Unpacking the spectacle of the Iowa caucuses

February 4, 2016

Feb. 1 marked the somewhat concrete, semiofficial beginning of the 2016 election that had been underway since 2012, and the 2020 election is sure to take off in the coming months.

All eyes turned to Iowa on Monday as the caucuses took place. The Associated Press reported that Republican Texas senator Ted Cruz won with eight delegates and 27.6 percent of the vote. The Democratic caucus came in tighter as former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton came in with 23 delegates and 49.9 percent of the vote.

Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, Democrat, polled in with 21 delegates and 49.6 percent of the vote. Sanders called the results a “virtual tie” with Clinton in his speech Monday night.

Now if you haven’t heard anything about Iowa since 2012, it’s probably because the state’s boom in popularity and reporting coverage comes every four years in sync with approaching presidential elections.

First, what exactly is a caucus? Does it differ from a primary? Why is Iowa’s so early, and more to the point, why Iowa? One possible answer to the latter question is that at some point in our country’s history, we decided to pin a map of the United States on a wall, put on a blindfold, spin around a few times and then throw a dart to see where it landed.

Understanding the procedures and intricacies of the Iowa caucuses can be a bit hectic, and we’re not even the ones voting in it. To put into perspective what has recently happened in Iowa, let’s start with the question “What is a caucus?”

Give or take some technicalities, the Iowa caucuses are just like any other election, but instead of simple yeas or nays — raising a hand to vote for your eighth-grade class president — this election is separated into political parties and takes place across Iowa’s 1,681 precincts.

The caucuses are really the first step in a four-step process that will choose the state’s delegates to each political party’s national convention, at which time the presidential nominee is selected, according to The Guardian.

Think of the caucuses as if you were baking a cake. You have to start with ingredients to build a foundation that later becomes the cake. For comparison’s sake, we’ll say the caucuses are the cake mix; you still need to complete a few steps before you put the foundation in the oven and pull out a scrumptious presidential nominee.

When you add political parties, everything becomes a little more confusing. This is because Republicans and Democrats caucus differently, and only registered members to those two parties are able to participate.

According to CNN Politics, the Republican caucuses are a fairly straightforward process. Each of the campaigns has the opportunity to have a representative make one last pitch before a secret ballot is taken. Votes are then collected, tallied and sent off.

Caucusing for Democrats is a more complex process. Scott Lasley, political science professor, said instead of Democrats having a secret ballot they immediately divide you based on your preferred candidate.

“The Hillary supporters went to the Hillary corner, the Bernie Sanders went to theirs, if there was an O’Malley supporter they went to theirs,” Lasley said.

Lasley said based on those results any candidate which does not meet a 15 percent threshold at that precinct is not considered viable and they must join another candidate, or persuade people to join them.

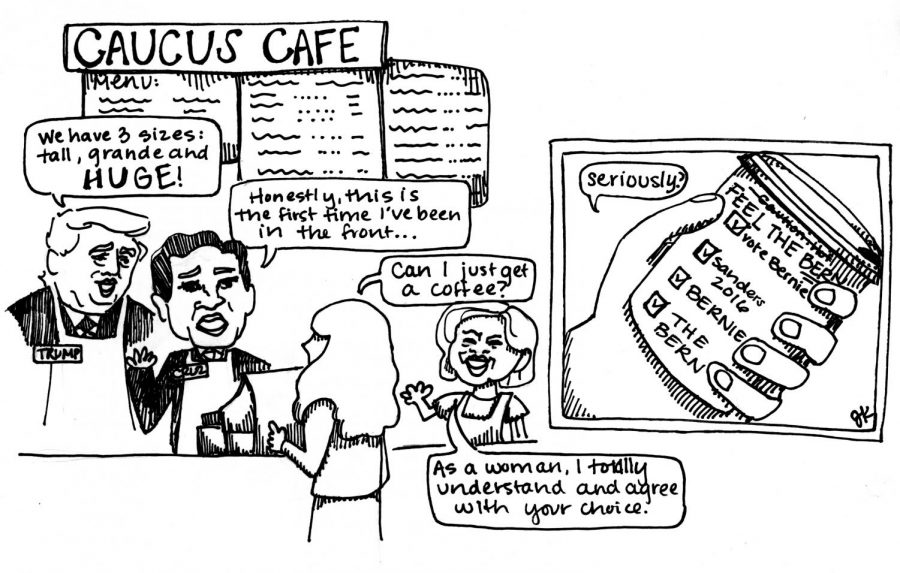

To look at the Democratic caucus in a different light, imagine if you were to walk into Starbucks at Downing Student Union and the barista immediately asks you for your order all the while assuming you’ve been keeping up with your preferred coffee’s foreign and domestic policies for the past six months.

Say you sided with Starbucks’ caramel macchiato because you agree with its stances on gun control and higher education reform. You would then go stand with other people who side with caramel macchiato.

However, if the number of people at your precinct who support caramel macchiato does not meet 15 percent then you either have to persuade others to side with Caramel Macchiato or go to another group, such as cinnamon dolce latte or white chocolate mocha.

It’s in this regard that Lasley finds the process for Democrats in particular as “very unique and interesting.”

Saundra Ardrey, associate professor and political science department head, said the Iowa caucuses are important simply because they’re first.

Otherwise, Ardrey said, other caucuses don’t receive that much attention because of the processes involved with them. Ardrey said many of the people who turn out to caucus are the extremes of both parties and not as many who are more middle of the road.

Ardrey also said Iowa is not a good barometer of what’s going to happen as far as the who’s nominated or who will win the general election.

“98 percent of the population [in Iowa] is white and is overwhelmingly evangelical,” Ardrey said. “Candidates are not going to have that situation as they approach other states and other primaries, so we have to be careful of these causes as well as these primaries because a lot of times they’re not indicative of the general population.”

Ardrey said the caucuses make for newspaper hype and giving candidates momentum as they move forward. Ardrey used senator Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, as an example. Rubio came in third in Iowa, but he was thought to have won because expectations for him were low.

Ardrey’s warning of being cautious about future caucuses and primaries comes with appropriate timing; they seem to be the only thing candidates and news anchors can talk about. In reality, they can be more superficial.

“A lot of folks say it’s just a beauty contest,” Ardrey said.

The print version of this story had information which was missing. The full story has been updated in full online. The Herald regrets the error.

![Megan Inman of Tennessee cries after embracing Drag performer and transgender advocate Jasmine St. James at the 9th Annual WKU Housing and Residence Life Drag Show at Knicely Conference Center on April 4, 2024. “[The community] was so warm and welcoming when I came out, if it wasn’t for the queens I wouldn’t be here,” Inman said.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/smith_von_drag_3-600x419.jpg)