Overcoming it all: Clem Haskins shares experience of integrating WKU’s basketball program

Former Western Kentucky University basketball player Clem Haskins is interviewed by Kaden Gaylord-Day in Diddle Arena on Oct. 6, 2021. Haskins, along with teammate Dwight Smith, became the first African-American athletes to integrate WKU’s basketball program in the fall of 1963.

October 25, 2021

Two African American athletes joined the Western Kentucky basketball team in the fall of 1963 during the height of the civil rights movement. Their presence and success on the court helped kickstart change in American culture, society and history.

These athletes were Clem Haskins and Dwight Smith. The duo became the first black athletes in the south to integrate college basketball in a time of widespread racial hatred and prejudice.

Clem Haskins was born and raised in Campbellsville, Kentucky. The son of Charles and Lucy Haskins, he was their fifth out of 11 kids. Growing up on a farm, race wasn’t an issue like it was in town. His best friend, Dave Roberts, was white, and they were like brothers. They played together, ate together, and Roberts even taught him how to play basketball.

At the age of 12, he experienced his first encounter with racism. Haskins and Roberts went to town to watch a movie and sat together, thinking nothing of it. The usher made Haskins go upstairs to segregated seating and Roberts followed. The usher came back and made Roberts return downstairs, but the pair didn’t understand why.

A few years later in 1961, when Haskins became the first African American to attend Taylor County High School, he realized why he received that kind of treatment.

Haskins set a scoring record in his junior year of high school, putting up 55 points in Marrowbone, Kentucky. He was the only black person in the whole gym, a crowd of around 300 people. The hatred thrown at him motivated him to play at his best, to show that hate couldn’t stop him from being great.

“They were waiting for me, and they were going to lynch me after the game,” Haskins said. “It was kind of a scary time… I would say that’s one of the nights I was scared the most.”

Being a basketball player wasn’t supposed to be part of the plan for Haskins growing up. His parents were sharecroppers with a mindset of working to provide for their family, not sports, but still supported their son all the way through.

“My parents had a fourth and fifth grade education,” Haskins said. “Education wasn’t important to my parents, but they loved me as their son. They didn’t understand about college, they didn’t understand about sports. My dad never saw me play until I was a senior in high school. All my dad wanted me to do was get up and go to work. He didn’t care about sports, but he became a fan of mine after I came to Western. He came to most of the home games, and they supported me 100%.”

Dwight Smith, Haskins’ WKU teammate and close friend, was a native of Princeton, Kentucky. He played basketball at Dotson High School and was valedictorian of his graduating class before making his way to the Hill.

Both Haskins and Smith received numerous offers from different schools, including WKU, after being recruited by Hilltopper legend E.A. Diddle. Smith was the first of the two to commit to play on the Hill. Haskins originally committed to play for Louisville, but eventually changed his mind to become a Hilltopper and play alongside Smith.

“We kind of made a commitment to each other,” Haskins said. “We played in the Kentucky-Indiana all-star game. Dwight had already signed to Western and at that time I signed to go to Louisville. We were good friends, and we made a bond [that] we would go to Western together so that’s why I traded places, but I was recruited by Western [the whole time].”

The Jim Crow-era south was a scary place to be, but when it came to living on campus, Haskins and Smith enjoyed a different experience.

“All of the coaches were close, and they welcomed me… and the community accepted me as a black athlete,” Haskins said. “Of course, yes, we had problems when we left campus to go to other places, but here in Bowling Green, they treated me as another student and another person. We were respected. We had the respect of the administration, presidents, coaching staff, everyone we were involved with and that made it much easier for us.”

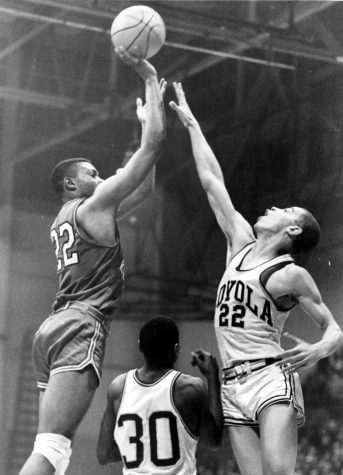

The two put up historic numbers together. For his college career, Haskins averaged 22 points and 10.6 rebounds per game. He was a three- time Ohio Valley Conference Player of the Year from 1965-67 and a First- Team All-American in 1967. His No. 22 Jersey was retired. Smith averaged 14.6 points and 11 rebounds per game and finished on WKU’s 1,000 points list before being drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers.

The duo won back-to-back OVC tournament championships together while making a big splash in the NCAA tournament. In 1966, the Hilltoppers were just two points away from beating Michigan and playing the University of Kentucky in the Mideast regional final. Haskins broke his wrist in 1967, preventing him from playing like his usual self, but WKU still won the OVC.

Both players finished their Hilltopper careers as members of the program’s 1,000 points club and made their way into the WKU Hall of Fame. Haskins was part of the inaugural class in 1992, and Smith was inducted shortly thereafter in 1995.

Haskins and Smith were like family. They were each other’s support systems in a time when the world was against them. Then tragedy struck. On May 14, 1967, Smith was in a horrific car accident that cut his life short.

“We became very close, like brothers. We were roommates. When he was killed… it was one of the saddest days of my life,” Haskins said. “It was a totally different world being a black athlete, playing in it, and being a black athlete at WKU. Because you look around and see no other black faces.”

Being an African American in the 1960’s also meant you couldn’t eat in the same restaurants, stay at the same hotels, drink from the same water fountains and receive the same education as white Americans. But when it came to being on the road and traveling as a team, the WKU basketball program did not make Clem feel like he was alone.

“I have to give my coach a lot of credit,” Haskins said. “I don’t think John Oldham got the credit he deserved for playing black athletes because I know he got hell [for it] and was criticized for being associated with coaching black athletes.”

Oldham took over the head coaching job from E.A. Diddle after he retired in 1964.

“He did a wonderful job of protecting us and treating us like regular players,” Haskins said. “He treated us like his sons and embraced us at times that we needed to be embraced because he knew what we were going through. It was not easy walking across campus, walking downtown, and in the community and hearing things that you don’t want to hear at seventeen years of age.”

As it’s written down in history, most players who integrated a sport, team or community had to deal with racism and prejudice from people within their own organizations. For Haskins, his teammates provided a sense of comfort in an uncomfortable and frightening situation.

“All the players I played with embraced us and they would go to war for us if anybody said anything,” Haskins said. “They would be the first one to fight our battle for us. We had no problems in practice, it never became a black versus white thing.”

In a time when activism was in the spotlight in the south, being one of the only black people on campus played a role in preventing Haskins and Smith from being voices for social change, something that black people get to be today.

“We didn’t have any one individual in the community that was doing that, but if they had marches back then, would I have been marching? Probably so,” Haskins said. “I think it’s great for young people to speak up. They should have a right to do that and not be scrutinized for that and I support them for that.”

Clem Haskins and Dwight Smith should be two names viewed in the same light as Jackie Robinson, Bill Russell and any other athlete that broke barriers in sport. The WKU basketball program went through trials and tribulations so that we all could be a part of the progressive nation we are today.

“Steve Cunningham, Vinton Pease, Wayne Chapman, Ralph Baker, Ray Rhorer, all the guys that played with me, I just want to thank all my teammates for supporting me through everything,” Haskins said.

In the face of adversity, racism and hatred, Clem Haskins and Dwight Smith set records and formed a brotherhood with white players in the south to show that love will always trump hate.

Men’s basketball reporter Kaden Gaylord-Day can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @_KLG3.