EDITORIAL: The problem with unpaid internships

March 26, 2019

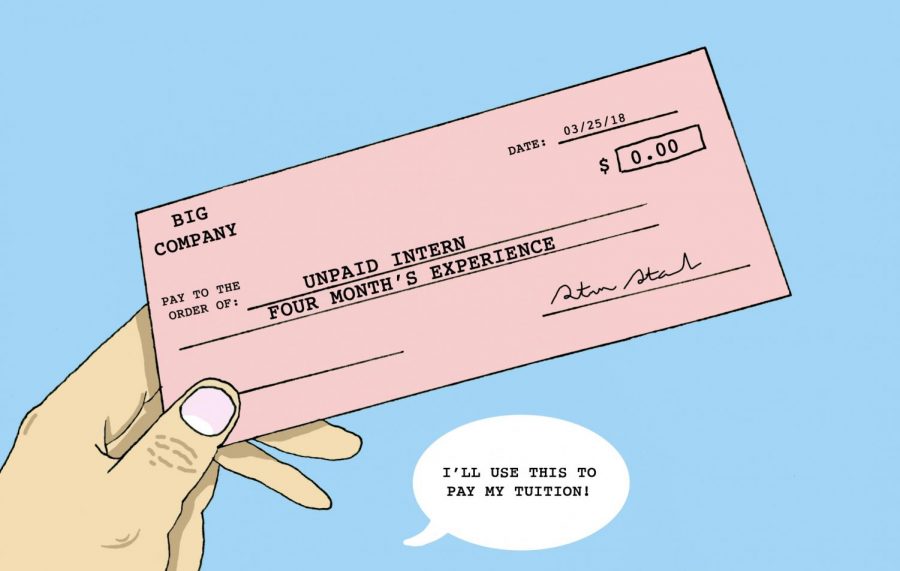

Issue: The majority of college students are expected to have completed an internship by their graduation, but many unpaid internships prevent students from being able to gain what is now often viewed as necessary experience.

Our Stance: An unpaid internship limits the demographic of people of who can apply for it due to someone’s financial standing and other factors that have nothing to do with their skillset, giving disadvantaged students even more obstacles to overcome.

Modern education puts such a high stress on internships that many colleges are making them part of their criteria for graduation.

However, almost half of the 1.5 million internships offered in the United States were unpaid as of 2014, according to Forbes.

Working for free is never ideal, and if someone is a first-generation college student or comes from a low-income background, their situation can go from impaired to impossible. This causes a fundamental detriment to students of color and students in the LGBTQ community since they often do not have access to the same resources as middle-and upper-class white students. Students without vital financial support can’t give away hundreds of hours of their time and be expected to supply themselves with their basic needs, especially if they are being asked to relocate. Some citizens in large cities like New York City or Los Angeles can barely afford to live there on minimum wage, yet employers expect young adults to survive in these conditions without receiving any income.

As if working for free wasn’t bad enough, most unpaid interns don’t have access to workers’ rights, as their lack of payment means they aren’t considered employees. In 2014, only New York City, Washington, D.C., and Oregon had given unpaid interns rights against sexual harassment, according to ProPublica.

A productive internship is more valuable than almost anything someone can learn in a classroom. Hands-on experience in a real-world setting is an asset that can’t be matched by any lecture or group project — that is, if the internship is actually working to better the intern.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed over the last decade from former interns who claimed they were used as glorified custodians or placed in other positions which involved little to nothing they applied to learn about, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education. The law states internships must benefit the intern, not those supplying the internship, according to the Fair Labor Standards Act, but this hasn’t stopped some companies from attempting to use interns as free labor for lowly work.

While comparisons of unpaid internships to slavery and indentured servitude are extreme and misleading, it’s accurate to say unpaid internships feed into a predatory system that enables an abuse of power.

In some regards, the situation is similar to the NCAA’s refusal to pay college athletes. Both groups of students are expected to work for free because they are told their current benefits are payment enough, and if they want to take the next step in their careers, then they should be grateful for the opportunity they have already. In reality, both groups are being exploited because they have no leverage, as the powers above them reap their rewards and save money.

Even if someone finishes an unpaid internship, their prospects still aren’t as bright as someone who has completed a paid internship. According to CNN Business, a 2016 study showed someone who has completed an unpaid internship will be offered a job only 44 percent of the time compared to paid interns at 72 percent. The same study showed former unpaid interns receive an initial salary offer $20,000 less than former paid interns.

The design of unpaid internships allows for veiled discrimination. The United States is supposed to be a meritocracy, but there is an inherent flaw in the system if those with adequate talent can’t showcase it because they don’t have the means to work for free.