Documents show WKU subsidizes athletics at highest rate in Kentucky

April 28, 2016

Dollar for Dollar

Recently released documents show that WKU has increased its subsidy for the athletics department for a second consecutive year.

Each fiscal year, every NCAA athletics program with Division I status must file a financial report to the NCAA detailing total operating expenses, revenue and money received through direct institutional support.

Subsidies are taken out of WKU’s general fund — money otherwise spent on endeavors such as raising the quality of education WKU offers. One big criticism against intercollegiate athletics is that these subsidies pay for an athletics program with no intrinsic academic or educational benefit.

While the NCAA does not publish individual reports from all 231 programs, the financial reports that are published fall under public domain and offer a sobering look at the cost of intercollegiate athletics.

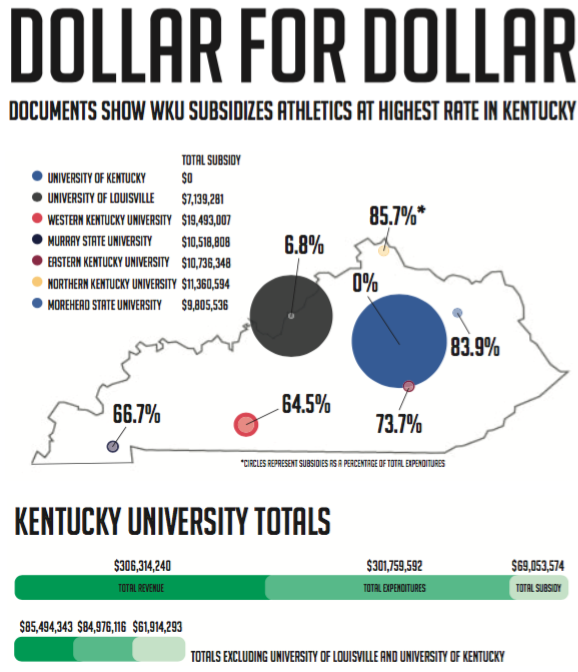

According to documents filed to the NCAA from all seven universities in Kentucky with Division I status, no university subsidizes athletics dollar for dollar more than WKU.

Of the WKU athletic department’s $30.2 million operating budget from 2014-2015, a staggering $19.5 million was required in subsidy from WKU’s general fund just to break even. Of WKU’s athletics budget, 64.5 percent comes from money not made through athletics.

To put that in context, after the $19.5 million in subsidy from WKU, the next highest subsidy in dollar amount belongs to Northern Kentucky University at $11.4 million.

This trend isn’t getting any better, either. WKU athletics’ dependence on money is only growing.

During WKU’s last year in the Sun Belt Conference from 2013 to 2014, the program totaled an operating budget of $27.7 million and required a $15.8 million subsidy — 56.9 percent of the athletic program’s operating expense — from WKU.

Now, three years later, the athletic budget’s total expenditure has increased to $30.2 but requires a larger 64.5 percent subsidy of $19.5 million.

The Herald tried to contact associate athletic director Craig Biggs for any comments on the matter, but Biggs was not able to comment at the time of publication.

Joe Cobbs, sports economics and marketing professor at NKU, believes these subsidies from universities aren’t simply colleges wasting money on athletics.

“One way these investments pay off is just getting into the minds of high school kids, especially when it comes to to these bowl games and tournaments. If a school is making a profit off their program, in many aspects that’s just capitalizing on advertising,” Cobbs said, referring specifically to NCAA tournament runs made in the past decade by WKU, Murray State University and Morehead State University.

“You have [high schooler students] that begin to make their lists of where they might go,” Cobbs said, “and a lot of the time, the schools that end up on these lists are schools that kids don’t only recognize from TV, but that they recognize as having a strong brand.”

Cobbs said while there isn’t a direct correlation between the success of an athletics program and the quality of education offered at its university, the two notions hypothetically go hand in hand.

“Theoretically, you could bring in better students. By raising the profile of the university, you bring in more applications and ideally could be more selective of who you accept,” Cobbs said.

Yet this still begs the question of where universities’ priorities lie when they subsidize athletic programs. The entire objective of higher education is to educate the masses, not to create the most profitable sports programs.

Other experts like Brian Goff, distinguished university professor of economics at WKU, see intercollegiate athletics for what they are: professional-grade sports entertainment programs.

Goff’s office, filled with well over 30 years of his career, is impressive. A bookshelf wraps around one side of the professor’s office, which is nestled in a corner on the second floor of Grise Hall.

His books “The NCAA: A Study in Cartel Behavior” (1992) and “From the Ballfield to the Boardroom” (2006) cover the economics of intercollegiate athletics, a topic he writes about frequently as a contributor to The Sports Economist and Forbes.

Goff flipped from tab to tab on his Internet browser, sifting through his own articles relating to the NCAA’s economic impact on universities.

After a prolonged glance at a recent Forbes piece he wrote and a mere nod at another that ran in The Sports Economist, he reclined to his original sunken demeanor as if carefully mapping out each word he was about to say.

“Most of the system’s biggest critics find that the finances are where the problem lies,” Goff said. “That is simply not the case; the problem is within the system.”

He suggests the solution isn’t just to eliminate sports from higher education. There are far too many financial interests at stake. Goff does, however, question why these programs don’t function financially independent of their parent universities.

“It is a not-for-profit world in terms of running these programs, and when an athletics department creates their budget, they know it is in the best interest of their department to use those funds; otherwise, they won’t be there next time around,” he explained. “It happens in athletics, and it happens across all college departments, but no other college department functions as athletics does.”

Goff compares most mid-major and Power Five programs to be on par with professional sports franchises in terms of economic scale and commercial opportunities.

“You have two worlds that have merged. One where, if a team makes 200 million dollars, the players are going to get 100 million of that,” Goff said. “In college sports, athletes aren’t even getting close to that no matter how you add up scholarships and other benefits.”