Family, friends of WKU graduate build foundation after son’s suicide

September 30, 2011

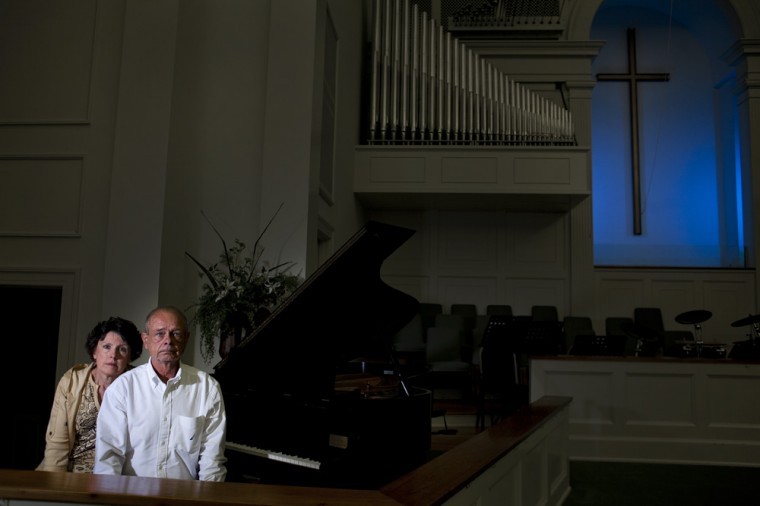

Six years after her son’s death, Sandy Drake said what may hurt the most is that her son’s suicide was “absolutely preventable.”

“All of the pain Eric was feeling, he isn’t feeling it now, but we are,” Sandy said. “We don’t have Christmas anymore. We used to have big Thanksgivings. Now, I don’t want any birthday presents. I’m fine if no one wishes me a happy birthday.

“I don’t even want to hear it, because it isn’t happy anymore.”

Drake received a call from her son, Lee Eric Drake, around 1 p.m. on Feb. 3, 2005.

The 24-year-old called to tell both his mother and father he loved them just before he took a gun to his head and pulled the trigger in the kitchen of his parents’ home.

Eric was a 2004 WKU graduate, former Big Red, Pike fraternity member and talented musician before he took his own life after suffering from severe depression less than a year after graduating.

Six years later, his suicide still haunts the Drake family every day.

“This is the kind of thing that shakes every bit of your foundation – every bit of who you are,” Sandy said. “This never ends. Your body goes through so many emotions you didn’t even know you had. It starts in your head and goes through the bottom of your feet. It is the depth of the low. The very depth of low.”

His funeral, which was held on Super Bowl Sunday in 2005, was attended by hundreds of people Eric had known during his life. Friends, former teachers, even employees of stores where Eric had shopped wrote letters to Sandy, her husband, Don, and their oldest son, Ben, telling the family what an impact he had made in their lives.

On the night of his funeral, seven of Eric’s friends created a foundation in his name to spread information to others that they lacked until they sought answers after his suicide.

Eric was known as outgoing, fun and a witness of religion to his fraternity brothers, but that all began to change after he graduated in May 2004 with a major in geography and emphasis in meteorology.

A few months after graduating, Eric struggled to find a job. That summer he began working at the airport in Bowling Green, but something about him had changed.

“Eric had a lot of pain in his life,” Sandy said. “It is nothing he wanted. He woke up with it, like a person who wakes up with cancer one day. We try to minimize how hard people’s days really are. We tell them they are going to be fine and don’t really listen.”

“Eric tried to tell me something wasn’t right, and I told him it was just a phase he was going through.”

His condition steadily grew worse when Sandy said she noticed her son starting to lose weight, stop eating and become paranoid. His hair wasn’t kept, and he gave up on shaving. The once outgoing, loving son and friend continued to spiral downward when he stopped visiting and talking to people altogether by November.

Eric’s changes were so drastic that Sandy said people didn’t recognize her son in stores when they passed by.

In December, Eric saw a psychiatrist but refused to say a word to the doctor. By January, he had admitted himself into Parthenon Pavilion, a mental health facility in Nashville. Three weeks later, Eric’s insurance was depleted, and he was sent home and “supposedly cured,” Sandy said.

Sandy said the family received no instruction and no mandatory follow-up appointment, but were simply told to treat their son as if he had just had major surgery.

However, Sandy said they weren’t told that Eric had been on suicide watch, which means he was checked on every 15 minutes since he had arrived at the psychiatric hospital – knowledge that wasn’t obtained until after Eric’s death.

“I thought I knew how to take care of someone who has had surgery before,” Sandy said. “That’s one thing, but if someone says, ‘Your son or your boyfriend is suicidal,’ that changes everything.”

They didn’t know that research shows a majority of people between the ages of 18 and 24 experience chemical imbalances in the brain, which can lead to suicidal thoughts and actions like their son was experiencing. They didn’t know they were entitled to their son’s medical records and that he had signed to share the information with his family.

With the lack of knowledge and information provided by the facility to the family, the Drakes sued and settled outside of court.

Dan Padgett, one of Eric’s best friends from Hopkinsville and board member of the Lee Eric Drake Foundation, said because mental illness isn’t talked about openly, many people don’t understand.

“Suicide is such a taboo subject. We don’t talk about it,” said Padgett, who was Eric’s fraternity brother and lived with him in college for five years.

“Eric was the most non -prototypical person to become a statistic for suicide, but here we are six years later and I’m still battling with the question, ‘What if?’ I didn’t know what warning signs to look for. I was the only friend who knew he was in the hospital, but in my mind, I just kept thinking, ‘He is going to be better when he gets out.’ Eric’s situation was real, and we didn’t realize it.”

Padgett said he doesn’t want other friends or families to have to struggle with the loss of their loved one through suicide, which is the LED Foundation’s goal.

The foundation’s goal is to lend aid to those who possess or are susceptible to psychological illness through direct help and awareness, especially in September, which is recognized as National Suicide Prevention month.

One way to accomplish those goals are through the LED Foundation’s scholarship fund, where $1,000 is awarded to a selected graduate student in the mental health field of study.

Students can apply online at leeericdrake.com by completing an application, as well as a 500-word essay, like one of the award’s most recent recipients, Janay Smith Atkinson.

Atkinson is a 2009 WKU graduate who is currently working on a psychiatric nurse practitioner degree at WKU in conjunction with the University of Louisville.

“Awareness is key in these particular scenarios,” she said. “Not one more life should be taken by suicide. These individuals should not have to suffer any longer or doubt their future. We can make a difference.”

A difference is exactly what Eric’s older brother, Ben Drake, hopes to accomplish through students like Atkinson, who plans to become a nurse specializing in mental health.

“When he had his illness, we didn’t talk about it,” said Ben, who now lives in Florida with his family. “Part of our mission statement now is to honor his memory by promoting awareness and contributing to the study of mental illness.”

Ben serves on the foundation’s board and helps determine whom the board should award the scholarship to each year. He said they hope to increase the amount with more donations.

“If we can help one person,” Padgett said, “It will be worth it.”