Folklorist and WKU alumna hosts discussion about COVID-19

October 1, 2021

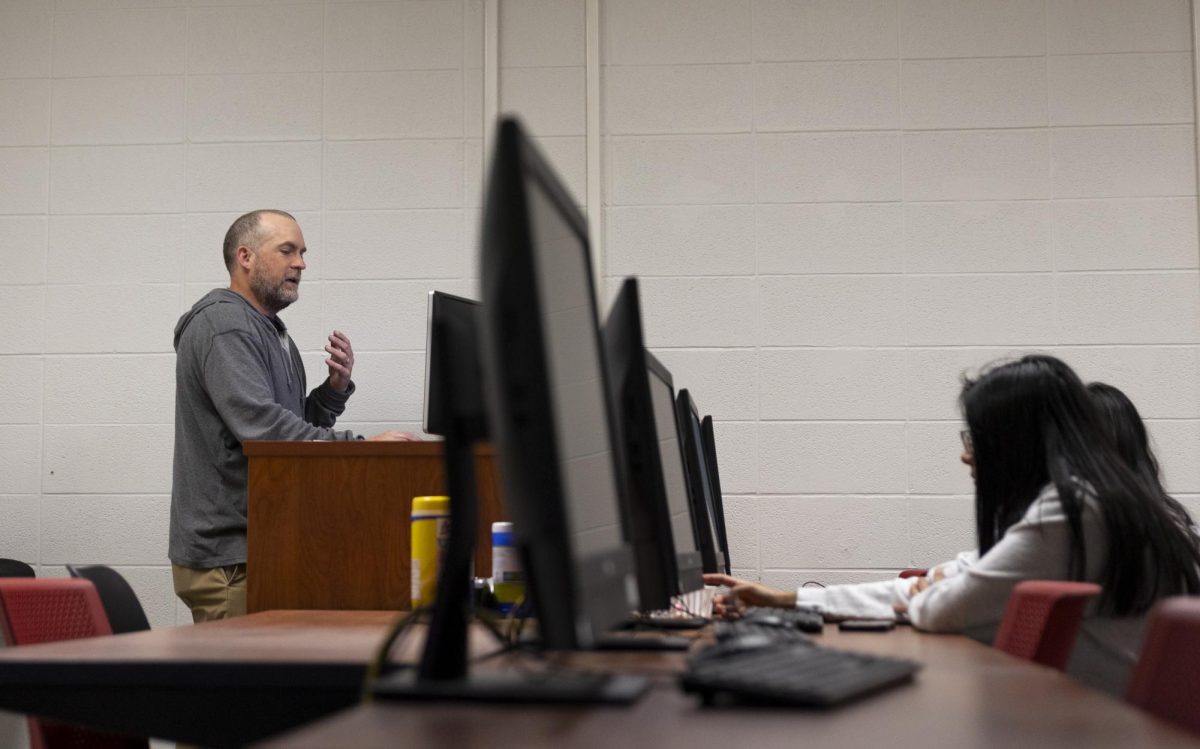

WKU alumna and folklorist Andrea Kitta held a virtual discussion titled “Communicating about COVID: understanding how folklore affects medical decision making and what to do about it” on Thursday, Sept. 30.

Kitta is a professor of English at East Carolina University and has been studying the basis of this topic since 2003.

Kitta explained how rumor, legend and misinformation all affect our medical decision-making and how best to communicate with others about the COVID-19 vaccine. She focused on communication with those that are vaccine hesitant and provided three steps to talk with these people about why they feel this way.

Folklore belongs to everyone, it’s not just for a certain group or age or race or profession or socioeconomic group or religion. And it’s not just a thing to dismiss or correct. Folklore isn’t necessarily incorrect, it’s just informal.

— Andrea Kitta

“A lot of the reason is also medical distrust, but being a folklorist takes me out of that realm. I’m connected to medicine and science but I’m not a part of it,” Kitta said. “So some people feel I’m more trustworthy or that they can talk to me because I’m not in medicine directly, so that’s part of the reason I like to talk about it as well.”

Kitta also explained why folklore connects to this medical and social mistrust around the vaccine so easily.

“There’s so many reasons why we tell these stories and one of those things is to talk about our concerns, especially when we’re unsure about information,” Kitta said. “We also might pass on stories that are hard to believe so even if we don’t fully believe them, there is an element of believability about them.”

This connection between folklore and medical topics like COVID-19 may be hard to see for some.. Many think that folklore is just a collection of made-up stories, but Kitta wants to show her field in a different light.

“Folklore belongs to everyone, it’s not just for a certain group or age or race or profession or socioeconomic group or religion,” Kitta said. “And it’s not just a thing to dismiss or correct. Folklore isn’t necessarily incorrect, it’s just informal.”

Kitta provided three main steps to begin communicating with others that are vaccine hesitant. Her first step was to not pressure the person you’re speaking to and try to understand their fears. Next, after they begin to feel more comfortable, begin to ask peripheral questions that focus on the edges of those beliefs. Finally, she suggests following up with research articles a few days later so that vaccines can be explained in someone else’s words and not just your own.

“If you start to do this, it does begin to work over time with repetition,” Kitta said. “Their motivation to change is enhanced if there is a gentle process of negotiation in which they, not you, articulate the benefits rather than costs involved. Let them defend their beliefs without antagonizing them.”

News reporter Alexandria Anderson can be reached at [email protected].

![Students cheer for Senator at Large Jaden Marshall after being announced as the Intercultural Student Engagement Center Senator for the 24th Senate on Wednesday, April 17 in the Senate Chamber in DSU. Ive done everything in my power, Ive said it 100 times, to be for the students, Marshall said. So, not only to win, but to hear that reaction for me by the other students is just something that shows people actually care about me [and] really support me.](https://wkuherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/jadenmarshall-600x422.jpg)