WKU striving to improve diversity

April 27, 2012

Born and raised in upstate New York, Richard C. Miller grew up in an integrated environment with plenty of white friends.

For his undergraduate degree, Miller attended Ithaca College, a predominantly white institution.

But it wasn’t until he took a professorial job at Bowie State University in Maryland, an HBCU — historically black colleges and universities — that he was ever in an environment that was predominantly black.

“I really developed a strong sense of identity with my own race that I really hadn’t had a chance to develop prior to going to Bowie State, which was really important to me educationally, socially,” he said.

Since Bowie State, Miller has worked at Ithaca College and Benedict College in South Carolina — an HBCU.

Miller became associate vice president for Academic Affairs at WKU six years ago but was also asked to also serve as the first chief diversity officer by President Gary Ransdell in 2007.

His own life experiences have taught Miller, now vice provost and CDO, about the similarities, differences and prejudices of both white and black people, he said.

In his role as the CDO, Miller is responsible for monitoring the university’s progress on diversity-related issues, including requirements set by the Statewide Diversity Policy, which seeks to enhance diversity in postsecondary education.

This plan sets the parameters for each institution to establish its own plan, Miller said. As an example, Miller said Eastern Kentucky University or Morehead State University may choose to focus more on socioeconomic diversity because of the economic environment in that part of the state.

“The policy is broader,” he said. “It does give more flexibility to the institutions to define diversity as it relates to its own plans, and it takes into consideration the service areas for the institutions.”

This new policy replaces the Kentucky Plan, which only focused on black students who were from Kentucky, Miller said.

WKU’s diversity policy says diversity can include but is not limited to “race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, religion, color, creed, national origin, age, disabilities, socio-economic status, life experiences, geographical region or ancestry.”

However, the eight categories that WKU works toward for state requirements measure the success of minority students and the number of minority faculty hired.

“If you fail to show that you’ve met six of the eight objectives, then the institution is no longer able to offer any new degree programs, and that is a huge incentive,” Miller said. “So we watch these numbers very, very closely.”

The objectives are: undergraduate enrollments; graduate enrollments; first-to-second year retention of undergraduates; second-to-third year retention of undergraduates; baccalaureate degrees conferred; employment of executive, administrative and managerial staff; employment of faculty; and employment of other professionals.

According to a degree program eligibility status report from February, WKU met seven of the eight objectives for the 2010-2011 calendar year, showing progress in every category but first-to-second year retention of minority students.

In the fall of 2009, WKU retained 399 of 580 minority students for their sophomore year. But in 2010, that number fell to 390 out of 594.

Miller said this is an OK start for the first year of policy implementation, but he would prefer the university achieve eight out of eight objectives.

Every institution at least met the required six of eight objectives, Miller said.

Going forward, WKU’s diversity policy looks to gradually increase the number of minority students enrolled and graduating from the university, as well as increase the number of minority employees on campus.

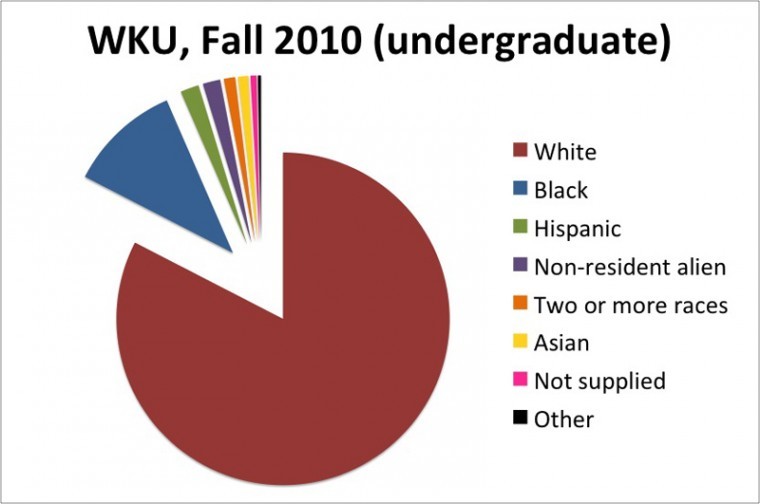

For example, the undergraduate population at WKU was 10.9 percent black in fall 2010. By fall 2017, the plan strives to be at 11.5 percent.

Although the elimination of Bowling Green Community College and higher admissions standards have reduced the number of minority students admitted to WKU, Miller said the students that are admitted will be more academically prepared for college.

As for attracting high-achieving minority students, Miller said WKU is “recruiting with one hand tied behind our back.”

“My concern is that we are not attracting the high-academically-capable minority students, especially African-American students,” he said. “We’re not. Other institutions are doing a better job of attracting the high academic ability — the minority students who have ACT scores, high 20s, low 30s, 4.0 GPAs. I’m not satisfied with our ability to attract those students to WKU.”

The university is looking at ways in which it can address that issue, he said.

“Some institutions, when they go out and recruit, they have scholarships right in hand…And when they come across a minority student who qualifies, they’re offering them scholarships right there,” he said.

“We don’t do that. We say, ‘We’ll take your name, and you apply, and we’ll come back, send your name back to WKU, sit down in a meeting, and we’ll determine… We’re not competitive if other institutions are offering scholarships right on the spot.”

But for now, many of the minority students admitted to WKU are at-risk academically. In the fall of 2011, 697 of the 2,179 black students admitted to WKU — 32 percent — had to take at least one class at South Campus.

Sherry Reid, who retired as dean of Bowling Green Community College in 2010, said that going forward, WKU should think about what the students need to succeed and then make sure the necessary resources are in place for that to happen.

Students need to know how to organize, manage their schedules and do homework, she said. Vee Smith, assistant director of the Office of Diversity Programs, and Howard Bailey, vice president for Student Affairs, have been crucial in providing support to at-risk students, she said.

“I think if you’re going to admit students, then they have to be a priority,” she said.

Although some people at WKU resent money being spent on students who aren’t college-ready, Reid said programs and faculty support are crucial in helping students.

“Some will fail in spite of what you do — that’s human nature, but they shouldn’t fail because we didn’t provide what they needed,” she said.

Bailey, who has studied race for the last three decades, said despite all the pitfalls, WKU is leading the way on improving diversity and supporting minority students.

“And we’re doing a better job at this subject than most of our colleagues at the other institutions,” he said. “As much as we need to improve, I feel like we do better than the other institutions around the state.”

Bailey is right — WKU has more black students than all of the public universities except for the University of Louisville and Kentucky State University, an HBCU.

Miller said although many of WKU’s minority students are at-risk, this doesn’t mean they should be judged by their academic profiles.

“I’ve worked at two historically black institutions before coming here, and so I’ve seen first-hand minority students who are exceptionally bright and capable,” he said. “When I look at South Campus, that’s what I see — I see a lot of students who have exceptional capability, even though they may be academically at-risk.”

*Editor’s note: This is part four of a four-part series.