Blacked out: Redacted sexual misconduct files obscure nearly a decade of university Title IX actions

September 20, 2021

After a four-year legal battle and a Supreme Court decision in a similar case, WKU released nearly a decade’s worth of sexual misconduct records this summer in response to a Herald open records request filed in 2016 and another earlier this year.

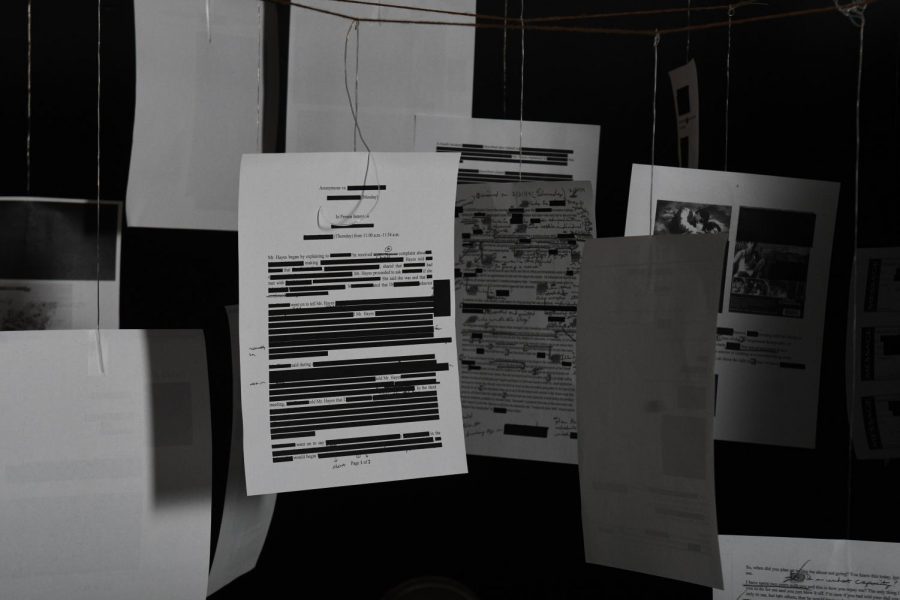

Files from both responses, a total of 39 investigations, were released but heavily redacted.

In 27 cases, covering allegations of sexual misconduct lodged against faculty or other employees from 2011 through 2020, the university concluded that the incidents did not violate WKU’s Title IX policy. Those claims involved both students and WKU employees and ranged from possible homophobic job denial to what the person felt was excessive touching.

WKU found, in nine cases, enough evidence that resulted in the resignation or retirement of faculty or staff members, effectively ending the investigation before a formal conclusion. This included a case of a male staff member threatening to place holds on a female student’s TopNet account, blocking her from registering for classes, in exchange for going on dates.

In three cases, enough evidence was found to fire or discontinue the employees.

Michael Abate, the Herald’s attorney at the Kaplan Johnson Abate & Bird law firm in Louisville, contends that the records WKU released were “seriously over-redacted.” Abate said the Herald is in the process of disputing those redactions and may ask the courts to resolve the dispute.

In the original Nov. 1, 2016, open records request, the Herald asked for all investigative records for all Title IX investigations into all sexual misconduct allegations against WKU employees in the last five years.

This request was mirrored in spring 2021 when WKU began to fulfill the original request.

WKU initially rejected the 2016 request by citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. The Herald appealed the decision to Kentucky’s attorney general, who oversees public access laws. The then Attorney General, now Governor Andy Beshear ruled WKU was in violation of the Kentucky Open Records Act and ordered WKU to turn over the documents.

Instead, WKU sued the Herald in Warren County Circuit Court in February 2017 in a case that still has not been resolved 4 1⁄2 years later.

In a similar case where the University of Kentucky refused to turn over sexual misconduct records to the Kentucky Kernel, the university student newspaper, the state Supreme Court in March ruled in favor of the publication. The court opinion said UK could not use FERPA as an “invisibility cloak” to hide all documents involved or associated with students. The federal law does indicate FERPA should be used to protect students’ educational records.

Abate said “a requester is entitled to everything in the file not specifically exempt” and WKU cannot use FERPA to redact information about employees.

The university is required to provide an index of reasons for their redactions. While WKU did provide an index, Abate disputes whether many of the redactions were permissible under the Open Records Act.

After the UK decision, WKU decided to begin turning over the 2011- 2016 records to the Herald, releasing redacted records over the next few months. In turn, the Herald made an identical request for records of such cases from 2016-2021.

With the redactions, Abate said things appear to be missing from the files. The biggest one is the names of faculty and staff accused of wrong- doing, even if the claim is not found to be a violation of university policy. Abate said there is controlling case law that entitles the public to the names and handlings of the accusations.

“In many instances, the university also redacted key substantive details of the allegations that make it difficult to know what actually happened,” Abate said. “Several files appear to

be missing documentation contained in almost all other files. And in some places the redactions are not clearly explained, so it’s impossible to know exactly what has been withheld.”

In a document outlining its reasons for redactions, WKU said it was following the ruling of the Supreme Court, federal privacy regulations and, on cases where no violations were found, a 2020 attorney general’s opinion.

For the public to have confidence in the safety of the campus community, Abate said, they must know these allegations are being handled seriously and appropriately.

“Public universities simply cannot be permitted to sweep serious allegations under the rug or quietly push policy violators out the door to other institutions where they might offend again,” Abate said. “Unfortunately, the facts that have come to light from the Herald’s reporting show that pattern of behavior is all too common among universities.”

‘In the dark’

On May 4, 2017, the Herald published “In the Dark,” an in-depth report in which former Herald staffer Nicole Ares reported on more than 1,200 pages of records obtained through public records requests to all eight public Kentucky universities.

Six of the eight universities provided records at the time, with only WKU and Kentucky State University denying the request. Ares’ story detailed violations at Northern Kentucky University, Eastern Kentucky University and Murray State University.

At the time Andrea Anderson, who was then Title IX coordinator and now WKU’s general counsel, told Ares that WKU had six investigations that resulted in violations of the university’s misconduct policy.

Title IX policy

Deborah Wilkins, WKU’s Title IX coordinator who at the time of the Herald’s 2016 request was general counsel, said Title IX discrimination includes sexual harassment and assault, domestic violence and stalking. Wilkins said this policy is not a complaint process, but is more of a services process.

When WKU’s Title IX office talks about an investigation, Wilkins said, investigators try to use neutral language. The person who filed the report is referred to as the complainant. The person accused in the report is called the respondent.

“When we get a report, the first thing we do, whether it’s an employee or a student, is [ask] what can we do to assist this person?” Wilkins said. “What services can we do to help them get on track? Get comfortable? Respond to their needs?”

These services are about bringing back the sense of safety and security the complainant had before, Wilkins said. This might include changing a student’s residence hall, prohibiting someone from entering a residence hall or getting the student from a class.

The majority of reports the Title IX office receives come from a student about another student. These reports then involve employees in the Office of Student Conduct such as Michael Crowe, director, or Melanie Evans, coordinator.

Other reports to the Title IX office involve employees, like the ones the Herald requested. The cases are handled by the Office of Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action/University ADA Services, where Joshua Hayes is director, Title IX deputy/investigator and university ADA coordinator.

Hayes declined to be interviewed.

After a complainant files a report and immediate services have been administered, Wilkins said, she is obligated under law to ask the person if they want to file a complaint and have their case formally investigated. Wilkins said they treat each report like it’s going to be a complaint, but it’s not their top priority.

“My priority is to help them first,” Wilkins said.

Once a report is made to the Title IX office against an employee, Wilkins reaches out to the complainant to speak with them about the issue.

Whether or not the complainant responds, Wilkins and Hayes begin an investigation into the complaint if it’s about an employee, a new step as of August 2020.

When Wilkins speaks with a complainant, she asks them if there were any witnesses they want the office to reach out to, which they will have the opportunity to add later. The complainant will be asked if they want an adviser to help them through the process. After the complainant has spoken with the Title IX office, Wilkins will offer them a copy of the transcript of their conversation to review and edit before officially adding it to the file.

Simultaneously, Wilkins and Hayes then reach out to the director of the area of the university where the respondent worked, assuming the complaint is not against the director, and inform them that a complaint has been filed against one of their employees. They ask the director to make sure the parties are not in close contact or sharing responsibilities.

Next, they interview the respond- ent against whom the report was filed to hear their version of events. They too are offered an adviser and asked for their list of witnesses. The respondent may say the opposite of what the student says and they are also allowed to review their statement.

If there are videos, messages or emails that can be provided as evidence to the case, Wilkins said she and Hayes would also review those as a part of this process.

Hayes and Wilkins then start talking to witnesses and having them review their statements for the investigation. This can take varying lengths of time, depending on the size of the department, how many witnesses there are and how fast they respond.

Once the file is completed, it is shared with the complainant and respondent. They may have nothing to add to it.

“Then Josh and I will determine, do we think there’s a likelihood the policy has been violated?” Wilkins said. “Is there enough here to have a hearing?” Another change since August 2020 is that if there is an employee involved in a complaint, there will be a hearing with an outside officer from the state Council on Postsecondary Education unless the allegation turns out to be entirely without foundation. Wilkins said an example would be if there was an allegation of an incident that happened on campus and the accused employee was proven to be in California at the time.

During this process, an employee respondent can decide to resign or retire. If they do, then the investigation stops and that will be noted in the record. Wilkins said this stops with retirement or resignation because the university essentially loses jurisdiction.

If the hearing officer decides the respondent has violated Title IX policy, the office issues a notice. Then the respondent’s department head and the vice president of the division where the respondent works have 10 days to decide how they’re going to address it and inform WKU’s Title IX office, another new step as of August 2020.

WKU requires any employee who hears of sexual misconduct to report it to the Title IX office, even if it doesn’t involve them or their work, but does not expect the person making such a report to verify that the incident actually occurred.

“Basically, what I’m hammering on them is you don’t have to investigate, you don’t have to determine if it’s true,” Wilkins said. “Just call us and we’ll determine if it’s true and you can go on your way.”

Title IX changes

On Aug. 14, 2020, new federal Title IX regulations took effect.

“In my mind, the biggest change was the fact that if it involves an employee, there is a hearing,” Wilkins said.

This means that with every Title IX report that comes in involving an employee, the office has to do a full investigation.

“If there’s evidence to show that it’s more likely than not that a violation occurred, we will have a hearing,” Wilkins said.

Reports that only involve students can end or be resolved without a hearing.

For each report involving an employee, the hearing officer for the case is a neutral person from the state Council on Postsecondary Education. This hearing officer will hear from the complainant, respondent, any witness and the investigators before deciding if the policy or policies in question were violated. Before August 2020, those matters were handled within the university.

After the hearing officer makes a decision, the complainant or the respondent can appeal it and then a new hearing officer will make a new decision. However, no one else can appeal the decision. The respondent’s supervisor is not allowed to disagree and ignore it.

Wilkins said WKU has not, as of yet, had an occasion that would need a hearing officer from the CPE.

“The other thing that was part of the changes in federal law was that if you’re an employee and you have an investigation pending against you, you can’t resign or retire,” Wilkins said. “No one can prevent an individual from quitting a job, but the new regulations require us to note on that employee’s permanent records, employment records that they resigned or retired under an investigation.”

Before, there was no requirement for a former employer to disclose if the person under consideration for a job had left their previous position under a Title IX investigation. Potential new employers only knew of that if they asked.

It is now required to disclose if someone left under investigation in a job recommendation. Wilkins said the people hiring the respondent do have to reach out to the university and ask about them, and if they do, their former supervisor must tell them about the investigation. If a student leaves under an investigation, that is also noted on their permanent record.

Wilkins said if a student or an employee leaves the university, WKU loses jurisdiction over the process.

“We can’t force people who are no longer associated with us to come back and go through the processes,” Wilkins said.

From the case files the Herald received through open records requests, several of the cases appear to have ended because the employee left the university.

Amid the Title IX policy changes, there is also now a requirement for the supervisors of the employee who is found to violate the policy to report back to the Title IX office in writing their decision on what to do within 10 days.

“When you’re forced to look at objective decision making and make your own decision and sign your name to it, it makes it a little harder to excuse bad behavior,” Wilkins said.

The decision about consequences for the respondent goes to the super- visor and the vice president of their division because they are responsible for the people who report to them. Wilkins said they should be a part of this process.

“It holds them accountable in two ways — one, accountable to address the bad behavior that’s already happened, and it also makes them aware that they’re also going to be held accountable for future bad behavior,” Wilkins said.

She said that in the past, supervisors have asked Title IX what they thought about the situation and asked for advice.

At the WKU level, Wilkins said some minor change to the Title IX policy should be going to the president’s cabinet this week. This includes adding prevention of LGBTQ discrimination.

39 Files – the breakdown

Out of 39 cases the Herald received, five files had male complainants, 31 files had female complainants, two files had complainants from two genders and one case file’s complainant gender could not be determined. There were 36 case files with male respondents and 3 case files with female respondents.

The records show that the university found violations of the Title IX policy in 12 of the 39 cases WKU investigated. WKU did not redact the names

of faculty or staff members who were found to have violated the policy in those instances.

The files varied in size ranging from 15 pages to 293, totaling to 5,884 pages, varying based on the number of witnesses interviewed, evidence and who handled the case.

“The only difference, and this is very innocent, is [that] you got two different people in charge,” Wilkins said. “Joshua Hayes is very detail oriented and he documents everything and keeps everything so that’s why you’ll see a whole lot more in his files.”

Before June 30, 2015, the Director of the Office of Equal Employment Opportunity and the Title IX coordinator was Huda Melky, who retired.

The variance in the case files extends to how much is redacted. One example is in Case Q from the 2016 open records request, where words from WKU’s own Discrimination and Harassment Policy from April 1, 2013, were redacted from the file the university turned over to the Herald.

“This policy does not supersede or replace any grievance or complaint procedures contained in the [redacted] Handbook,” the case file stated.

There is another one word redaction in the “Members of the University Committee” subsection and several one word redactions in the “Consensual Relationship” subsection.

“It is impossible to understand why the university would redact part of a university policy that is otherwise publicly available,” Abate said. “There is no good-faith basis for doing so.”

Cases to note

Within the records the Herald received, most of the names of those faculty and staff investigated were redacted. However, 12 records where WKU found violations occurred or likely occurred did include the employee names.

One of the 39 cases, Case S from the Herald’s 2021 open records request, is a student employee vs. student employee Title VII and Title IX report and investigation. The events on this file revolve around two former student employees at the Herald during the 2019-20 year.

The files consist of emails and handwritten notes and do not have any formal memos stating whether or not the respondent violated any policies. Investigators recommended that the person accused complete two training sessions, and that person was not hired back at the Herald.

The Herald is disclosing this information about this case to hold itself to the same standard as WKU.

Cases with violations

Kenneth Johnson Case A

Kenneth Johnson, former assistant director of student activities, was investigated for violating the sexual misconduct policy in 2014 after a student filed a complaint of sexual harassment.

In the complaint, the student said on several occasions that Johnson threatened to place a hold on her TopNet account to prevent her from registering for classes if she did not stop by his office to visit him and have dinner with him. The student said she initially thought Johnson had the authority to place a hold on her account, but later found out that he could not do that. Before learning that, she agreed to have dinner with him.

“I had knots in my stomach. It bothered me how he used his position as a form of manipulation,” the student stated in the report.

The student said she had seen other students experience similar occurrences with Johnson.

In the investigation, WKU interviewed 24 witnesses. Some denied experiencing or witnessing any form of harassment.

Other witnesses mentioned trying to avoid Johnson, hearing rumors about him dating or having “flings” with female students, saying Johnson was “close” with female students.

One witness said, “It was a running joke that if you wanted to get ahead, you would sleep with Kenneth.”

Another witness said Johnson would take her to lunch and dinner, one-on-one, approximately three times per week. He would pick her up at her home, and would play “romantic” music. Johnson had purchased alcohol for both of them at dinners.

Based on the findings of the investigation, Johnson violated WKU’s Standards of Conduct policy and Discrimination and Harassment policy in addition to Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972. The file does not indicate if Johnson retired or resigned, but he is no longer employed at WKU.

Other violations found

Case B, from the 2016 request, involved Colleen Donovan, an academic readiness instructor, who WKU found had violated the university’s discrimination and harassment policy, according to the investigation in May 2014. A female student in her class filed a complaint because she notified Donovan that she would need to miss a few classes due to medical reasons. Donovan told her that she does not accept medical excuses, that no one could help her, and that according to her syllabus if a student is absent from three classes the student’s grade drops to the next lower grade. Donovan was no longer employed at the university after May 2014.

Case C, from the 2016 open records request, involved Timothy Mullin, former director of the Kentucky Museum and Library, who was investigated for violating the sexual misconduct policy and gender based discrimination after he made sexual comments towards others. The records include complaints that surfaced of him sexually harassing male students and belittling and berating the female employees he supervised. Mullin died in 2020.

Case D, from the 2016 request, involved Steve Briggs, assistant director of Housing and Residence Life, who WKU found had violated the university’s sexual misconduct policy after an informal complaint filed by a female student on Nov. 12, 2014. A university employee complained that Briggs rubbed her arm and poked her arm in the hallway, then approached her from behind and rested his hands on her hips. When she moved away, Briggs said, “It’s just me.” On Sep. 9, 2015, Briggs submitted a letter of resignation.

Case E, from the 2021 open records request, involved Jim Hills, an events associate for WKU, who WKU terminated on June 4, 2019, after the Title IX investigation regarding him concluded. WKU found that Hills would discuss inappropriate sexual matters with student workers. According to the document, Hills would compliment body parts, talk about women and stare in an uncomfortable way while setting up events with student workers, based on witness statements.

Case F, from the 2021 request, involved Keith Clark, a senior academic advisor, who WKU found had violated the sexual misconduct policy in 2018 after a complaint was filed on March 18. Clark had been sending Facebook messages to a University of Louisville employee from March 13-17. He sent the employee a video of him “spanking/paddling” himself. He also sent her a photo of him bent over a stool, wearing an apron, spanking his bare bottom with a paddle. Clark resigned from the university.

Case F, from the 2016 request, follows an investigation against Michael Kallstrom, a professor in the music department. On Sept. 3, 2015, WKU began looking into a report from an- other faculty member who expressed concern about Kallstrom’s interactions with a student. The student said she went with a friend to see Kallstrom, and while the friend turned to answer a phone call, Kallstrom put his hand on her thigh. The university found that Kallstrom violated the university policy. He retired shortly after.

Case G, from the 2021 records request, investigated a complaint that was received on Jan. 31, 2018, about Bryan Carson, coordinator of research instruction, grants and assessment. The complaint was in response to recurring incidents after a complaint against Carson in 2011. Based on the record, Carson made female employees and students feel unsafe around him. On Feb. 28, 2018, Carson resigned and was listed as ineligible for rehire at WKU. He then went to work at Missouri Valley College.

Case A, from the 2021 request, investigated Ron Mitchell, an associate professor at WKU. On Oct. 3, 2017, Lisa Schneider, assistant to Athletics Director Todd Stewart, called Joshua Hayes to tell him about an issue with Mitchell and a female student. According to the documents WKU provided, Mitchell invited the student to his house for lunch. He picked her up from Diddle Arena, took her to a “big house,” went to a restaurant and then went to a different house. At the second house, Mitchell massaged her legs, back and feet, and continuously told her to release. During the massage, he told her that her clothes were dirty and that she needed to change into clothes he had for her. She said no. The student said no to the massage when he reached her upper thigh. She said Mitchell unfastened her bra, according to the documents, even though she said no. In an in-person conversation with Schneider and the student, Hayes asked how the student remained calm, she typed the answer on her phone: “I felt sick. But I was scared so I could not say no.” Mitchell resigned from the university on Oct. 18, 2017.

Case C, from the 2021 request, investigated a complaint filed by an anonymous employee against Tim Boyer, access control locksmith, to the Title IX office in November 2020. On Nov. 17 at 10:10 am, there was an incident that was recorded by surveillance mentioned in the emails. “While [redacted] was searching the key file storage, Tim rolled across the workshop floor in his office chair and positioned himself behind her while she was seated on the roller stool. The shop video shows Tim straddled within inches of her back and torso leaning over her shoulder. [Redact- ed] said she could feel his upper body/chest touching her back. The encounter lasted approximately one minute.” In an email from Deborah Wilkins, she said there were three issues she thought were important to the case: there is video evidence regarding the complaint, Boyer is an “at will” employee so he can be terminated at any point, and Boyer had no meaningful excuse for his behavior in the video. WKU found that Boyer violated the WKU sex and gender-based harassment, discrimination and retaliation policy. He was immediately terminated.

Case D, from the 2021 request, dealt with Muhammad Sajjad, visiting assistant professor in physics and astronomy, who was “discontinued” and ineligible for rehire because a violation of policy was found. According to the records, the student told Hayes that she was standing by Sajjad’s desk in the classroom behind the computer, and Sajjad was standing beside her, and his genitals were hitting her outer thigh. She clarified that Sajjad rubbed his genitals against her thigh in a side to side movement. Hayes asked how long Sajjad rubbed himself against her. She said Sajjad rubbed himself against her the entire time she was alphabetizing the exams, which took about five minutes.

Case E, from the 2016 request, investigated a complaint that was filed against Brent Fisk, visual and performing arts library senior circulation assistant. According to the complaint, Fisk left his Pinterest ac-count open showing naked — “specifically topless” — women on March 25, 2014. The incident was considered inappropriate use of WKU technology. Co-workers said they felt uncomfortable around him since they were the same age and “type” of women in the images Fisk had been looking at. From the documents provided, it is not clear whether Fisk resigned or was terminated from the university, but he did not continue to work at WKU after 2015.

Cases with no violations

The majority of the cases the Herald received were reports where no violation against university policies were determined. Cases K and T from the 2021 open records request had enough detail to be described thoroughly.

Case K

On May 2, 2018, a student reached out to Peggy Crowe, director of the Counseling Center, about an email he had received from his Interdisciplinary Studies instructor that caused concern.

The lead up to this email had been a conversation about planning a trip with the instructor and other students that the complainant would no longer be able to attend. Upon discovering the student could no longer attend the trip, the respondent sent an emotional response telling the complainant not to show up to the next class meeting he was supposed to attend as a peer mentor.

“I have a few days to deal with my loss and I definitely do not want to fall apart in front of the class,” the response from the employee in the file stated.

From this interaction, the report and ensuing investigation revealed a long-time mentor-mentee relationship between the complainant and respondent. Instances involving heavily emotional conversations on the part of the respondent, multiple trips to conferences, a specific conversation involving bowties and Chippendale dancers and appearing in the complainant’s personal life were discussed in the investigation.

As the final email included in the file, the documents state that on Aug. 7, 2018, Hayes spoke to the respondent where he shared his findings and reminded him of three previously discussed points — encouraging the respondent to receive counseling, “discouraging him from personal travel with students” and having a separate room when traveling with students for work. WKU did not find a violation.

Case T

On Sept. 17, 2018, a student reported a theater professor teaching Acting for the Camera whose name was redacted. The professor told the student, while she was undressed

for a scene, that she could receive an “easy A.” Other students urged her to report what happened due to a similar incident that occurred prior.

In an interview with Hayes, the professor denied ever making the comment.

The student was cast in a script written in a screenwriting class that one witness described as “borderline pornographic.” The student emailed the professor stating she was un- comfortable, to which the professor responded that they needed to talk further and that his “hands were tied.”

The student told a dance instructor who encouraged her to report the incident and said it was “unacceptable.”

During the investigation, 15 witnesses were interviewed. One witness said that removing clothing for the “fake porn” scene was optional. Several witnesses mentioned not having any concerns about the professor, one referred to him as a “father figure.” Other witnesses mentioned not feeling comfortable around him.

A result of the investigation was a two-week period for students to decide if they are comfortable with their assigned script being added to the course syllabus. The professor was told to refrain from joking with students unless they have a “mutual cohesive relationship.”

No violation of Title IX was found during this investigation. The investigation ended on Dec. 13, 2018.

Herald staffers Michael J. Collins, Anna Leachman, Megan Fisher, Jacob Latimer, Shane Stryker, Jake Moore and Leo Bertucci contributed to this story.

Digital News Editor Debra Murray can be reached at debra.murray940@topper.wku.edu. Follow her on Twitter @debramurrayy

Editor-in-Chief Lily Burris can be reached at lily.burris203@topper. wku.edu. Follow her on Twitter @lily_burris.