EDITORIAL: Confederate site marker on campus is information, not a celebration

February 26, 2019

Issue: WKU’s Student Government Association is creating a resolution to remove a Civil War marker located in front of the Kentucky Museum which recognizes Bowling Green was the Confederate State’s capital of Kentucky.

Our Stance: The Civil War marker does not honor the Confederacy but instead simply acknowledges a dark part of Kentucky’s history that both WKU students and Bowling Green citizens should be aware of.

The controversy surrounding the removal of Confederate monuments in southern states has been a hot-button issue recently, as many people have made the case rebel soldiers who fought to keep people of color enslaved should not be dignified with a statue.

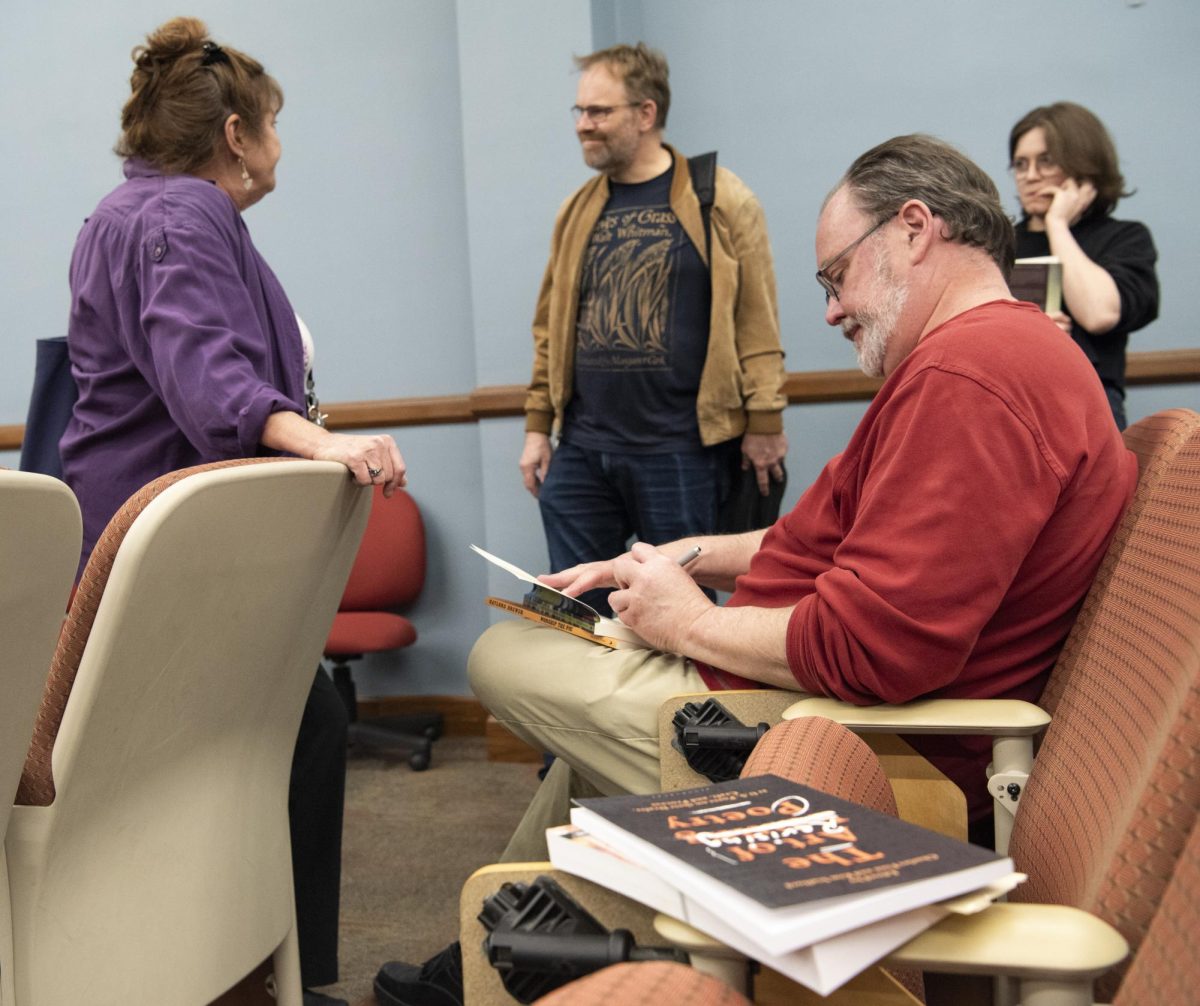

Last week, WKU SGA senators Conner Hounshell, Symone Whalin and Kara Lowry announced they will begin an attempt to remove the marker in front of the Kentucky Museum that states Bowling Green was the Confederate capital of Kentucky at one point during the Civil War.

Herein lies the problem: the marker is not a monument, but a sign.

This marker does nothing to celebrate the Confederacy in any way. It only displays an objective fact which everyone living in Bowling Green should be aware of.

While Confederate statues may evoke a sense of reverence and praise, this sign informs people of an abhorrent time in American history which is too often either glorified or concealed. Germany has multiple monuments across its country dedicated to the Holocaust, but none of them are a celebration of what happened during World War II. These monuments remind people of atrocities that occurred and the victims they impacted. Any Civil War marker involving the Confederacy should do the same.

Bowling Green may have only been the Confederate State’s capital of Kentucky for less than five months due to the United States Army later taking control of the area in February 1862, but this still means there was a plethora of Confederate sympathizers in the city.

This culture did not just evaporate once the Union gained control of Bowling Green, and racial problems across America show this is an obstacle other states must deal with too.

Bowling Green was home to many African Americans following the Civil War, as well. The Shake Rag district began developing in the early 1800s, and after the war, it became a viable area to live for hundreds of African Americans, according to the Bowling Green Area Convention & Visitors Bureau’s website.

Jonesville—a black community formed in Bowling Green after the Emancipation Proclamation—was formed by freed slaves and existed for nearly 100 years in area that is now the bottom of WKU’s campus, according to the Kentucky Historical Society’s website.

The property of Jonesville was bought by the state government in the 1960s after it decided the area needed an urban renewal. This gentrification led to the displacement of hundreds of African Americans who had formed a well-functioning community amid people who did not view them as true Americans because of the color of their skin.

Jonesville had to be formed because there were people who lived in Bowling Green who believed people of color shouldn’t be able to live their lives as they saw fit. Confederate sympathizers in Kentucky did not want African Americans to be freed from chains, nevertheless to be their neighbor.

Kentucky’s racial issues certainly have not stopped since the gentrification of Jonesville, either.

In Louisville in October 2018, Gregory Bush attempted to break into a black Baptist church only to fail and then proceed to kill two African Americans in their late 60s (both of whom were grandparents) at a nearby Kroger supermarket. Before leaving the scene, Bush told a white male, “Whites don’t kill whites.”

In 2017, the FBI stated hate crimes reported in Kentucky had risen 83.5 percent.

It is not only easy but also comforting to believe America has moved past the horrors of racism. But the easy, comforting thing to believe is rarely the truth.

Instead of as a sign of hate, the Civil War marker in front of the Kentucky Museum should serve as a reminder to everyone who passes it that America is still dealing with the fallout of deplorable events which took place hundreds of years ago, and that, as a nation, we still must work together to try and heal those wounds.