for SGA to withhold funding from student organizations.

The Faculty Senate will not see the resolution until it is brought back to the SGA senate for a revote in Tuesday’s meeting.

The resolution comes after AXiD faced criticism for a Twitter video posted in August which showed some of its members singing along to the song “My Type” by Saweetie, which included a racial slur, without omitting it.

The university did not pursue any disciplinary action after it was made aware of the video. Instead, it handed disciplinary responsibility to the organization’s national chapter and used the incident as a “teachable moment,” said Bob Skipper, director of media relations.

In an Oct. 5 statement to the Herald, the national AXiD chapter said it had concluded its investigation into the incident and would not pursue disciplinary action against the WKU chapter.

“[W]e have made it very clear to all of our members, whether that is through disciplinary procedures and/or continued education, that this type of behavior is not part of our organization’s values and principles,” the statement read.

Following the publication of the AXiD story, the Herald obtained a second video which was screen-recorded from Chi Omega’s Bid Day Snapchat story on Aug. 20.

The video included a sorority member singing along to the song “Act Up” by City Girls, which included a racial slur, without omitting it. Similarly, WKU left disciplinary decisions to the national chapter.

Skipper said Chi O members went through training on how “certain things can be perceived and misunderstood and for people to be more thoughtful about things they might post on social media.” The training was primarily focused on sensitivity and social media postings, he said.

Despite WKU’s decision to not punish either sorority, two SGA senators, Symone Whalin and Anthony Survance — who authored the resolution — held a protest to demand the removal of AXiD at Kappa Delta’s annual philanthropy event Shenanigans on Oct. 8.

The issue of non-black people using this racial slur in the context of a song isn’t unique to WKU.

“Jane the Virgin” actress Gina Rodriguez was met with criticism after she posted a video to her Instagram story where she sang along to “Ready or Not” by The Fugees. The portion of the song which she sang included the slur, according to a TIME report.

The video was deleted. Rodriguez then posted a video apologizing, saying she didn’t mean to offend anyone and adding that she’s a Fugees fan, according to the report.

Rodriguez, faced with criticism, then released a second apology as an Instagram post.

“In song or in real life, the words that I spoke, should not have been spoken,” Rodriguez wrote. “I grew up loving the Fugees and Lauryn Hill. I thoughtlessly sang along to the lyrics of a favorite song, and even worse, I posted it.”

The Herald’s coverage of both WKU instances started conversation on the slur’s usage in songs as opposed to its use in other contexts.

The amount of questions about the coverage prompted Editor-In-Chief Jeremy Chisenhall to write a letter to readers addressing the concerns.

The letter noted the social acceptability of the word and how it has changed over the years and how in today’s climate, it is generally viewed as unacceptable for white people to say it, regardless of whether in a direct reference or being sung in a song.

“When it comes to issues like this, we have an opportunity to highlight the importance of the issue and drive further discussion,” Chisenhall wrote.

History of the word

The word is derived from the Latin word “niger,” meaning black, according to Selena Sanderfer Doss, an associate professor of history and African American studies. The word for “black” in languages with Latin roots is similar, including the Spanish word “negro” and the French word “negre.”

The slur derived from a phonetic spelling of the mispronounciation of the word “negro” by white southerners, according to Doss.

The word was established as a “denigrative epithet” in the early 1800s with the rise of stereotypical caricatures like Jim Crow and others portrayed in black minstrel shows — performances where white people performed as black people in makeup or blackface.

“The word [N-word] came to be associated with a lack of morality, intellect and a lack of … social grace with it,” Doss said. “… You see more stereotypical and negative associations with the word, not just [as] a slang, colloquial term but a term associating with those negative characteristics and qualities too.”

After the Civil War, the word continued to be used as a “reminder of black inferiority to continue white supremacy — a cultural reminder,” Doss said.

The word in music

The administration handled the AXiD and Chi O incidents the way it did because their actions were “ill advised” but not malicious, Skipper told the Herald in an Oct. 24 meeting.

Skipper said the administration saw a difference between singing the word in a song as opposed to yelling the slur at someone directly.

If funding was denied to AXiD — as called for in the SGA resolution — based on the incident, Skipper asked “Where do you draw the line?”

“If a predominantly African American sorority is playing that music out on the South Lawn and that word comes over it, do we deny funding to them for doing it?” Skipper said. “…You have to look at what’s behind the action and not just the action itself.”

Saundra Ardrey, an assistant professor of political science and program director of African American studies, said words have an impact, especially in song.

“Words are powerful,” she said. “Words in music are even more powerful.”

Ardrey said the Kentucky state song, “My Old Kentucky Home,” used to include similar slurs and has changed often to become more acceptable, showing the power of words in songs.

“Because it makes us comfortable,” Ardrey said. “It’s with a melody, and it may undercut the real meaning of those words.”

The idea of using the word nonchalantly in song creates fear that the use reflects an underlying belief, Ardrey said. She called it “othering” people, which she defined as a belief that “You’re not like me, you’re other,” she said.

“And even if it’s not ‘versus’ or it’s not hateful, it’s just that you have ‘othered’ them, that they are not like us.

“Do they feel comfortable singing these songs because they are in a racially homogenous atmosphere? Are there no black sisters in that sorority, so they don’t know what their hurt is because they’re being ‘othered?’”Ardrey asked.

In Doss’ view, the act of singing along to a song doesn’t show inherent racism but instead a lack of sensitivity to black people’s feelings.

“You can sing along to a song that says the N-word and not be racist,” Doss said. “I think the larger point may be the lack of empathy and sensitivity to how black people could feel when you use it shows a racial prejudice.”

The word itself creates what Eric Deggans refers to as a “climate of oppression.”

Deggans, a TV critic for NPR and author of “Race-Baiter: How the Media Wields Dangerous Words to Divide a Nation,” said the word creates that culture when it’s used in a situation where a black person can’t speak up about how the word makes them feel.

Creating the “climate of oppression” is why the word exists in the first place, Deggans said.

“I think it is hard for white people to understand how using that word, even when you’re reciting the lyric to the song, or even when you’re quoting someone else, could help create a climate of oppression for people of color,” Deggans said.

“…That, to me, is why you try to be careful about how those words are used, and you try to discourage people from using them.”

Kate Horigan, an assistant professor of folk studies, said folklorists look at performances — like the act of singing a song — within contexts. Sometimes when a song is sung in one context but then moves to another, the meaning changes, she said.

“I think people who are making the argument that ‘Well, this word can be said in this situation but not this situation,’ or ‘We’re just singing along to a song,’ are not taking into account a new context gives that a new meaning,” Horigan said.

She used the song “Happy Birthday” as an example.

“It has a very different meaning if you’re singing it at your nephew’s third birthday party versus Marilyn Monroe’s performance of it,” Horigan said. “That’s the same words. It’s technically the same song, but when it’s performed in a new situation, by new people, for a new audience, then the meaning changes.”

The same rule of context can be applied to traditions, Horigan said.

“That word has a tradition, a history of being used in racist contexts, and so that all influences its performance in this context,” Horigan said.

The hip-hop genre has its own performances and contexts. Though the word carries a history of racism, it is also used often in hip-hop, a genre with roots in the black and Hispanic communities, Horigan said.

“When it moves out of that historical moment and out of that historical context, then you run the risk, not just of performing it in a way that can be perceived as racist, but also that can be perceived as cultural appropriation because you’re taking something that originated in another group’s culture and using it for a different meaning, for your own purposes,” Horigan said.

The context of music is key for any situation, said Quintez Brown, a University of Louisville sophomore and activist for youth anti-racism. He regularly writes about the young, black experience as a columnist for The Louisville Courier Journal.

“Context really matters, and I think for a white person — I think they need to realize the context of their whiteness and saying that word,” Brown said.

Brown said people wouldn’t sing or rap about things like rape or gun violence if they were surrounded by people who had been impacted by those things out of respect.

The respect comes from an understanding that the use of the word could be harmful to people affected by its past, Brown said.

“Blackface used to be just a joke — just a thing comedians would use to attract an audience and to make money, but when people started to realize that it’s harmful, it has roots back in racist violence, you don’t see people in blackface anymore,” Brown said. “I think the same thing applies to the N-word. [When] more people recognize the harm, the historical impact, historical legacy, it’ll stop becoming cool to joke about, or cool to entertain people with.”

Brown said since the rise of hip-hop in mainstream culture, black people have said they wouldn’t want white people to use the word given its historical context.

“When they use that word, there’s usually no accountability,” Brown said. “It’s usually just shrugged off as, you know, ‘It’s just a word, freedom of speech,’ and it’s always ignored the impact the word [has] on these communities where essentially it belongs to.”

What does it mean to reclaim a word?

Reclaiming a word gives it new meaning, Ardrey said. When the word is recaptured and turned into something to be proud of, the sting is taken away from it.

“We said it as a way of camaraderie, that ‘I see you,’” she said. “‘I see your suffering. We are still great.’”

Doss said young people have taken power from the word that’s been used against them for hundreds of years.

“African Americans are experts at reclaiming parts of their culture that have been derided and using that as a positive form of self-identity, and the N-word is a great example of that,” she said.

In notes from a presentation on the word, Doss called its contemporary use by African Americans “one of the most interesting and perplexing phenomena in American speech.”

Doss explained the colloquial use of the word could refer to all black people, black men, things, friends, foes or a term of endearment.

Contemporary use of the word is all about context, but usually when blacks use it with one another, it’s less offensive, she said.

Still, within the black community, the word is controversial, Ardrey said, which can be attributed to generational and class differences.

Some members of the black community who came of age during the civil rights movement, where the word was used frequently in a derogatory way, may refrain from using it because of the weight it carries, Ardrey said.

“But for young people that came through after that, the sting maybe is not as great, and so they see it as a way of capturing it — maybe of pride, of brotherly love, of solidarity within the community,” Ardrey said.

Another reason some are hesitant to use the word is because it confuses people outside of the black community who see their black friends using it freely among themselves, and they may think they can use it too, Ardrey said.

“When a white person says [it], who’s not a part of our community, it has a different connotation, and it brings up all of the connotations and negativity of the past,” she said. “Because you’re not part of a community, you have not been a part of that prejudice, that discrimination, so you cannot — we think — use it in that way.”

What happens now

Whalin, one of the authors of the SGA resolution, said the measure wasn’t meant to present a solution to the problem but rather call attention to the ongoing issue.

“It’s gone past just the initial video,” Whalin said. “There’s now a rhetoric being spread on campus, because the girls themselves and everyone else associated with it are now having to defend their use of the word instead of being able to just own up to it, apologize.”

Moving forward, Skipper said he would like to see a discussion come forward and not a punishment.

Skipper said the issue was harder for him to understand as someone who’s not of the same generation as students.

“What I don’t have a good understanding of is how one group of people who celebrate the word in music and who have entertainers profiting from music using that word can become so upset when someone of a different color says that word while singing along to that music,” Skipper said. “Maybe that’s an insensitivity on the part of the person who’s singing along with the music, and if that’s so we need to address that. Maybe it’s a being over sensitive on the part of the other people. Again, maybe that’s something that could be addressed.”

Skipper pointed to a lack of understanding of the definition of the word and said its ambiguity made it difficult from an administrative standpoint. The administration was faced with questions of “How do we educate students and give them the opportunity to grow but remain sensitive to what others might be feeling?” Skipper said.

“Just so that we can find what each position is, and maybe help the other understand, and maybe we can come to some resolution on this where everybody learns something from it, and we’re able to move forward and put it behind us,” Skipper said. “That’s the ultimate goal.

“That’s part of what college is all about. You get to experience different perspectives, different cultures and learn from them and that’s what I’d like to happen.”

To Ardrey, the conversation starts by not punishing people but by educating them on being culturally competent and sensitive.

“The key, and especially since we’re here at an educational institution, [is] to expose students, not so they change their opinions, but at least they know there are other ideas out there, that there are oppressive systems that continue to oppress and discriminate against people and to be more sensitive to that,” Ardrey said.

Print Managing Editor Laurel Deppen can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @laurel_deppen.