Math department head calculates campus COVID-19 death rate

August 25, 2020

As colleges across America reopen during the global pandemic, WKU Department of Mathematics Head Bruce Kessler decided to look at the reality of the numbers. What he found was alarming.

When Kessler attended a meeting held by WKU faculty earlier this summer that centered around the newly-configured plans for the Fall 2020 semester, he was shocked to hear that nobody, not even the faculty of the Environmental Health and Safety department, had asked the question that seems to loom over each conversation about the reopening of WKU: How long can Western stay open before the fatality of a WKU faculty member or student?

Kessler was met with blank stares and pursed lips when he posed this question at the meeting.

“The answer I got made it very clear that nobody had actually tried to calculate it,” said Kessler. “They told me there were too many variables to account for to properly calculate an answer to my question.”

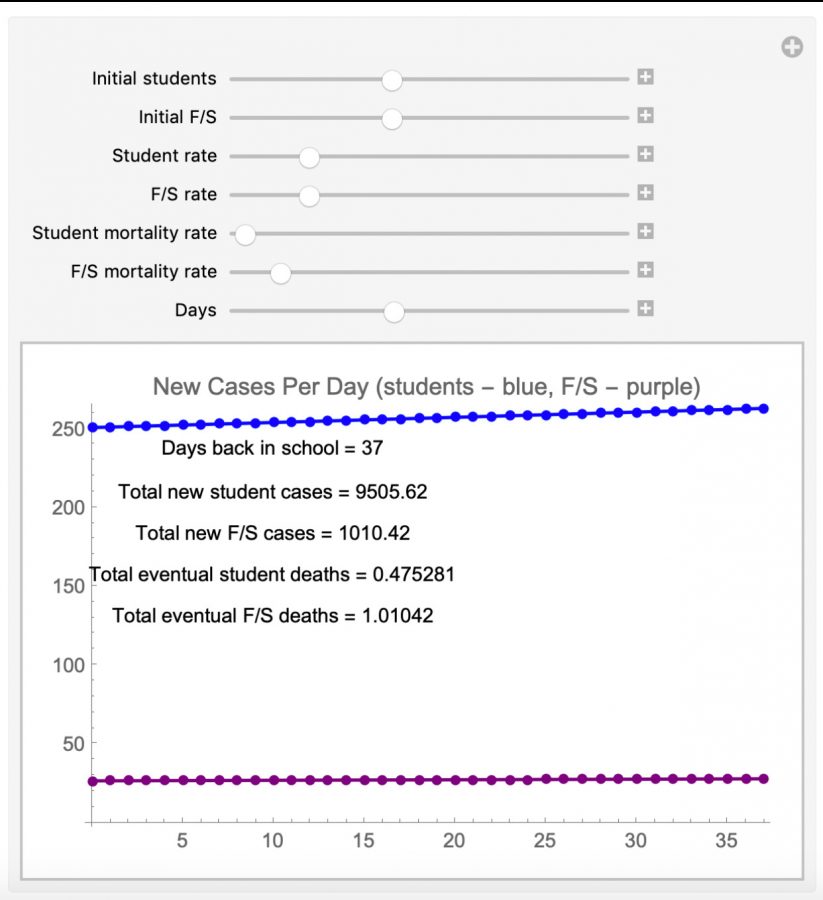

As a math modeler himself, Kessler said he knew these were “crap.” He immediately took matters into his own hands and created a rudimentary exponential model measuring the time it would take for a faculty member or student to lose their life to COVID-19 based on information he gathered mainly from WKU’s Human Resources department, alongside his own research.

He first looked at the number of students planning to take in-person classes this semester and the number of faculty members planning to teach in-person classes this semester.

Kessler has also been tracking the rate of increase of new cases in the state of Kentucky since mid-April, paying close attention to the hot spots within the state, Warren County being one of them. Finally, he did research regarding the statistical probability of death due to COVID-19 based on age and pre-existing medical conditions, although it was impossible for him to work specific variables into his model without knowing the exact ages and medical records of each student and faculty member.

He estimated that student ages range mostly from 17 to 23, and faculty and staff members have a much wider age range. With this information, he was able to predict how quickly it would take enough students and faculty to become infected before someone died.

He crafted two separate models, one for the student population and one for the faculty population, both in exponential form, both accounting for basic variables. For faculty and staff members, 1,000 people would have to become infected before a faculty and staff member died. For students, 20,000 would need to become infected before a student died.

This model is good news for students: WKU’s current number of students returning to campus is estimated at 12,100, which is almost 8,000 less than the number of students that would need to be infected before a fatality. This number of positive cases is impossible to reach. However, the numbers pertaining to faculty and staff are much more alarming. His model shows that it will take 29 days for 1,000 members of the WKU faculty and staff to test positive for COVID-19 if WKU reopens as planned.

However, Kessler was persistent in his faith that the university will not allow positive cases to climb that high before drastically changing the way campus operates.

“The purpose of these models is to see the ramifications of our current policy decisions,” said Kessler. “I’m not necessarily saying that this is going to happen, because changes will come. But it is a real possibility.”

This terrifying reality is the reason Kessler crafted an exponential model instead of the common “bell curve” model.

Kessler argued that policy decisions should be made on the front end of the curve when it comes to a deadly virus, lessening the number of people this virus will affect throughout the WKU community. This time is about making changes as soon as positive cases begin to rapidly increase, which is exactly the time period that an exponential model shows.

“If we do not adjust while things are starting to shoot upwards, it will start looking a lot more exponential on my model,” said Kessler.

Kessler also urged people to keep in mind that his model is a conservative estimate. He has no way of accounting for each individual student or faculty member that has a pre-existing medical condition, putting them at a higher risk of death from COVID-19, so everyone must look at this model as a simple baseline for how quickly there could be a fatality.

Unfortunately, a fatality may occur much sooner than Kessler can calculate, due to outside factors he is unable to incorporate in his model.

While Kessler’s model did focus on mortality rates, he wants to make clear that death is not the only negative outcome from COVID-19 spreading throughout campus. Coronavirus can have long-term health effects, including internal organ damage and loss of or damage to senses.

Kessler finally stressed that WKU community members need to also consider these factors when they view his model; death cannot be the only outcome that stops WKU from opening its doors again.

This seemingly never-ending nightmare does have a light at the end of the tunnel. WKU does indeed have time to act before this virus gets completely out of hand. What Kessler is hoping his model will do is open people’s eyes to the true danger that could permeate campus.

Kessler is continually faithful that WKU will act accordingly if his model is proven to be true, but he has no intention of terrifying or guilting the community with his data. In fact, he understands that faculty and students are only trying to make the best of a horrible situation.

“I think people are just craving normalcy,” said Kessler. “But right now, going back is just not a good idea. Unfortunately, that is the reality that we have to face as a community.”

Liza Rash can be reached at 270- 745-6291 and liza.rash282@topper. wku.edu. Follow Liza on social media at @l1za_.