‘No single correct answer’: Climate change affects Kentucky

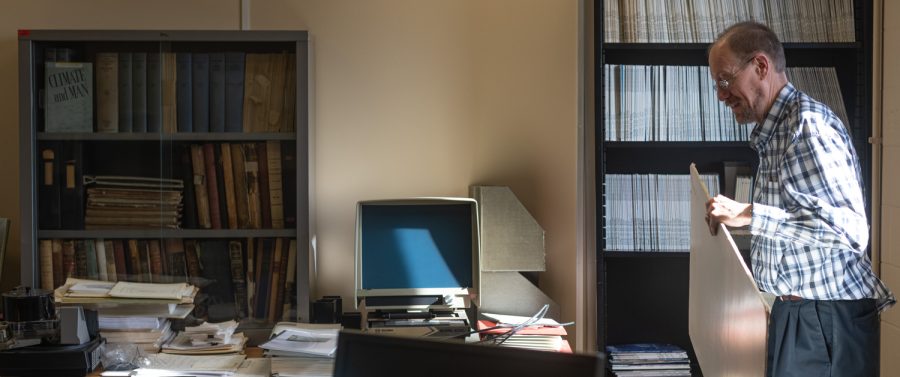

Western Kentucky University professor Jerald Brotzge (right), works with research assistant Caden Childers (left), to renovate and reorganize the room housing the Kentucky Climate Center on the third floor of the Environmental Science & Technology Building on Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2023 in Bowling Green, Ky. In addition to teaching at the university, Brotzge also directs the Kentucky Climate Center, which “provides climate services, conducts climate research, and engages students in projects that build upon classroom learning,” and the Kentucky Mesonet—an interconnected system of several weather monitoring stations throughout the state.

February 2, 2023

Raging flash flood waters took 43 lives, countless homes and businesses across eastern Kentucky and central Appalachia last July. A total of $85.1 million in Federal Emergency Management funding was approved for applicants, as the rural counties of eastern Kentucky suffered catastrophic losses due to the historic event.

The worst flooding event in recent history followed the rare and devastating tornadoes that raked across western Kentucky months before in December 2021, killing 80 people and destroying thousands of homes and businesses.

Nearly all scientists say the Earth’s climate is changing, outside of its natural shifts, due to human actions. The United States Environmental Protection Agency states the primary driver of this change is the burning of fossil fuels that leads to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, which trap the sun’s heat on the planet, raising temperatures and affecting all global systems.

Experts agree Kentucky is experiencing the possible consequences of climate change, like the rest of the nation. Well known for its natural beauty, situated on a vast cave system and housing hundreds of rural communities, the state is affected differently by changes in the climate.

Jerald Brotzge, Kentucky state climatologist, director of the Kentucky Climate Center, director of the Kentucky Mesonet and WKU professor of meteorology, recognizes the shifts in climate trends – and the difficulty in quantifying them.

The most well-known effect of climate change is global warming, which is an increase in the overall surface temperature of the globe.

In Kentucky, 125 years of climate records indicate various warming and cooling down periods, with the 1930s being the warmest decade, Brotzge said. The state has seen a warm up period since roughly 1980, experiencing three of the top five warmest years within the past decade.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, temperatures in Kentucky have risen by 0.6 degrees since the beginning of the 20th century. In the United States, more extreme temperature events are becoming more common. Unusually hot summer days and nights have become more common in recent decades, while unusually cold winter temperatures have become less common, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Brotzge said not to necessarily expect higher or more extreme temperatures at usually warm times. Rather than higher daytime highs, we will see increased temperatures during usually cool times, such as at night and in the winter. Brotzge said an atmosphere with more moisture “moderates temperatures to some degree.”

When it comes to other severe weather events like natural disasters, determining whether or not they are being affected by climate change is more difficult.

In December 2021, many areas of western Kentucky were hit by catastrophic tornadoes – including Bowling Green. Some people have raised the question of whether or not this could be attributed to a changing climate.

Unlike some extreme weather events that can be directly correlated to climate change, the connection between tornadoes and climate change is complicated. Brotzge said individual events like tornadoes are hard to place on the larger scale of climate change.

“We’ve not seen a documented increase or decrease in the numbers of tornadoes due to climate change,” Brotzge said.

He said this is due to the current limited perception of detecting specific and individual climate changes, and it is “almost impossible” to say any certain event is caused by climate change.

Weather Changes

One clear consequence of climate change is an increase in intense rainfall. As the atmosphere warms, it is able to hold more water – and then able to release more water as rainfall. Per degree Celsius of warming, the air is able to hold approximately 7 percent more moisture.

Brotzge said in the last 30 to 40 years, Kentucky has gotten much wetter, with three of the five wettest years occurring in the last decade – what he calls the “wetting of Kentucky.” Brotzge described these as “broad trends,” with variability coming with each year.

When looking at the climate record, there is a noticeable and gradual increasing wetness across the state. Brotzge said in roughly 1900, the state averaged 45 inches of rainfall per year, and the average now is 55 inches per year.

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, excessive precipitation creates the potential for severe flooding. As the Kentucky climate gets wetter, the frequency of flooding could increase. However, labeling natural disasters like the eastern Kentucky floods as climate change induced is difficult, Brotzge said.

“All that to say, we’re not necessarily seeing more severe weather across the state,” Brotzge said. “The floods are difficult to quantify. Given the broader trends, you could say that increased flooding would maybe be expected in a warmer and wetter climate.”

Brotzge said the main issue with determining the connection between natural disasters and climate change is due to limited climate records.

“We make our best guess based on our current observations, on how frequent or infrequent certain flooding events are,” Brotzge said. “Those are our best estimates. So when we have a 1000-year event that comes along, then we have to ask the question, is this truly a unique event? Is it that rare or is this something that could occur more frequently?”

Referencing both the eastern Kentucky flooding and recent Buffalo, New York, snowstorm, Brotzge explained that while current data is unsure, larger dynamics like climate change will impact these events.

“With each of these, it’s a lot of local features that contribute to the event, but there’s always broader scale dynamics, impacting that event as well,” Brotzge said.

Climate change isn’t only researched through trends in weather systems. It is researched throughout various fields, especially in a state like Kentucky, where what is below the ground can provide detailed insight to what is happening above it.

William Haneberg, state geologist, director of the Kentucky Geological Survey and research professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Kentucky, explained his approach to understanding climate change.

“Basically, it comes down to energy,” Haneberg said. “That’s what drives a lot of storms, oceans warm and store a lot more energy and create larger damaging storms, when it comes to hurricanes, when it comes to rainfall […] the very cold period we had right around the holidays.”

Some misconceptions occur when climate change results in events, Hanesberg said, like snowstorms, arctic blasts and extreme cold, since many think climate change must equal global warming.

He explained that jet streams, narrow bands of strong winds in the atmosphere, are normally well contained, but warming in the Arctic impacts their function, like letting go of a “hose that’s under high pressure.”

“Even when it’s colder, that can be due to a destabilization of the climate system and things not happening where they’re supposed to happen,” Haneberg said. “At the same time it was incredibly cold here in Kentucky, it was unusually warm across Europe and in parts of the Arctic. So they’re linked together. Basically, it’s energy that drives storms of all kinds and drives winds, and we’re basically accumulating energy in the form of heat, especially in the oceans.”

Haneberg said we are seeing differences in the frequency of flooding, referencing the floods in eastern Kentucky as well as the floods in Beattyville, Kentucky, two years ago.

“We’re starting to see in a lot of places, floods that are much larger and much [more] common,” Haneberg said.

Geologic Patterns

Jason Polk, WKU professor of geoscience and director of the Center for Human GeoEnvironmental Studies, said to expect shifts in weather patterns under climate change.

Like Haneberg, Polk said erratic weather could become more common. As more data is collected about recent climate patterns, this will become more visible.

“Like you see now where you’d have anomalies, where just once in a while you might see a 70 degree day in January, but more consistently, you’ll see those types of changes in patterns where you wouldn’t expect it based on historic weather data,” Polk said. “[…] you build those data sets [and] you’re able to actually see those trends, long term, since climate [is] decades and longer, not just day to day or season to season.”

Polk said current climate reports and research are pointing to shifting weather patterns, but there is no “single correct answer” to predicting catastrophic weather events we’re seeing. Despite this, Polk believes we still need to find ways to alter and deal with climate change, especially on a community level.

“We know that those [climate patterns] are sort of exacerbated and happening a little more quickly, [in] some ways, [to] what we would expect naturally,” Polk said. “Therefore, all the science points toward us doing things in whatever way possible we can to help mitigate the effects of climate change.”

One unique natural feature about Kentucky is the state’s abundance of caves and sinkholes. In these geologic formations, Polk is able to view localized climatic impacts in the form of carbon dioxide cycling.

Dissolving limestone rock can potentially remove carbon from the atmosphere, or act as a carbon sink, Polk said. As the leading greenhouse gas, understanding carbon dioxide cycling is essential to decreasing its effect on the atmosphere.

“We’re just trying to quantify another part of that carbon dioxide to the greenhouse gas cycle, which then we can then do in other areas,” Polk said. “Then once we have a good method, we can then expand that out to really look at bigger areas, bigger regions and really start to get a handle of what that process looks like.”

Polk said things like building houses and paving roads can disrupt carbon cycling, which can impact its role as a greenhouse gas.

Using various sources, Polk is able to reconstruct decades of climate data. In caves specifically, mineral formations that form from dripping water have layers, similar to tree rings, that can be used to reconstruct rainfall, temperature and vegetation data.

As eastern Kentucky experienced severe flooding and heavy rainstorms, scientists from the Kentucky Geological Survey mapped out over 1,000 new landslides in the area.

“There have always been landslides in the Appalachians and there always will be,” Haneberg said. “But when we have these very large, rare, unprecedented storms and they’re becoming more and more common, we’ll see more landsliding, we’ll see more erosion and sedimentation problems along riverbanks.”

Haneberg referenced floods that used to occur within large time frames could occur on much smaller time frames, such as a “500-year flood becoming a 200-year flood.”

“It’s not that they weren’t inevitable before – they would have occurred, but what we find is that events of a certain severity may become more common,” Haneberg said.

Recent flooding in Kentucky could be a representation of this. Haneberg assured that more severe events will not be more common, it is just that they will happen more frequently.

“Within the context of human civilization, and the very narrow band of climate conditions that we have developed as human beings, we’ve become accustomed to certain frequencies of events,” Haneberg said. “What other scientists think we’re going to start seeing is not that we’ll see events that were bigger than anything we’ve seen before, but that they’ll occur more frequently.”

Alongside frequency increases, climate change could cause weather events to be intensified, Nancy Gift, Berea College Compton chair of sustainability said.

“It’s always a matter of intensity,” Gift said.

“The rain that drops four inches in an hour might have dropped two inches in an hour pre climate change. We expect that basically every weather event is in some way intensified [to] some extent by changing climate.”

Gift said conditions classified as extreme some decades ago could be lower than extremes now, such as a 95 degree heat wave 30 years ago being a 105 degree heat wave now.

She said, going forward, climate change will cause us to “expect the unexpected” more often.

These unexpected – and often catastrophic – weather events suggested by climate shifts affect the livelihood of many Kentucky residents. As much as climate and sustainability experts suggest ways to mitigate risk, these methods may not always be feasible, especially for rural communities

“In flood prone areas, people will have to make decisions,” Haneberg said. “They’ll have to get used to more flooding. They’ll have to spend money to delegate things, and then sometimes you’ll hear people say, ‘well, the climate is going to change, it’s going to be inevitable. We’ll just adapt.’ And that is one strategy, but it can also be a very expensive strategy.”

Rural Kentucky

The divide between climate change preparation in rural and urban communities is clear, Gift said. For example, cities often have more housing regulations, which could include more sustainable heating and cooling systems, as well as insurance covering natural disasters.

In rural locations, this is not always the case. Building codes that determine insulation use in houses and energy use are often considered to be within city planning, Gift said. For residents in mobile homes or those who build their own houses may lack the insurance or decreased energy expenditures seen in larger cities.

Gift also explained a lack of public facilities limits opportunities for shelter from natural disaster, if the need arose.

“I think another thing for people in rural areas is that there aren’t often the same number of public buildings or facilities that would enable people to have shelter or backup, in case of a problem,” Gift said. “There might not be a community gymnasium where people could go shower, whereas like Winchester or Lexington would have some sort of Parks and Recreation type thing.”

Not only are rural residents’ homes less efficient, but their communities lack locations to cope with climate disasters, Gift said.

Gift described the quickest solution to climate change is energy efficiency. Yet from an economic standpoint, taking more sustainable measures against Kentucky climate change could mean altering one of the state’s well-known industries – coal mining.

According to the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, the Kentucky coal industry employed 4,628 residents statewide. Gift recognizes the belief of coal’s influence on the state’s economy, but explained that the money earned is often not cycling within the community that made it.

“[If] you’re looking at coal energy, it typically just comes in, it goes to the owner of the coal company who may not even be local in the first place,” Gift said. “That money comes in, it doesn’t really cycle and stay as well as renewable energy dollars tend to.”

With more sustainable measures, such as investment in renewable energy sources, Gift said money earned will stay in communities longer.

“It’s really partly about the recycling of money within communities,” Gift said. “So we need to do a lot more to make sure that the dollars spent in Kentucky stay here. Interestingly enough, that economic change will also result in some sustainability changes.”

Coal is not the only uniquely Kentuckian industry affected by climate change. Agriculture, which is the livelihood of many residents, is shifting due to the warmer and wetter climate, Hanesberg said.

Haneberg stated that alongside much warmer temperatures, agriculture will be changed by rainfall periods that are heavier and come at less ideal times, occurring less evenly throughout the year, according to weather projections.

“We’ll actually get more rain in the spring,” Haneberg said. “We often don’t need it because that’s maybe when farmers are out planting fields, and if you’re involved in farming the last thing you need is heavy rainfall to plant your crops.”

Haneberg said disproportionately hotter and drier temperatures also affect crop growth. Rather than focusing on increases in average temperature or average rainfall, the issue is found in these events occurring when they usually do not.

As climate change projections show influence on rainfall and warm temperatures, other natural features could also be affected.

Kentucky is also known for its bourbon industry, which might be affected by forest changes, Haneberg said. As bourbon is aged in white oak barrels, oak forests that are stressed could limit the capability of the industry.

“What happens if the climate changes enough, if these forests are stressed and maybe the oak isn’t as good as it was before, or the oak trees are prone to insects or diseases,” Haneberg said. “That’s being a little bit out there, because there’s no proof that this will happen, but [this is] in terms of scientists thinking ‘okay, here’s what we know. If this trend continues, what are the things that could go wrong?’”

Although this research is new, recognizing climate change patterns that are detrimental is essential not only to the planet but to our economy. By researching climate trends, Kentucky is able to proactively start risk management.

“Then the question is, well, what are the potential costs, or what are the financial damages and what are we willing to risk?” Haneberg said. “Like a scientific equivalent of going to Las Vegas, and you always have to ask yourself, what am I willing to lose if the dice don’t roll correctly?”

‘There’s still a lot we can do’: Climate Change Solutions

The real influencing power on the climate is on a larger level than our individual actions and communities, Gift said. Along with changes on a corporation and company level, plans to slow the effects of climate change sit in Washington – and Frankfort.

“It’s really, really important that we think at that larger systems level, because so much of the climate, so much of our energy use is happening by large companies, and we can’t alter that easily,” Gift said.

Gift also explained that the quickest solution is making the state, nation and globe much more energy efficient, beginning at a federal level and descending to each individual.

When it comes to individual and community preparation for natural disasters, Brotzge said it comes down to mitigation of risk, which could mean anywhere from stocking food pantries to installing tornado shelters.

“In the case of winter weather here in Kentucky, we don’t get that much. We average six inches of snow per year,” Brotzge said. “How much should we as a community invest in snow plows? At the same time, when those events happen, they’re very high impact. So much is weighing the risk of say, an EF-4, EF-5 tornado hitting the community versus how much do we want to invest in that. There’s still a lot we can do.”

Through investment and progress made in weather observations and meteorology services on a state and national level, the number of fatalities from natural disasters has decreased “by tenfold,” Brotzge said.

Brotzge said although there are more steps to making Kentucky safer due to these events, he is proud of the state for its investment in weather observation. It is the data provided by weather radar and the Kentucky Mesonet that leads to a safer community.

“That’s really the first step in making our community safer,” Brotzge said. “Because those weather observations provide what we call situational awareness, and if the emergency managers in the National Weather Service are blind to what’s occurring in the field, then they’re not able to issue those warnings in time.”

A flood monitoring network has been developed in Bowling Green, Polk said, which will provide data on flood levels throughout the city. As this project progresses, this data can be used to see flooding trends in certain locations, allowing residents to understand precautions to take against the certain level of threat.

“We can say, ‘okay, what can we do now to stay safe and prepare ourselves against whatever happens until we know [what] that looks like and have enough information to maybe do something on a bigger scale to be proactive and make the change,” Polk said.

After this, climate protection can be integrated into building planning and used to address preparedness level.

The best course of action is looking at different kinds of severe weather and recognizing how climate change impacts human vulnerabilities – beginning at the local level, Polk said.

“If you can’t stop what’s happening fast enough, then the thing you need to do really is to try to build resilience, to try to adapt and come prepared,” Polk said. “Whatever it might be, whether it’s going to be tornadoes or floods or severe cold. You need to do things to prepare people, make them aware, educate them, then be prepared in whatever case, whether it’s to do assessments or to do things to help community support and development […] if we can do that, it will help us survive and weather the storm, no pun intended.”

Content editor Alexandria Anderson can be reached at [email protected].