Black History Month: Time to recognize racial bias and seek equality

February 18, 2020

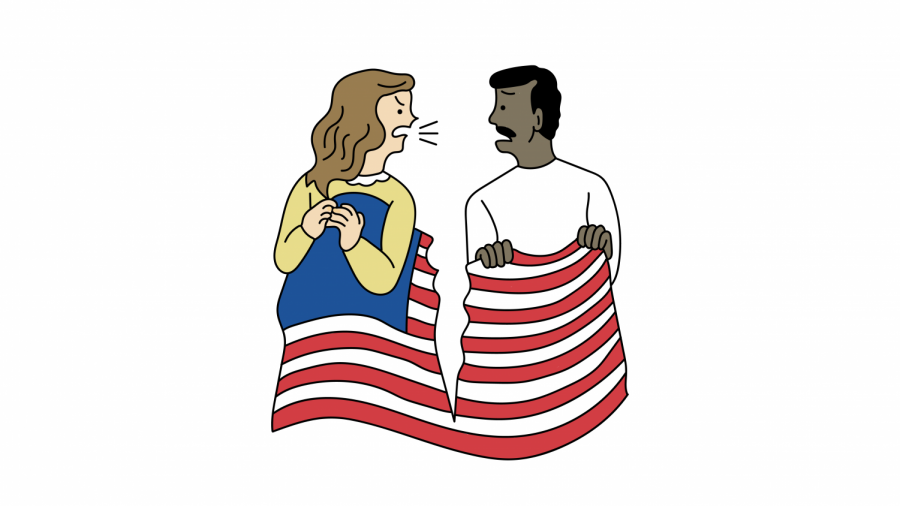

Issue: Many Americans see our country as a place of equality for all people, but sometimes the reality is more complicated.

Stance: Considering the long history of inequality in America, we have progressed substantially to a place of unparalleled opportunity. However, Black History Month is a time to not only recognize African American achievements and struggles of the past but also see where the gaps in equality have yet to be closed.

Without a doubt, America has come a long way since the evils of slavery, abolished in 1865. But racial segregation still exists in America’s public education system, and racial biases undoubtedly linger, affecting African Americans in the U.S. criminal justice and healthcare systems.

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and black Americans are 13 times more likely to be imprisoned for drug charges despite the fact that the difference in usage rate of illicit substances between black and white people is within 1%, according to a study from the Annual Review of Public Health Journal.

Additionally, black men serve roughly 19% longer sentences for the same crimes committed by white men, according to a report from the United States Sentencing Commission.

Bias also seeps into the healthcare industry, where black people and other minorities face less personalized care, less access to transplants and more misdiagnoses. This is not because doctors and other healthcare professionals are racist. Several studies have shown their levels of implicit, also known as unconscious, bias to be the same as the general population.

It is important that we recognize our racial biases and truly seek to view each person, like Dr. King once suggested, not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

We asked several history professors what the significance of Black History Month is in 2020, and their responses can be seen below. But first, an excerpt from WKU professor Andrew Rosa’s Jan. 30 speech explains the origins of Black History Month:

“The lack of public awareness about the African American past led [Charles G.] Woodson to create ‘Negro History Week’ in 1926, to ensure, in the very least, that young people gained exposure to African American history, a central organizing theme of his now classic ‘The Miseducation of the Negro’(1933), which still remains in print. Woodson purposefully selected the second week of February in order to acknowledge the births of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, believing this would keep their legacies on the side of African American freedom alive in the memory of a forgetful nation.”

Rosa said that Woodson’s idea was also influenced by larger socio-political events shaping life in the 1920s, such as the rise of the Harlem Renaissance with writers like Langston Hughes, Ann Petry and Claude McKay. Musicians like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington influenced American culture forever and captured “the rhythms of the tens of thousands of southern blacks streaming into cities like Chicago, New York, and Detroit …”

“Ultimately, Woodson believed Negro History Week—which became Black History Month in 1976 — could be an effective vehicle for bringing about meaningful racial transformation in the country,” Rosa said.

The question facing us today, Rosa said, is whether or not Black History Month is still as relevant as it was in Woodson’s day.

“Is it simply a time when the media pushes its African American content, or does it remain, as in Woodson’s day, a useful concept in pursuit of social justice goals yet achieved? I would like to suggest that Woodson’s vision remains relevant as a source of hope surely needed in this world and as a reminder to us of not just the distance traveled, but of how far there is left to go,” Rosa said.

Assistant professor Kate Brown

“African American history reminds us of the power wielded by those who demand equality and equity — but also how far we have to go before we realize a truly equal and equitable America.”

Professor Emeritus John Hardin

“African American history is not limited to one month or one day. African Americans have been in the Western Hemisphere since the 1500s and in what has become the United States since 1619. Yet there are those persons today who strongly believe black Americans have not contributed anything of substance to the United States at any time. Without the efforts of Dr. Carter G. Woodson and others who started Negro History Week in 1926, these erroneous beliefs would have become entrenched and remain in place to sustain racial hostilities. Dr. Woodson and others of similar views formed an organization known today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (There is a WKU chapter of ASALH). It is needed now more than ever to counteract the ignorance inherent in racism. Black History Month is only one part of the struggle. The WKU African American Studies program and history department have courses to counteract ignorance as well. All students are always welcome in these classes.”

Associate professor Tamara Van Dyken

“When we have state legislatures passing days in honor of Ku Klux Klan leaders, police shooting and killing African Americans on their own property, and university students and administrators who think singing the n-word is not a problem, it seems clear that knowledge of African American history and understanding the African American experience in the United States is not only significant for all Americans in 2020 — it is necessary.”

Opinion Editor Jake Dressman can be reached at [email protected].

![Students cheer for Senator at Large Jaden Marshall after being announced as the Intercultural Student Engagement Center Senator for the 24th Senate on Wednesday, April 17 in the Senate Chamber in DSU. Ive done everything in my power, Ive said it 100 times, to be for the students, Marshall said. So, not only to win, but to hear that reaction for me by the other students is just something that shows people actually care about me [and] really support me.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/jadenmarshall-1200x844.jpg)