Preserving history: One museum’s mission

February 26, 2019

With a history known by few and preserved by fewer, the legacies of once bustling African-American communities in Bowling Green have faded with time. These communities are none other than Jonesville and Shake Rag, which remained Bowling Green staples from the early and mid-1800s, respectively, until around the end of the 1960s.

As the city expanded during this time, these communities slowly vanished, remembered primarily by those who called them home. In an effort to continue the legacies of both, an organization named the New Era Planning Association formed in Bowling Green in 2001 “to preserve the small number of historic buildings that are left standing in the [Shake Rag] neighborhood,” an NEPA brochure stated.

In 2011, the NEPA helped establish the African American Museum in Bowling Green as a nonprofit, originally located on State Street. Due to a lack of space, though, the museum was moved to a WKU-owned location on Chestnut Street by the roundabout known as the Erskine House and officially reopened in 2017. The museum rents the space for a modest sum and has received donations from various local entities such as the Bowling Green City Commission.

Nearly two decades since the arrival of the NEPA, the organization’s initial mission is now entrusted to the museum. Packed with remnants of Bowling Green’s African-American history, including medals from Bowling Green African Americans who served in the United States military, copies of yearbook photos from some of the city’s long-closed segregated high schools and artwork from WKU’s first African-American prom queen, the museum breathes life into a largely overlooked narrative.

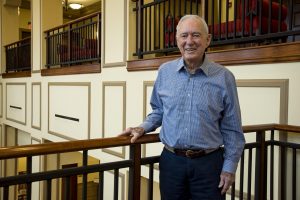

John Hardin, former assistant dean of Potter College, Assistant to the Provost for Diversity Enhancement and WKU history professor, serves as chairman on the museum’s board of directors. He said the museum offers a look into the history of African Americans in Bowling Green, which it hopes to share with anyone interested in learning more. “We want the public to come to give some sense of the African-American contributions to the community,” Hardin said.

Hardin elaborated on these contributions by mentioning the Shake Rag area’s influence on ragtime music and its status as a social hub throughout the 20th century. He also noted the importance of religious and educational institutions during this time period, such as the State Street Baptist Church and State Street High School, with the latter featuring graduates who later went on to become some of WKU’s earliest African-American students.

Though WKU, then known as Western Kentucky State College, began accepting African-American students during the 1950s and 1960s, Hardin said this was not without its challenges.

“There were instances of segregation, there were instances of discrimination,” Hardin said. “But the African-American community and its members made the best of a difficult time and were able to succeed despite, not because of, racism.”

He said he believes a fact like that is worthy of keeping in mind. Without the knowledge of both the struggles and successes African Americans encountered in Bowling Green during a time in which communities like Shake Rag and Jonesville were effectively wiped away in the name of citywide expansion, Hardin said it’s vital to recall the past in ensuring the future may be better.

“We have to remind people of where we’ve been so we don’t go down that ugly path again,” Hardin said. “That’s why places like this are important.”

Hardin added he believes it’s the place of historical institutions like museums to serve not only a function of preservation but also one of instruction.

“Museums are necessarily educational institutions but without classrooms and without tests,” Hardin said. “They’re meant to educate the public.”

Though the museum does its best to do just that, Hardin said almost all of its staff members are volunteers, including the museum’s seven board members, which often makes business difficult. With this, Hardin said one of the museum’s largest obstacles currently is branding itself sufficiently.

“Some of us on our board are learning the whole business now of dealing with all of this,” Hardin said. “It’s not easy.”

Due to this, the museum recently began collaborating with WKU-affiliated advertising and public relations agency Imagewest for rebranding services, including a minimal logo redesign and help with the museum’s online presence. Hardin said he believes these changes are necessary to keeping with modern expectations.

“The challenge is we have to sort of keep in touch with what delivers,” Hardin said.

Bardstown junior Sarah Starkey, who works as a leading account executive and writer at Imagewest, said Imagewest has collaborated with Hardin and the museum since a week before the beginning of the semester.

Starkey said the agency is currently creating a website for the museum with a GoFundMe page to help increase revenue and make future renovations to the museum’s exhibits more manageable. She added the agency is creating promotional materials such as posters, flyers and a virtual tour animation for the museum’s website along with rebranding the museum’s logo, too.

After speaking with one of the museum’s volunteers, Wathetta Buford, who grew up in Shake Rag, about how she misses the restaurants and sights that once belonged to her childhood neighborhood, Starkey said she was moved.

“If you just go and sit and talk with any of the board directors, they will tell you amazing stories,” Starkey said, going on to recall her specific interaction with Buford. “Just listening to her testimonial about all that was heartbreaking.”

Starkey said she believes it’s unfortunate so little remains of Shake Rag and Jonesville’s vibrant histories but is happy to work with those who remember the communities for all they were. However, she said she knows the museum will need support beyond Imagewest if it is to succeed.

“They had some amazing contributions but nothing really to memorialize them,” Starkey said about the city’s historic districts. “It’s definitely nice to be able to bring them back to the light, but at the same time, it’s hard to do that without a lot of support from the community.”

If nothing else, Starkey said she believes a visit to the museum is rewarding in ways one might not expect. She said she encourages anyone interested in African Americans’ impact on the city to stop in and meet those who can explain it best.

“I definitely think it’s worth it to go up there and talk to them,” Starkey said. “That’s something that I think is very important.”

As the museum is one of few similarly focused heritage centers throughout Kentucky, Hardin said he believes the history of African Americans specifically in Bowling Green is a story still worth preserving. Now located only three or so blocks away from where Jonesville once thrived, Hardin said, he believes the museum will serve a profound purpose in keeping alive Bowling Green’s rich African-American culture for all those who care to know.

“It has its own series of stories and heritages that have to be addressed,” Hardin said about the city. “Our goal is to, first of all, recover, document, preserve and present the history and culture of African Americans in the Bowling Green area.”

To this point, the museum has attracted various local groups and public schools. With plans to soon lead some WKU classes on tours of the museum, as well, Hardin said it looks to continue expanding its reach, which it will attempt to do in

June alongside the Aviation Heritage Park in Bowling Green when it honors Glasgow native Willa Brown, the first African-American woman in the United States to earn a pilot and commercial license, according to a gallery on the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum website.

Tours may be set by appointment through contacting the museum at its phone number. Tours are free of charge, as well, and the museum is open to donations of all kinds.

Despite more than 50 years between today and Jonesville and Shake Rag’s prime, Hardin said he believes Bowling Green maintains a special connection to its African-American roots.

“It’s one of cohesiveness, working together, community, people,” Hardin said. “There is a sense that there is a need now more than ever for the community to work together to address issues.”

Reporter Griffin Fletcher can be reached at 270-745-2655 and [email protected].